“In times of climate crisis, the future is a territory to defend.”

Guest CSW66 blog from Mitzy Violeta, activist in Futuros Indígenas (Indigenous Futures). Original en Español debajo.

As women defenders of the land, it’s very clear to us the causes of this climate crisis and ecological emergency.

It is the logic of extractivism – where capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy come together. It doesn’t only damage our Earth, but also sows violence and division across our communities. It affects our health, our ways of life and our relationship with nature. Those of us who live with the consequences in our lands cannot only speak of ‘climate change’. We need to name the urgency in which they are destroying our land, and the way in which we name the problem can help make it more visible.

One of the tasks that we have now is to continue sowing hope. By telling stories of our peoples, and our own life histories, is to show the true consequences of the climate crisis. Which is a crisis of life in general - and one that should be understood from the experiences of the land. Because, this climate crisis is a symptom of a colonial, capitalist and patriarchal system that reproduces extreme inequality and injustice. Us women, we live with the consequences of this crisis, but we also very clearly see the causes, the logic and practice of extractivism.

Why am I an activist?

When it seemed that everything was lost, we decided to organise ourselves. I am Mitzy Violeta, Mixtecan from San Sebastian Tecomaxthahuaca in Mexico in Central America and Abya Yala. Since I was small, I was uncomfortable with the injustices that I was aware of. Although I didn’t know much about their origins, this uncomfortableness is what led me to begin weaving movements with other women.

First, from the city we organised to confront racism and have a safe space with other rural and migrant women. Afterwards, and through this process, I also recognised the importance of naming myself in relation to my community and my ancestral indigenous roots. I also knew then I needed to take action to change these situations – that I myself had lived through, so I joined up with different groups and collectives of indigenous women.

More recently, I found that the injustices that we face as indigenous women are the same that traverse the land. And, the biggest motivation for me to mobilise in movements and articulate these fights was the thought: What alternatives are possible, and what society could we build?

"I found that the injustices that we face as indigenous women are the same that traverse the land."

Alternatives that really question the cause of inequalities, and for that it is necessary to question our relationship with the land – relationships which also map onto other relations of power. We must understand then, that there are other ways to relate to the Earth. Other meanings, cosmovisions and alternative ways of understanding the world already exist, and they are found in our peoples and our [indigenous] languages. For that reason it’s important to tell these stories, and also why I am part of Futuros Indígenas.

What am I defending and why now?

Telling the story from the side of the people has never been easy, but as women we have organised to work together, to confront these violences that cut through both us and the land, by deciding to heal ourselves with the Earth.

In COP26 we participated with a group of women called Defenders of the Earth, of which Futuros Indígenas is a part. There was never any hope for COP, but as part of a group, we returned strengthened by having known and met so many other women, people, and youth that are seeking profound changes in a bid to save life itself. Like us, they denounced the consequences of what is called ‘development’ in their territories and planted the seeds of other alternatives.

One of the most important spaces in Glasgow was the Earth’s Cure global assembly of indigenous women. In this space, we came together to share what motivated us to continue fighting against this violence and pain we suffer against. One of the most important lessons from the assembly was that women need to join this fight to put life at the centre.

We also need to cure ourselves, not just the Earth. Our pains have been the same as those of our grandmothers, and those of our ancestors which means there is value in finally naming these violences. The defence of the land is the defence of our own body because we cannot understand ourselves as separate, and it is us women defenders of our territories who are naming and visibilising these injustices.

What’s up with the language?

In climate change decision-making spaces (like COP), other languages, other epistemologies, other cosmovisions are not recognised. They engage from just one understanding of nature, and just one understanding of gender relations. For us as indigenous women, it’s important to question the principles that give meaning to this language, and acknowledge that there are many alternatives already that actually permit us to think about the world in a different way.

The link between the land and body arises because we cannot think about the land without considering its interaction with the people that live on the land. That’s why understanding the climate crisis cannot be detached from the systems of domination that confine us. However, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) only discovered that this year, naming in their most recent 2022 report that the climate crisis is a consequence of colonialism. Language matters, the stories that we tell matters, if we really want to build worlds that are truly inclusive and equal.

"Language matters, the stories that we tell matters, if we really want to build worlds that are truly inclusive and equal."

Want to learn?

When we speak about climate and gender justice, we should prioritise the life histories of women who fight for the land from many different spaces, and against the extractivist and patriarchal violence. That’s why for CSW66 we are inviting you to change the narratives about the climate crisis to put life and land in the centre.

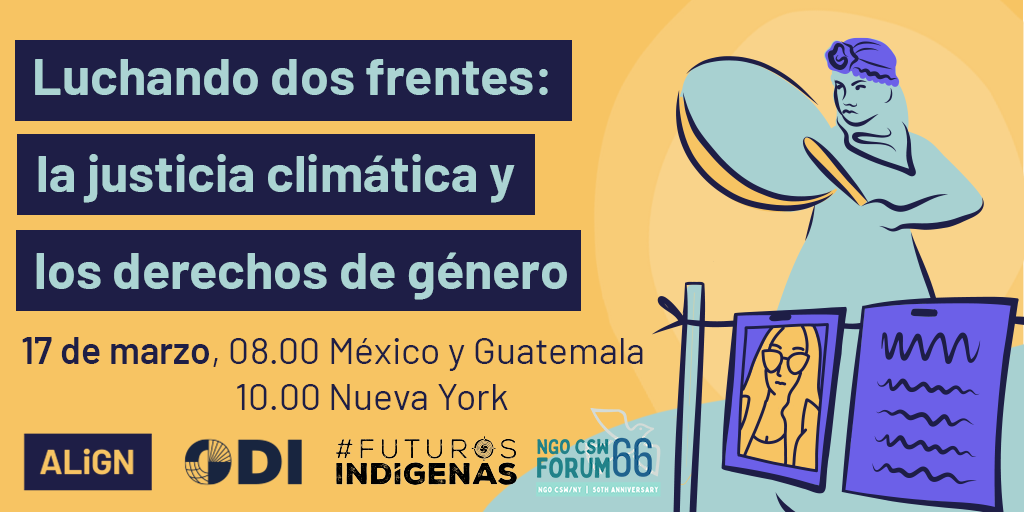

Join us today for an exclusive bilingual CSW66 event this Thursday 17 March at 8am Mexico | 10am EST | 2pm UK. Click the image below to find out how to join.

Co-hosted by Carmen Leon-Himmelstine and Mitzy Violeta from ODI and Futuros Indigenas, we’ll be hearing directly from just some of these women, speaking about their realities from their ancestral lands in Abya Yala:

Guests include:

● Erandi Medina, who fights against the avocado monocultures in Michoacán, Mexico, with a group of women seeking to ensure the community does not lose its link with the forest or its history;

● María Choc, who has fought against the palm-oil monoculture industry in Guatemala, been an interpreter and translator of her maternal indigenous language q’eqchi to Spanish, and has helped women facing situations of violence.

● María José Andrade, who is an Amazonian climate activist and indigenous rights defender from Kichwa de Serena in Ecuador.

Español por Mitzy Violeta

“En tiempos de crisis climática, el futuro es un territorio a defender.”

Para las mujeres defensoras del territorio es muy claro las causas de la crisis climática y la emergencia ecológica.

Es en la lógica del extractivismo - donde se articula el capitalismo, el colonialismo y el patriarcado. Éstos no sólo dañan a la tierra, sino que implantan violencia y división entre nuestras comunidades. Afectan nuestra salud, nuestras formas de vida, y nuestra relación con la naturaleza. Quienes vivimos las consecuencias en nuestros territorios no podemos sólo hablar del ‘cambio climático’. Necesitamos nombrar la urgencia, porque están destruyendo nuestros territorios y la forma de nombrar el problema puede ayudar a visibilizarlo.

Una de las tareas que tenemos ahora es seguir sembrando esperanza, por medio de contar las historias de nuestros pueblos y nuestras propias historias de vida para mostrar las verdaderas consecuencias de la crisis climática, que es una crisis de la vida en general - que debe entenderse desde las experiencias en los territorios. Esto es porque la crisis climática es un síntoma de un sistema desigual, capitalista y patriarcal que reproduce desigualdades extremas e injusticias. Nosotras las mujeres vivimos las consecuencias de la crisis pero también vemos las causas, es la lógica del extractivismo.

¿Por qué soy activista?

Cuando parecía que todo estaba perdido, decidimos organizarnos. Soy Mitzy Violeta, mixteca de San Sebastián Tecomaxtlahuaca, Oaxaca. Desde pequeña me causaban inconformidad las injusticias, aunque no sabía muy bien su origen, pero esa inquietud fue la que me llevó a tejerme en los movimientos con otras compañeras.

Primero, organizamos movimientos desde la ciudad para enfrentar el racismo y tener un espacio seguro con otras compañeras rurales y migrantes. Después, a través de ese proceso, pude reconocer la importancia de nombrarme desde mi comunidad y en relación con mis raíces indígenas ancestrales. También supe que tenía que tomar acción para cambiar esas situaciones por las que yo misma había pasado, por eso me uní a distintas agrupaciones vinculadas con pueblos y mujeres indígenas.

Más recientemente encontré que esas injusticias que nos atraviesan como mujeres indígenas también atraviesan al territorio. Y, la motivación más grande para organizar estos movimientos y articular estas luchas ha sido pensar, ¿Qué alternativas son posibles y qué sociedad queremos construir?

"encontré que esas injusticias que nos atraviesan como mujeres indígenas también atraviesan al territorio."

Alternativas que realmente cuestionan las desigualdades y para eso es necesario cuestionar nuestra relación con los territorios - que también se convierten en relaciones de poder. Así, debemos entender que hay otras formas de relacionarse con la tierra. Otros significados, cosmovisiones alternas y otras maneras de entender el mundo ya existen y están en nuestros pueblos y en nuestras lenguas. Por esta razón es necesario contar estas otras historias, por eso soy parte de Futuros Indígenas.

¿Qué defiendo y por qué ahora?

Contar las historias desde los pueblos nunca ha sido fácil, pero las mujeres nos hemos organizado para trabajar juntas, ante esas violencias que nos atraviesan y atraviesan el territorio, hemos decidido sanarnos con la tierra.

En la COP26 participamos como parte de un grupo de mujeres llamado Defensoras de la Tierra. que también es parte de futuros indígenas. Nunca hubo esperanza en la COP, pero nosotras como parte de un grupo regresamos fortalecidas porque encontramos a muchas mujeres, pueblos y juventudes que están buscando cambios profundos para salvar la vida. Como nosotras, ellos denunciaron las consecuencias del supuesto “desarrollo” en sus territorios y plantaron las semillas de otras alternativas.

Uno de los espacios más importantes en Glasgow fue la asamblea global de mujeres indígenas Cura Da Terra. En este espacio nos unimos para compartir aquello que nos motiva a continuar luchando y las violencias y dolores que enfrentamos. Uno de los aprendizajes más importantes de la asamblea fue que las mujeres debemos unirnos en esta lucha por poner la vida en el centro.

Necesitamos curarnos también a nosotras, no solo a la tierra. Nuestros dolores también han sido los de nuestras abuelas y ancestras y eso implica tener el valor de nombrar las violencias. La defensa del territorio es la defensa de nuestro cuerpo porque no puede entenderse de manera separada, y las mujeres defensoras del territorio somos quienes estamos nombrando y visibilizando estas injusticias.

¿Qué pasa con el lenguaje?

En los espacios de toma de decisión sobre el cambio climático (como COP), no se reconocen otros lenguajes, otras epistemologías, otras cosmovisiones. Se trabaja desde una sola idea de naturaleza, una sola idea de las relaciones de género. Para nosotras mujeres indígenas, es importante cuestionar los principios que dan significado a esas palabras y reconocer que hay muchas más y eso permite pensar el mundo de manera diferente.

El vínculo territorio cuerpo es planteado porque no podemos pensar el territorio sin su interacción con las personas que lo habitan. Por eso el entendimiento de la crisis climática no podría separarse de los sistemas de dominación que nos rigen. Sin embargo, el IPCC sólo lo descubrió hasta este año, al nombrar en su informe de 2022 más reciente que la crisis climática es consecuencia del colonialismo. El lenguaje importa, las historias que se cuentan importan, si queremos construir mundos verdaderamente incluyentes y equitativos.

"El lenguaje importa, las historias que se cuentan importan, si queremos construir mundos verdaderamente incluyentes y equitativos."

¿Cómo aprender?

Por eso cuando hablamos de justicia climática y justicia de género debemos priorizar las historias de vida de mujeres que luchan desde distintos espacios por el territorio, y contra la violencia extractivista y patriarcal. En el marco de CSW66, les invitamos a cambiar las narrativas sobre la crisis climática para poner la vida y la tierra en el centro.

Ven a nuestro exclusivo evento bilingüe este jueves 17 marzo a las 8am México | 9am Ecuador | 11am Chile | 3pm España. Haz clic en la imagen debajo para saber como unirse.

Coorganizado por ODI y Futuros Indígenas, vamos a escuchar directamente de solo algunas de esas mujeres, conversando sobre sus realidades desde sus territorios ancestrales de Abya Yala.

Invitamos a:

● Erandi Medina, que lucha contra el monocultivo de aguacate, en Michoacán México, con un grupo de mujeres sanadoras que buscan que la comunidad no pierda su vínculo con el bosque o la historia.

● María Choc, que ha luchado contra el monocultivo de palma aceitera en Guatemala siendo intérprete y traductora del idioma materno q'eqchi al español intérprete y ha ayudado a muchas mujeres que enfrentan situaciones de violencia.

● María José Andrade, quien es una activista Amazónica que lucha por el clima y por defender los derechos indígenas de Kichwa de Serena en Ecuador.