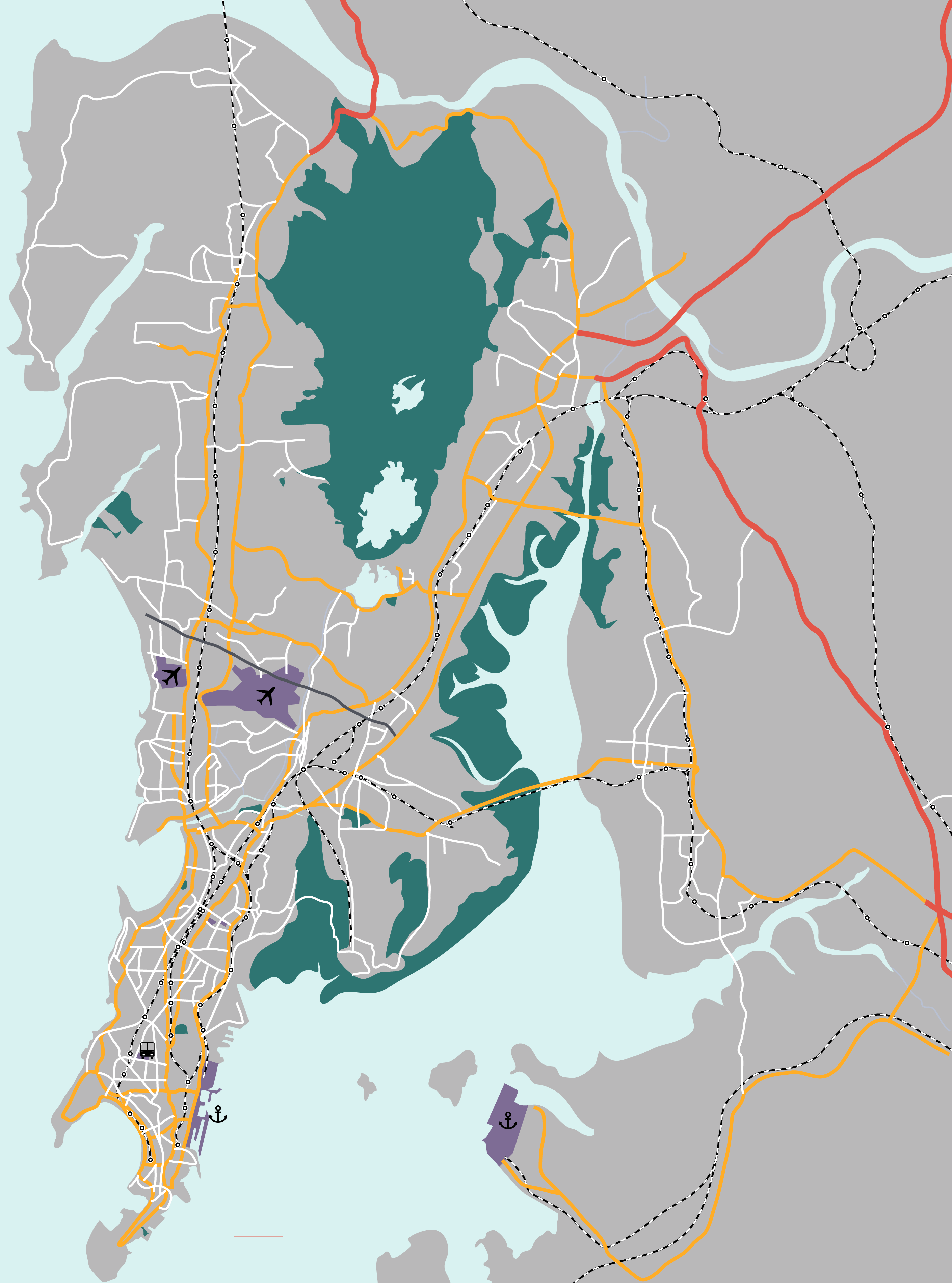

Greater Mumbai has one of the highest population densities in the world, with more than 18 million people crammed into this bustling and strained city.

This city is almost split in two: to the south, the city centre perched on reclaimed land, to the north-east vast sprawling suburbs. The housing is unaffordable in the Island City centre, so most people live in suburban Mumbai or beyond. The population of the suburbs overtook Island City in the 1970s and has been growing rapidly ever since.

More than 5,700 people died on the roads of Mumbai between 2006 and 2016.

The city’s tremendous growth and its geography puts great strain on its infrastructure. To get to work, people rely on the rail and bus networks. The rail network sees 7 million trips a day. Despite congestion making them slow, buses facilitate 5.5 million journeys a day – half a million more journeys than are made on the London Underground. Travel costs are high, too.

Attempts to address road safety must grapple with the the prevailing view that being safe on the roads is a personal responsibility independent of the local regulatory, transportation and infrastructural conditions.

The average person living in Mumbai spends 11% of their total income on public transport. The poorest pay 16%. This expensive, high-volume mass transit system is unable to meet demand. A problem exacerbated by the fact that services are badly linked, forcing travellers crossing the city to route through the centre.

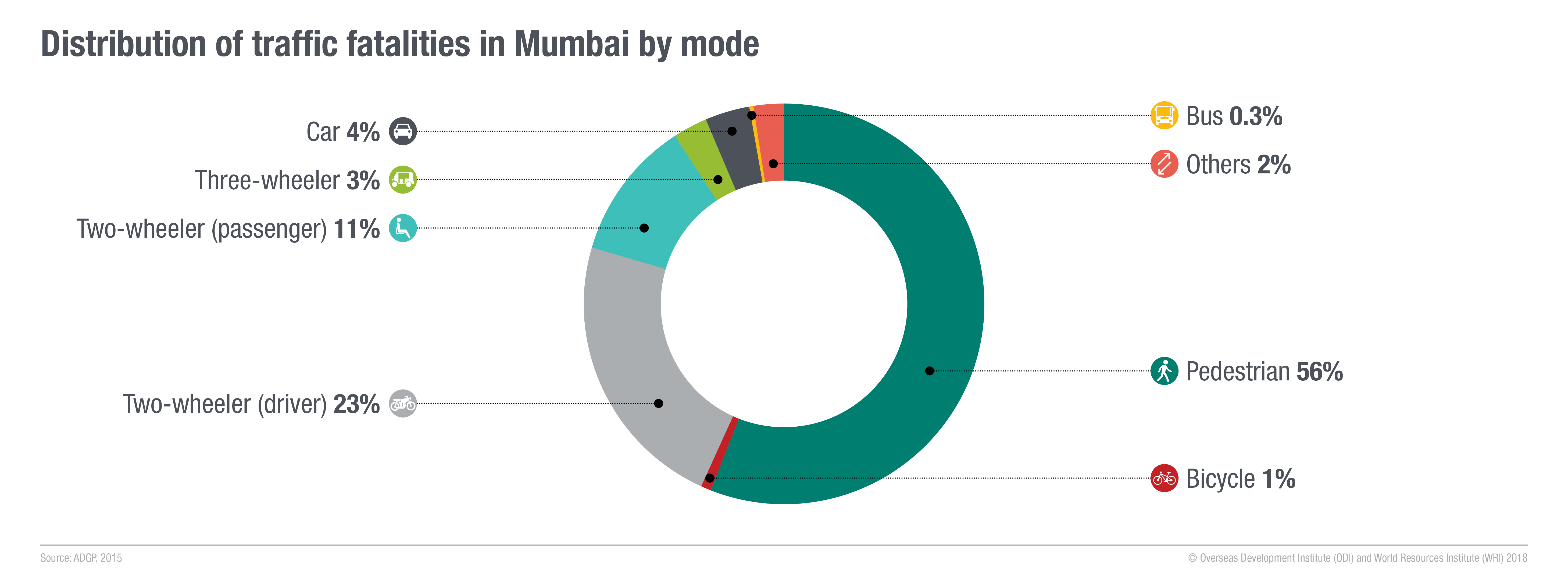

Traffic collisions claim the lives of two people every day. Vulnerable road users – typically travelling by exposed modes of transport like walking and cycling – account for more than 90% of fatalities and over half of these fatalities are pedestrians. This is part of a broader, worsening problem in India. Last year, road crashes cost the government about $8 billion, or 3% of the national gross domestic product. And this is as well as the financial, economic and emotional effect on the families affected.

In 2015, India's Supreme Court issued directives requiring all states to prepare road safety action plans.

In recent years, the Indian government has paid increasing attention to road safety due to international and domestic factors. Yet decrees from above have not translated into action on the ground. The Motor Vehicles Act – established almost 30 years ago – required that states create Road Safety Councils. Another 21 years passed before a Council was set up in Maharashtra – involving representatives from across the state government. But the Council has no authority to make any decisions, no backing in law, and no money. And their focus is on cars, not pedestrians or cyclists.

In 2010, the National Road Safety Policy was published. All levels of government are meant to prioritise safer infrastructure, safer vehicles and safer drivers, with states advised to create their own version of the national-level policy. But, in most cases, policies are duplicated, word for word, showing just how little thought is put into road safety at this lower level.

More positively, in the same year, public interest litigation demanding action on road safety was filed in Mumbai, and the resulting recommendations do seem to be having an impact: in 2016, for the first time in four years, the number of fatalities has dropped.

In Mumbai, road safety is viewed as a problem with behaviour not a problem with design. Consequently, the government prioritises building new roads instead – an approach that is popular because it benefits car-users, who also tend to be powerful and wealthy. Road safety and other transport infrastructure changes are not popular: their impact is less visible and there is little demand for change among influential groups.

The current transport minister has made road safety a government priority, but has been unable to pass relevant legislation. He has been blocked by the opposition, other members of the legislature, and independent bodies (like the transport unions car lobby) protecting their own interests – all of which suggests the establishment are unwilling to see poor infrastructure as a contributing factor to poor road safety.

Road safety is commonly viewed as the personal responsibility of individuals. This perception is used to excuse systemic road safety failures.

This unwillingness is exacerbated by a commonly-held view that road safety is the personal responsibility of individuals. Risky behaviour – which is often the result of inadequate infrastructure – reinforces this perception, and is used to excuse systemic road safety failures.

The limited demand – among both the public and policy-makers – to prioritise road safety means that while progress is being made, it is slow and faltering, and recent gains are at risk of being reversed by the construction of more poorly designed, high-speed roads.

National calls for road safety reform have had little impact at the local level. Politicians focus on new major road projects, without integrating road safety considerations – an approach that is seen as more tangible and politically feasible. A Supreme Court ruling that requires states to create road safety plans may improve things but the need to advance other reform avenues remains.