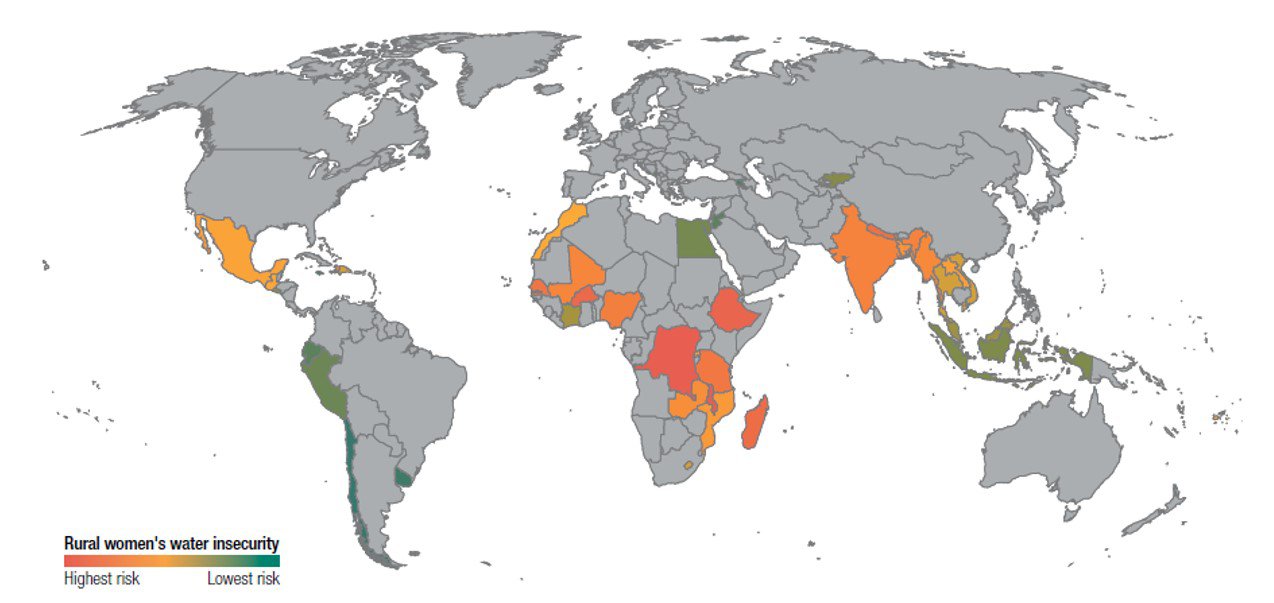

Climate hazards can be devastating, as the El Niño-related droughts in the Horn and Southern Africa show. Many developing countries continue to rely on rain-fed agriculture for both economic growth and livelihoods. When rains fail, rural communities face food insecurity and limited livelihood options. However, the impacts of climate risks are not felt equally and groups such as women and poorer people are particularly exposed.

Women and men have different access to, control over, rights and responsibilities in relation to land and water for agricultural production and domestic tasks. As our new research shows, these affect women’s capacity to build resilience and use coping strategies at times of crisis.

Here are three key steps to reduce rural women’s vulnerability and build resilience:

1. Plan ahead for seasonal water scarcity and account for multiple uses of the same water source

In sub-Saharan Africa women are primarily responsible for securing water for drinking, washing, cooking and cleaning. When water supplies are threatened during the dry season or drought periods, women must walk further, wait for longer and rely on lower quality water to provide for their household. This creates mental and physical stress.

In Mitawa village, Malawi, women described how the nearby borehole was more likely to fail in the dry season, forcing them to fetch low quality water that gave their children diarrhoea and affected school attendance.

When the borehole breaks we use the river for our household needs but the quality is poor and there is a risk of diarrhoea. It is also far to walk.Women's focus group in Machinga, Malawi.

The dry season is also a critical time for farming, when crops are thirsty for irrigation water. There were reports that irrigation use was prioritised over other activities such as washing, suggesting women had little influence in decision-making.

And when women spend their time and energy collecting water, it restricts the time they have to engage in other productive activities which generate income.

To address this, donors and implementing agencies should better plan for seasonal patterns of water availability. They should consider multiple uses of the same water source, and the relationship between food and water security.

2. Improve gender-sensitive programming for rural development and agricultural livelihoods

Across the world, women own less land than men. Land and water rights are often related, and water for irrigation is frequently controlled by male-dominated water user associations.

Irrigation provides a medium term buffer against seasonal and drought-related food insecurity. However, the benefits of irrigation for women are mediated by their limited access to key assets.

For example, in Malawi, women found it more difficult to secure finances to rent land, purchase or rent equipment, and access fertiliser. This is partly explained by differences in income earning opportunities between men and women, as well as control over household finances.

Sometimes the men don’t even tell their wives what they have sold, or might spend the money on beer. If the woman wants to prevent her husband from selling maize to keep some for food, sometimes she will go straight to the mill for pounding.Women's focus group in Ntchisi, Malawi.

Implementing agencies are aware of these dynamics, but empowering women takes time, and disrupting existing social hierarchies is difficult.

Programmes must continue to adopt gender aware approaches, and build alliances with men with the medium to longer term goal of female empowerment which also supports the entire community.

3. Continue to strengthen women’s livelihoods in rural areas, while maximising the benefits of migration.

Migration is an important strategy to cope with seasonal food and income shortages, or the impacts of droughts or floods on production. In many parts of Africa, social norms and limited assets and skills means women have fewer options to pursue off-farm work in nearby cities or industries.

In Malawi, men mostly migrate to cities and neighbouring countries such as South Africa, and send back remittances to their wives and families. However, the impacts on women left behind are mixed. Some complained their husbands’ contributions were unreliable or inadequate, and that they felt abandoned. Single mothers and widows struggle to maintain their farms without extra labour or a supplementary income.

However, this also gives women an opportunity to make critical decisions about farm management, and may lead to a shift in gender norms. In times of climate crisis, however, their limited mobility puts women at greater risk.

Governments and their development partners should strengthen opportunities for rural women to earn income which is not completely dependent on the farm, for example through micro-enterprises. Meanwhile, policies should maximise the benefits of migration from the farm to other areas through supporting financial flows, for example through mobile banking which targets women as senders or receivers.