Last year, with the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the world made a promise that by 2030 all girls and boys would complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education. Emergencies and protracted crises are one of the biggest challenges to reaching that goal.

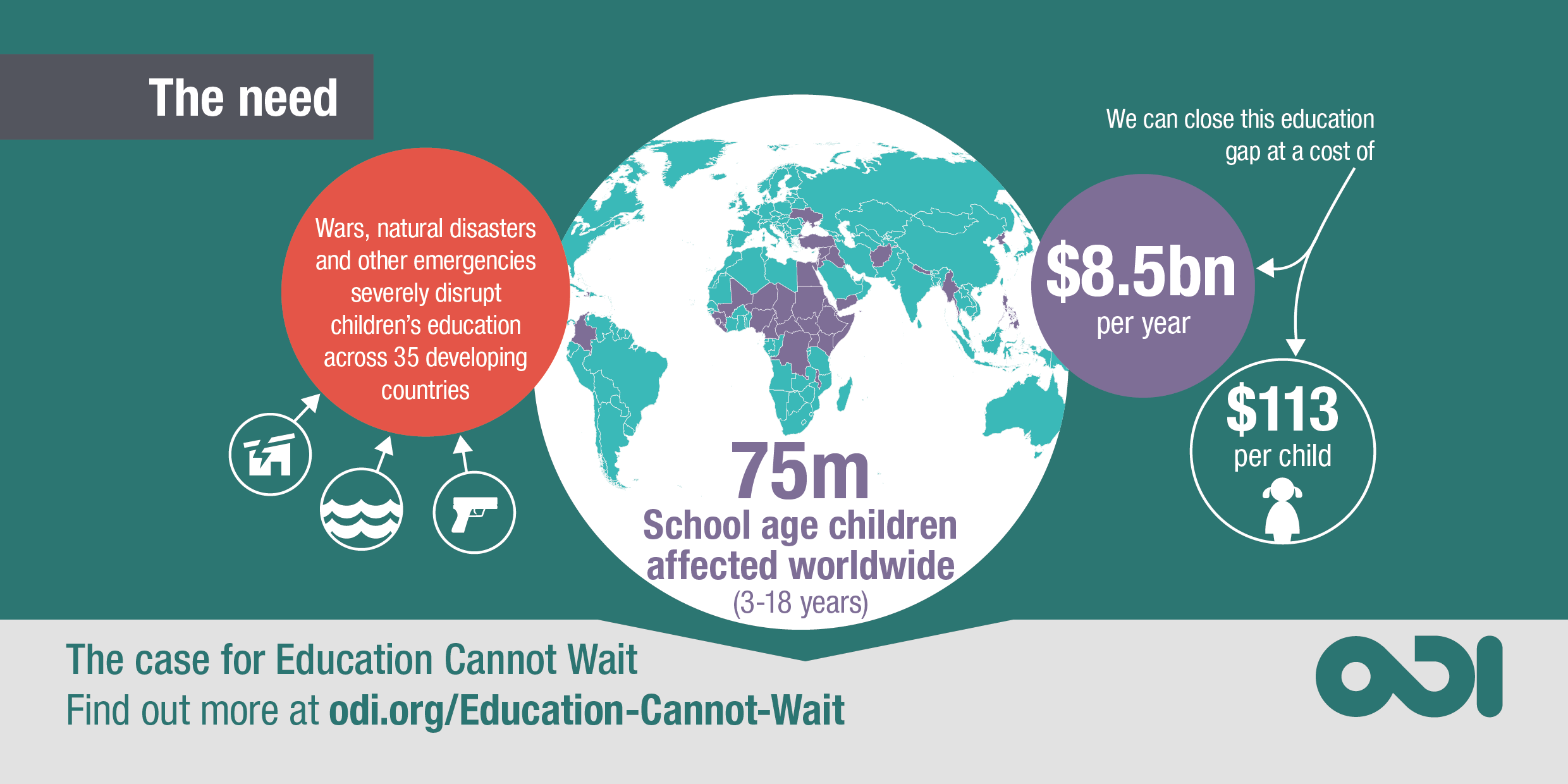

In 2015 alone, nearly 75 million school-aged children and youth (3-18 years old) across 35 crisis-affected countries had their education disrupted. Governments need an extra $8.5 billion a year to close this gap. This may sound like a staggering amount, but works out to only $113 per child per year.

As we head towards the World Humanitarian Summit later this month, ODI has worked with a number of others to set out how the global community could come together to address this need and improve education in crisis-hit areas.

What’s not working?

There are five major problems with business-as-usual approaches:

1. Low priority. Governments too often fail to reach out to vulnerable groups like refugees with education. International humanitarian actors typically provide uneven support to education in emergencies, and development actors frequently stop operating in crisis contexts.

2. Poor coordination. Breakdowns between governments, humanitarian and development actors – who all have different mandates – in assessments, planning and financing can lead to disjointed approaches and priorities.

3. Insufficient funding. Despite an increased number of crises, and mounting need, funding for education in emergencies has almost halved since 2010, with less than 2% of all humanitarian aid going to education in 2015. Development funding to education in crisis contexts only reached 9% of total ODA for education in 2012, and has likely dropped since.

4. Inadequate capacity. In many places, there are few teachers, senior staff and administrators skilled in crisis response or supported by adequate and resilient systems. And due to uncertainty in funding, international actors often only provide short-term and stop-gap deployments.

5. Lack of data and analysis. Ineffective and, at times, parallel information systems regularly leave gaps in data for education and crisis, with poor real-time data collection.

These issues aren’t new – so why address this now?

The political momentum is right.

Following the failure to reach education goals under the Millennium Development Goals and Education for All initiatives, the SDG era is an opportunity to do better. Several major political actors are pushing for change and are ready to back bold new efforts.

In the lead-up to the World Humanitarian Summit, there is also significant interest in radically new approaches that join up humanitarian and development efforts.

Crucially, there is growing interest from new and established donors alike to explore joint and innovative mechanisms to finance education in crisis, including in the work of the International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. A bold proposal on how to raise and channel new finance to the sector will be welcomed.

And evidence increasingly shows that education improves life chances and is highly prioritised by crisis-affected communities.

A proposal for a new platform for education in emergencies

Built on extensive consultation and dialogue with affected governments, donors, non-governmental organisations and academics, our proposal details how a new education crisis platform would work.

Comprised of an Acceleration Facility, focused on investing in existing actors to improve education response, and a Breakthrough Fund, which will support both rapid and multi-year country level engagement, the platform has five main functions:

- Inspire political commitment

- Joint planning and response

- Generate and disburse new funding

- Strengthen capacity

- Improve accountability

In the face of chronic patterns of disruption and exclusion, ensuring education for children and young people affected by crisis truly requires a shift in global approaches and ambition.

The proposal for this new fund shows how transformation could happen, with governments, humanitarian and development actors joining up to deliver more collaborative, agile and rapid response to fulfil the right to education and keep the SDG promise.

Want to find out more? Read our FAQs:

Frequently asked questions

How will the fund work in crisis affected countries?

Joseph Wales, Research Officer:

South Sudan was one of two countries we visited while preparing the Education Cannot Wait proposal. The country has suffered from decades of war, resulting in some of the worst human development indicators in the world.

It now faces a complex humanitarian emergency, with large swathes of the country controlled by opposition groups and in active conflict since 2013.

In South Sudan, Education Cannot Wait would use both of its two windows: the Breakthrough Fund and Acceleration Facility.

The Breakthrough Fund would provide long-term funding to draw together government, humanitarian and development actors (utilising the Education Donor Group), to develop a costed, multi-year strategy linked to existing education and humanitarian response plans.

It would use a flexible disbursement mechanism and procurement facility to bridge across phases of the response, while the role of national organisations would be boosted by allowing them to access funds directly and by mandating international partners to implement multi-year plans with and through local agencies. These approaches would also contribute to raising national capacity.

Alongside this, the Acceleration Facility would support organisations to raise the profile of South Sudan’s education needs internationally and bringing national actors together to seek solutions for the education crisis, particularly outside of government held areas.

It would also enable provision of increased technical support, such as expertise on planning processes and needs analysis; development of a human resource strategy for education; harmonising indicators; and documenting successful cases of transition and co-operation between agencies across emergency phases.

If the fund is able to provide sufficient support, the impact could be enormous.

South Sudan could safely return to school 967,000 children whose education has been disrupted.The country could restart construction of its education system – before the crisis less than half of children were enrolled in primary and fewer than one in twenty in secondary.

Frequently asked questions

Where do we find the money?

Romilly Greenhill, Team Leader, Development Finance

The education crisis platform will need money – big money. The platform’s ambition will be to raise $150 million in the first year, scaling up to $1.5 billion by year five – a total fundraising target of $3.85 billion. It is vital that this funding is new – not simply reallocated away from existing spending.

The platform will take advantage of the new development finance landscape to bring in new donors, including official donors, the business and commercial sectors, foundations, philanthropic donors, high-net-worth individuals, the international NGO and faith communities, and innovative financing. It will do this by:

- Building the investment case, to better document what works and what it costs

- Improving collective action, by streamlining the coordination architecture

- Developing clear, country-specific funding strategies, backed by evidence

- Building effective relationships with core donors, mapping the potential donor landscape, and solving financing bottlenecks globally and at country levels

- Creating new pipelines and pathways, particularly for new donors and private sector actors to engage.

The platform will also work with new and existing donors and governments to support them to scale up funding to this sector, including through:

- Support for non-Development Assistance Committee donors to include emergencies within their education portfolios

- A menu of pre-vetted charities for the private sector to donate funds

- Innovative and catalytic investment opportunities for foundations

- Expenditure benchmarks for government commitment to education

- Matching impact funding mechanisms with government, private sector and public contributions.

Frequently asked questions

How did we arrive at these numbers?

Arran Magee, Research Officer

Our calculation of the number of children whose education has been affected by crises was drawn from UNICEF’s 2015 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal and 2015 United Nations Population Division (UNPD) population data. We found that 75 million school-aged children between 3 and 18 years, of a total of 462 million children living in 35 crisis affected countries, are in urgent need of support. Until now, the number of children whose education has been affected by emergencies has typically been illustrated through calculations of children out of school in conflict affected countries. The 75 million differs in that it includes all children significantly affected – not just those out of school longer-term – and covers conflict, natural disasters and other types of crises.

Next came the cost estimate for this group, which we averaged at $11.6 billion annually. Four major drivers of cost for education in emergencies were identified: classroom infrastructure, teacher payments (either salaries or stipends), teacher training and education supplies, with high and low estimates across three geographical contexts – Asia, Africa and Latin America. Using this data, a classroom cost was calculated for each age group and a crisis premium was added, drawing on UNESCO’s ‘ mark-up of per student costs to attract marginalized children’.

Our approach differs from others in that it focuses on the cost of restoring education during or after a crisis, not provision of a full year of schooling (which is of course needed in some – but not all – cases).It was then important to further incorporate the estimate of pre-existing domestic funding. The EFA GEM examines how total education costs will need to increase in low and lower- middle income countries over 2015-2030 if they are to meet the Sustainable Development Goals. Using this data we were able to estimate current domestic funding, then factored in challenges in revenue raising and public spending based on research of fragile states, to establish a funding gap of or $8.5 billion for all 75 million children, which works out to $113 per student.

As these are global figures, there are of course limitations to these estimates, with more detailed analysis required at a country level as the fund begins to operate. The lesson however remains the same: millions of children are affected by crises and their education is significantly underfunded.

More information on counting and costs can be found in Annex 1 of A common platform for education in emergencies and protracted crises: evidence paper .