The UN called the food crisis in East Africa the world’s ‘worst humanitarian crisis since 1945,’ generating headlines around the world and propelling the East Africa appeal to £40 million in just two weeks. After all this success, does it even matter that it’s not true – and beside the point?

The emphasis on emergency fundraising deflects attention from the structural causes of poverty and famine, evoking pity and charity. But what we need is outrage and the desire for preventative action and political solutions if we are to prevent such crises from happening again.

Let’s start with the facts

Based on numbers alone, this is not the worst humanitarian crisis since 1945. 20 million people are at risk of famine and starvation in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, north-eastern Nigeria and Yemen, yet an estimated 45 million died from 1958 to 1962 in China’s great famine.

Quantifying the scale of a crisis is important – numbers provide a crucial foundation for any humanitarian response. But numbers can also be misleading, as are words like ‘worst’ and ‘unprecedented’. Such language creates the sense that the situation in East Africa is inevitable and unmanageable, drowning out analysis in the media of the different and complex causes of famine in each country. It also creates a sliding scale of human suffering – only the most heart-wrenching or urgent emergency deserves our attention.

The reality is: this crisis is mostly man-made and preventable.

Food insecurity is a recurrent problem in East Africa. In 2011, more than a quarter of a million people died in Somalia, half of them children under five. The East Africa famine isn’t just a lack of food caused by drought, it’s also caused by poor governance, conflicts, and economic shocks that mean the poor can’t afford to buy food.

The East Africa famine isn’t just a lack of food caused by drought, it’s also caused by poor governance, conflicts, and economic shocks that mean the poor can’t afford to buy food.Each East African country facing famine today has experienced some form of political and economic crises coupled with protracted and violent conflicts, creating a lethal cocktail for the people living there.

Crisis fatigue

When we think back to Ethiopia and Live Aid in the 1980s, people were shocked by horrific images of starving children beamed via television into their living rooms. Now, scenes of suffering children in destroyed cities such as Aleppo or rural Somalia are a daily occurrence on TV and social media. Shock tactics and tugging at heartstrings can boost cash contributions for a limited time, but such hyperbole ultimately desensitises us to high levels of suffering.

The Syrian refugee crisis – another ‘worst crisis since World War II’ – is emblematic of such fatigue. When the UN launched its fundraising campaign for Syria in 2013, 68% of the appeal was funded. Declining interest saw this amount fall to just 51% in 2014, and to 43% in 2015.

Aid industry stuck in crisis mode

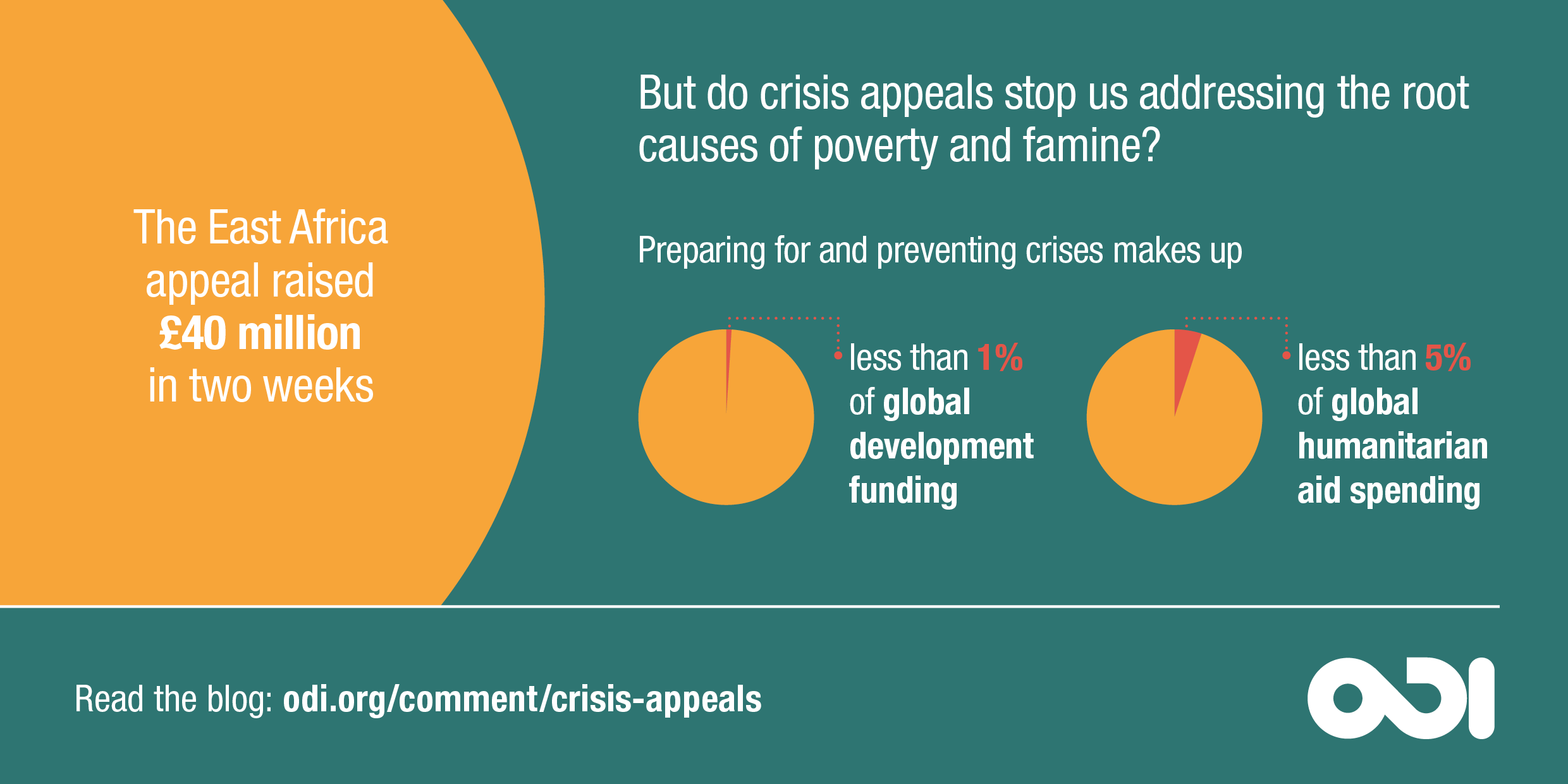

Part of the problem lies with an aid system designed primarily to respond to crises, rather than prevent them. Currently, less than 5% of humanitarian aid and 1% of development funding is spent on preparedness and prevention.

Part of the problem lies with an aid system designed primarily to respond to crises, rather than prevent them.Equally culpable are the development investments and political processes that have failed to resolve the protracted conflicts that push countries and communities to the brink.

So, rather than using fear and pity to raise awareness and funds, why not use social and mainstream media to tap into public outrage and activism and address what put these countries in crisis in the first place?

This means putting pressure on politicians to invest political capital and energy into ending conflicts. It also means pushing aid agencies and their donors to act early and with a substantial injection of funds to prevent loss of life and human suffering where we know it is likely to occur.

Finally, it means redefining success in the aid system so that a crisis avoided is valued more than a crisis resolved. Avoiding humanitarian crises could save money and more lives than continuing to focus on emergency response. Headlines like ‘Famine averted in East Africa’ might elicit less pity, but they would mean far more for countries and communities locked in cycles of hunger and poverty.