The High-Level Political Forum, at which ministers arrive today (although sadly some countries are sending lower-level representation) is the only official space for monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). That’s a heavy lift, and to be successful it needs to be a place where all challenges and threats to progress – as well as merited (and otherwise) peacocking and learning from the progress of others – are outed.

Last year’s theme was 'leave no one behind' – a SDG commitment which not only cuts to the heart of what progress needs to look like, but will take down the entire SDG agenda if not achieved. While not every accountability moment should have a unique focus on the SDG’s explicit promise to prioritise the needs of the furthest behind, reporting against this metric must be included every year.

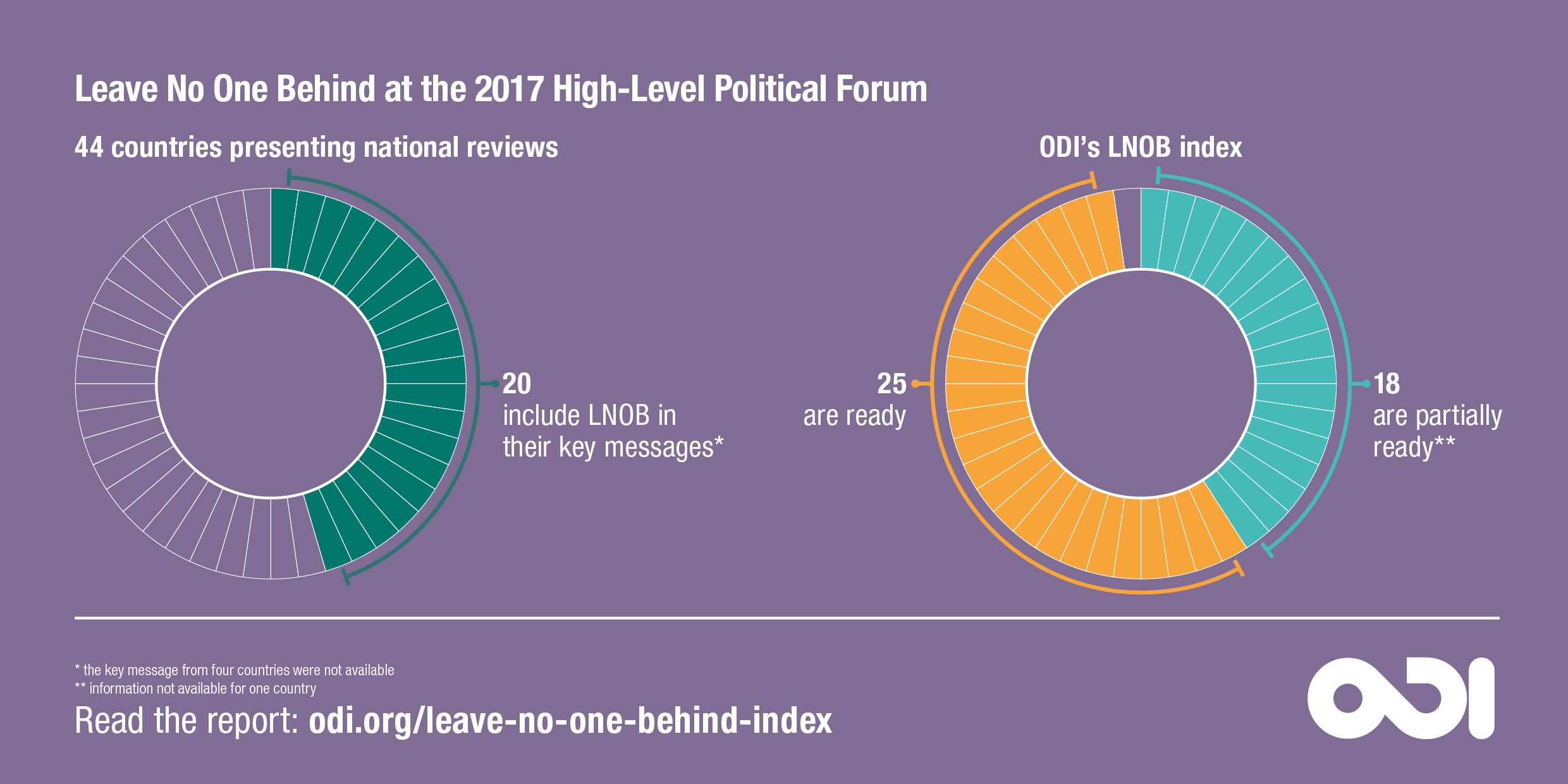

Significantly, of the 44 countries who have volunteered to present their picture of progress next week around half have taken up this challenge, and have included 'leave no one behind' in their key messages to the HLPF.

In some cases, such as the Maldives, it’s a laudable recognition that improvements need to be made. Significantly, Nigeria says that an ‘entire section’ of its recent National Economic Recovery, Growth Plan is focused on policy commitments around social inclusion to ensure 'no one is left behind'. Tajikistan proposes to ‘pay particular attention’ to data disaggregation, a bedrock for systematic improvements for the poorest and marginalised.

In others, it’s a factual statement of progress: Indonesia flags that it already has 87 indicators (and 234 proxy ones) for which it has disaggregated data. Ethiopia says that it has undertaken affirmative action ‘particularly to support women and girls and to build capacities of those who are/or which have been left behind because of historical reasons’.

The Netherlands’ statement clearly underlines that leaving no one behind requires action at home as well as changes to their development co-operation. It says: ‘As we make a leap forward we have to ensure that no one is left behind. This challenge is relevant to both richer countries like the Netherlands, and to developing countries, where the challenge is even greater’.

A useful counterpoint to these political commitments is the ODI 'leave no one behind' index – an assessment of the extent to which these 44 governments (actually 43 as there was no data available for Monaco) are already set up to meet this commitment, which we’ll launch at the HLPF.

The index measures the countries’ readiness in three areas:

- Data: have household surveys been conducted recently?

- Policy: do countries have some of the core policies in place: are health services free at the point of access; are there anti-discrimination policies in employment; and can women own land?

- Finance: do governments meet agreed spending targets in health, education and social protection?

It shows that 25 countries are well-placed to implement the 'leave no one behind' agenda. This is particularly the case in Latin America. Panama fulfils all three indicators, while Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Peru and Uruguay do so on two.

But 18 low- and middle-income countries are not yet in a place to 'leave no one behind' if it is to be realised by 2030, and will need to quickly work with donors to get the right systems and policies in place. ODI research has shown that, a little like paying into a pension, the later countries leave it to start implementing 'leave no one behind', the more 'expensive' (in terms of effort required) it will get – so they have every incentive to do this now.

Ethiopia is a striking exception. It is rated highly on two of the areas, but on policies it was a more mixed picture. It still has user fees for healthcare – although reforms have sought to systematise fee waivers, and community-based health insurance (CBHI) is being introduced – and while its Labour Proclamation contains a provision of anti-discrimination on the basis of sex, religion, political outlook ‘or any other condition’, obligations on affirmative action are not enforced. In addition, women’s land ownership is limited.

Donor countries score well but not perfectly so: on financing, Italy, Portugal, Luxembourg and Slovenia do not yet meet all three spending commitments, while Qatar has ground to make up across data, policy and financing.

Of course, not all of these – particularly the household survey – are the sole responsibility of the government. Had we looked at a wider range of policies – which we intend to do in the future – the rankings may have changed. And the financing point is also indicative only: to fully assess fiscal readiness we would have needed to have looked at distribution of spending to where the need is greatest (an exercise which we undertake in leave no one behind stocktake series. But the index is a useful pointer to areas for focus, and issues that should be discussed in New York this week.