The 19th Party Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) is expected to firmly consolidate the power of one man: Chairman Xi Jinping. Particularly if amendments to the Party constitution include Xi’s political thought; alongside Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping Theory. Our experts discuss what we can expect from this Congress and why it has global implications.

Frequently asked questions

Rebecca Nadin: Xi will focus on selling the success of the Chinese Dream

I expect Xi to reflect on the success of his ‘Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation’ (Zhong Guomeng) and the progress made in achieving the ‘Four Comprehensives’; a moderately prosperous society, reform, rule of law and Party discipline.

It’s likely Xi will focus on the progress made under his leadership towards realising the ‘Two Centenary Goals’ of 2021 and 2049. These dates are highly symbolic for Party legitimacy and targets for the achievement of clear goals.

The first goal aims to build a moderately prosperous country by 2021, the one hundredth anniversary of the CPC. Xi will surely draw attention to the Party’s success, over just the past five years, in lifting 65 million people out of poverty. If the 2021 goal is realised and the remaining 40 million are lifted out of poverty by 2020, China will have taken a significant step towards eradicating poverty in the country.

The second goal aims to make China a ‘strong, democratic, civilized, harmonious and modern socialist country by 2049’, the one hundredth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Xi’s ‘China Dream’ seeks to address domestic challenges like slowing domestic growth, industrial overcapacity and environmental pollution. It also encompasses international challenges like global terrorism, geopolitical rivalries and territorial disputes.

The 2049 initiative includes Belt and Road, China’s global socio-economic development plan, and the creation of international structures like the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation and the Asian Infrastructure & Investment Bank.

China’s 19th Party Congress should be recognised as domestic political theatre with global implications. Xi intends to deliver a ‘new world order with Chinese characteristics’ that influences approaches to many global problems. Both humanitarian and development agendas will be affected.

Frequently asked questions

Stephen Gelb: The Belt and Road must benefit, not exploit, developing countries

2017 confirmed the long-expected shift of China’s global economic policy, away from the ‘keep a low profile and bide your time’ approach defined by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, towards the ‘managed globalisation’ asserted by Xi Jinping in his Davos speech last January.

In that speech, Xi affirmed China’s assumption of global leadership by saying that China would keep its economy open, engage on global economic and climate change governance, and challenge global inequality. Reinforcing this, the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing last May saw China increase its commitment to absorbing imports from, and topping up intended infrastructure spending in, developing countries.

The Belt and Road may not be mentioned much at the CPC Congress this week but it is very much part of the strategy for the new normal in China’s domestic economy. Xi’s goal of moderate prosperity by 2021 includes reaching an average income level of close to $10,000 while eliminating extreme poverty entirely – around 40 million Chinese people remained below this threshold in 2016.

China is looking to balance these domestic goals with a significant contribution to the key Sustainable Development Goal of ending poverty in developing countries. It faces two related challenges.

Firstly, it must ensure that in developing countries Belt and Road benefits go beyond infrastructure which only facilitates resource exports that support Chinese domestic growth. Infrastructure development in developing countries must support industrial development that enables job creation for the poor.

Secondly, China must support, indeed promote, outward investment by its private manufacturing and services firms. Recent restrictions on outward investment targeted acquisitions in industrial countries by very large Chinese companies. This raises questions about the prospects for greenfield investment into developing countries by Chinese private enterprise. These firms can create many manufacturing jobs in poorer developing countries. But they make their own investment decisions rather than obeying government diktat, and the Chinese government needs to actively encourage their expansion abroad.

Frequently asked questions

Barnaby Willitts-King: Risk and opportunity in fragile situations

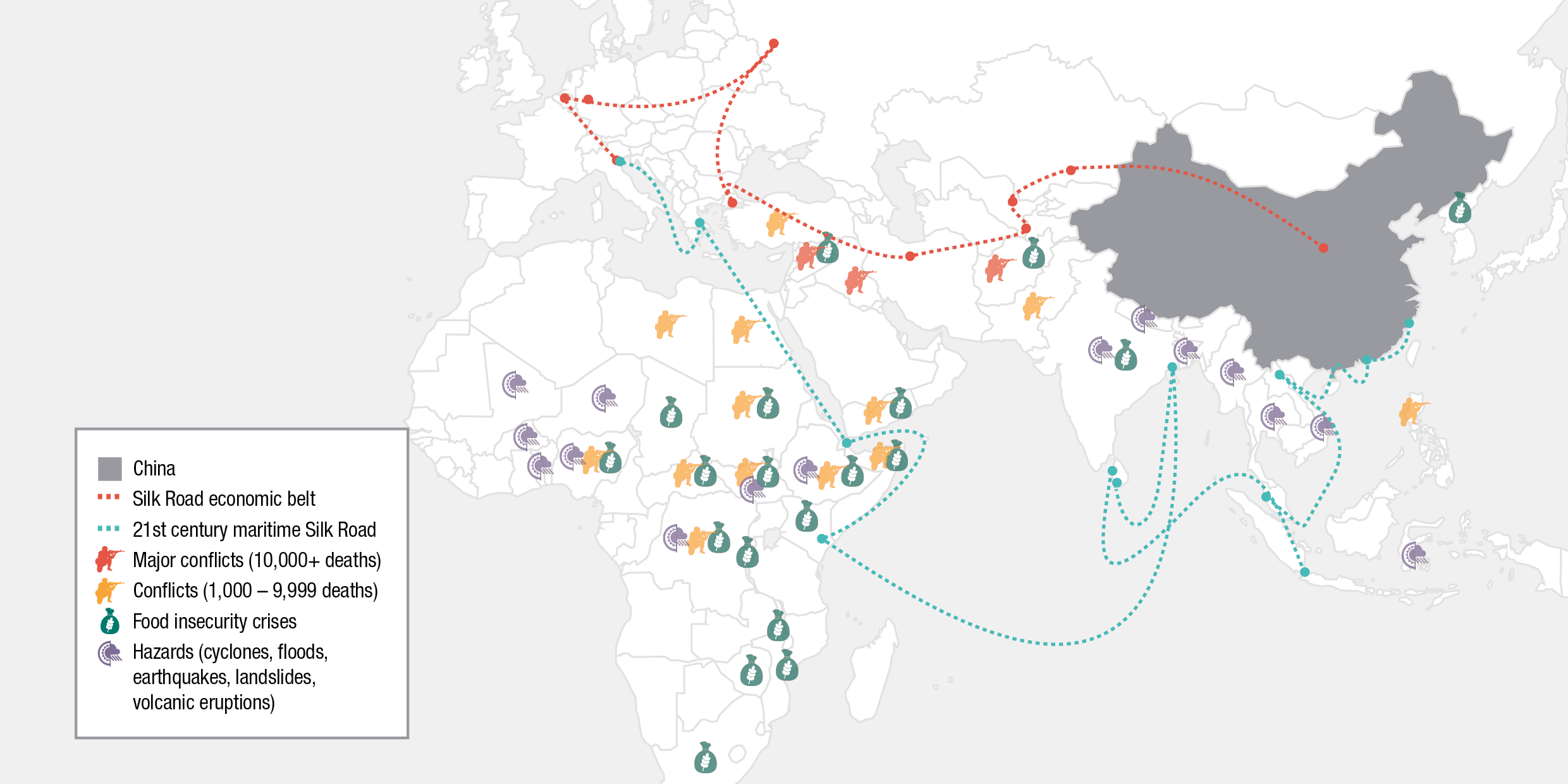

Many of the 68 Belt and Road countries are fragile or conflict-affected, including Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan. China’s investments in such countries are welcome. Particularly because, due to insecurity and a lack of regulatory safeguards, western firms and development agencies struggle to invest successfully in these challenging places. But China’s growing global footprint comes with the risk that its interests are threatened by such instability – for example when it evacuated its nationals from Libya in 2012 and South Sudan in 2016 – and it’s unlikely that the Congress will address this.

The Belt and Road could make fragile situations worse by failing to consider local conflict dynamics, particularly with respect to China’s investments in energy and infrastructure. These have already been targeted by separatist movements in Pakistan – being perceived as driven by central government and not benefitting local groups.

Using the leverage of its political and economic weight China has been quietly involved in peace processes in places like South Sudan. This growing flexibility in China’s long-held policy of non-interference may reflect a wider opportunity for positive engagement in fragile situations.

Yet, whilst it is assuming a greater humanitarian role on the world stage (to be explored in a forthcoming Humanitarian Policy Group report), its ‘capacity to assess country and political risk is not keeping pace with its sprinting ambitions’.

This suggests a need for greater coordination across China’s different policy objectives – economic, security and humanitarian. China and its international partners must be more willing to work constructively together in fragile countries, through conflict-sensitive aid and trade.