Prime Minister Theresa May's visit to China this week is a timely opportunity to promote a vision of a ‘global Britain’. But as the UK’s relationship with China becomes increasingly important, ‘global’ must not only mean bolstering trade links but also considering the humanitarian and conflict implications of the relationship. Here are three points she should be mindful of before arriving in Beijing:

- Focusing solely on trade undermines the UK’s reputation as a leader in humanitarian response

This visit is an important opportunity to ensure that any trade deals which advance the UK’s economic interests will not be made at the expense of its humanitarian values.

The UK’s reputation as a global humanitarian leader risks being undermined by other foreign policy priorities such as trade and migration. The decision to sell UK arms to Saudi Arabia which is a belligerent in the Yemen conflict, for instance, demonstrates the damage that prioritising trade can do to the UK’s moral leadership. The UK’s perceived role as facilitating the devastation in Yemen makes it harder for the UK to argue in the UN Security Council or with warring parties for humanitarian access elsewhere.

The opportunities for enhancing trade links are, of course, significant. But deals with China need to be scrutinized through this lens to avoid long-term harm to the UK’s reputation. Any decision to invest and participate in Chinese projects in countries such as Myanmar or Sudan could make economic sense for UK businesses but come with high reputational risk. Especially if those projects are seen to provoke conflict or displace people due to resource extraction or construction.

- Collaborating on ‘One Belt, One Road’ can be a win-win based on UK expertise in fragile countries

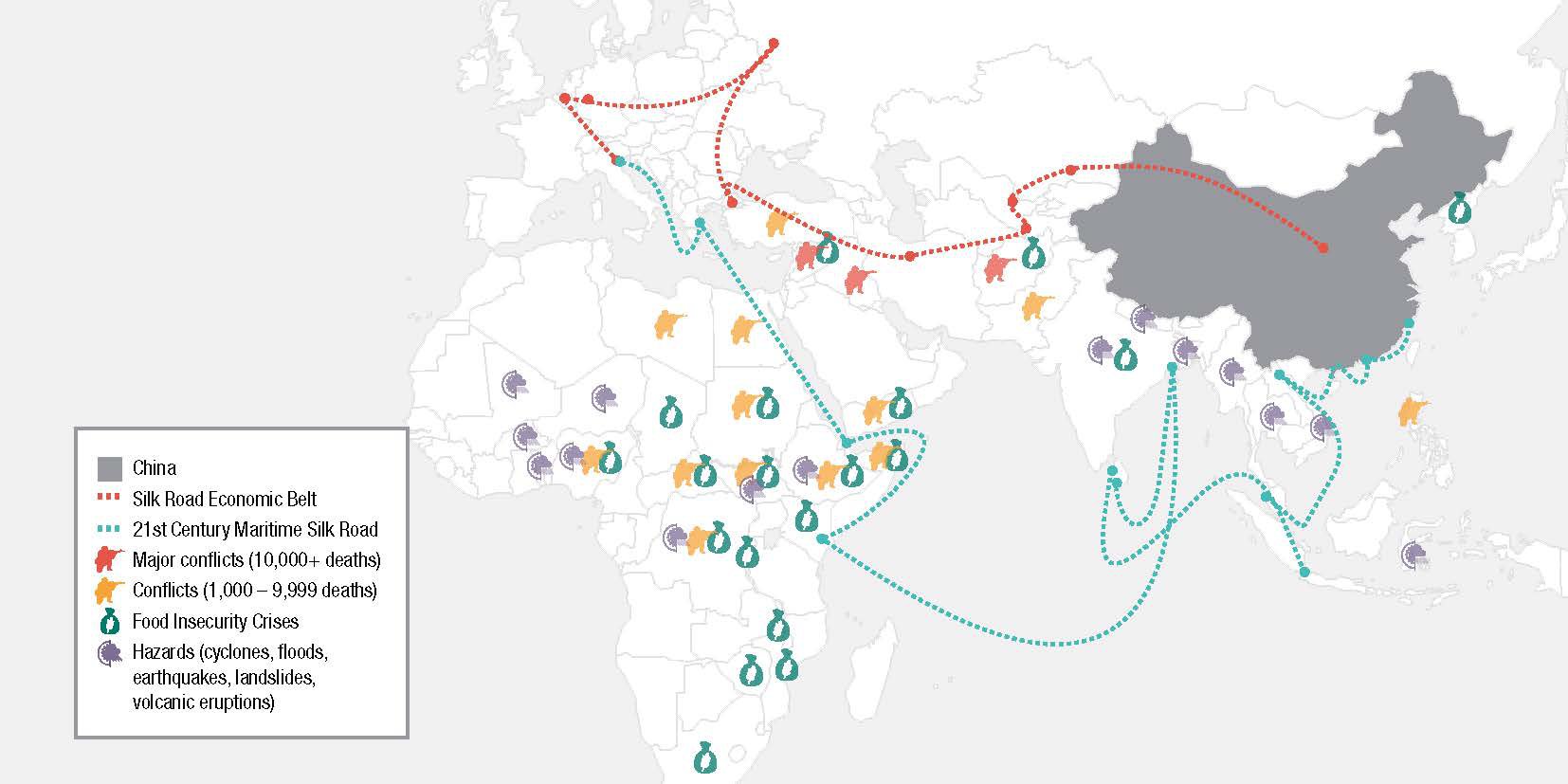

The UK is well-placed to play an integral role in supporting China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative through its position as a global financial and legal centre, and through the involvement of UK firms in infrastructure projects. But there are also important shared interests in exchanging expertise on the risks of operating in the many turbulent regions through which the Belt and Road operates.

President Xi’s ambition to implement his Silk Road vision could make fragile situations worse if insufficient attention is paid to conflict risks. Of particular concern is China’s investment in energy and infrastructure in many turbulent regions in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, which are part of or neighbour the Belt and Road. China is increasingly anxious about the risks to its investments and reputation from the failure of its projects in fragile countries.

In Pakistan for example, China’s investment in oil and gas pipelines and port construction in Balochistan province have been threatened by separatist groups who protest that the economic benefits will be diverted from the local area. While in South Sudan, China’s investment in the oil industry has been continuously disrupted by the ongoing civil war.

The UK can offer China significant expertise in combining aid and trade approaches that manage such risks in a responsible and conflict-sensitive way. Its long-term engagement in Pakistan, South Sudan and other fragile countries both through the UK Aid programme and its business ties are valuable experiences for our relationship with China and its businesses. The UK’s deep understanding of these country contexts creates an opportunity to offer conflict-sensitive finance and risk management approaches that align with China’s burgeoning Belt and Road ambitions.

- China and the UK have more humanitarian values in common than you might think

In addition to pursuing conflict-sensitive trade deals, I urge the UK to be bold in engaging with China on our two countries’ shared priorities to meet the humanitarian needs of these fragile countries and others such as Syria.

China – like the UK – has a long tradition of responding to humanitarian needs for their own sake, driven by a sense of solidarity with people affected by crisis. Contrary to popular perceptions, China is just as interested in being a responsible humanitarian power as it is in enhancing its economic interests, global image and prestige, and continues to increase its humanitarian footprint across the globe.

While the UK and China may sometimes differ in their diplomatic approach to resolving the world’s conflicts, both countries have shared interests in peace, stability and mitigating the humanitarian impacts of crises on people caught in conflict.

As the UK prepares for its economic future ahead of departure from the EU, now is the time to enhance cooperation with China in these areas – building on our respective strengths and recognising diverse approaches – to promote a ‘global Britain’ of benefit to the UK, China and affected communities.