This past week has seen new poverty estimates and projections from the World Bank (PovcalNet), UNDP, and ODI. This is on top of existing estimates from the Gates Foundation and Brookings.

The estimates broadly agree on the big picture. Extreme poverty is declining. But that decline is slowing, and many people who are already vulnerable risk being left behind even further. On the current trajectory, we will not eradicate extreme poverty by 2030; we will not even reduce it to the revised target of 3%.

How the data differs

These sets of numbers are arrived at differently. The World Bank updates are based on a more recent wave of household surveys; UNDP assesses the impact of poverty using the multi-dimensional poverty index (MPI) incorporating health, education and living standards.

Meanwhile, World Poverty Lab and ODI projections are based on World Bank data – but with some deviations in the methods and assumptions when projecting. World Poverty Labs use World Bank projections for population and income/consumption, but IMF data for aggregate country growth rate projections. ODI projections adopt one of the different scenarios suggested in this World Bank report. Brookings adopts the poverty estimates from the World Poverty Lab/World Poverty Clock – itself based on World Bank data.

The tracking is usually done with two complementary indicators: proportion of people living on below $1.90 (2011 constant USD) per person per day, and the absolute number of people who live below this same threshold – in other words, the poverty headcount.

Both are needed to get the full picture: where extreme poverty is concentrated in places with high population growth, for example, declining overall poverty rates might still leave us with the same or an increasing number of poor people.

What the new numbers tell us

The good news is that regardless of the measurement definition, source or methodology, extreme poverty continues to decline.

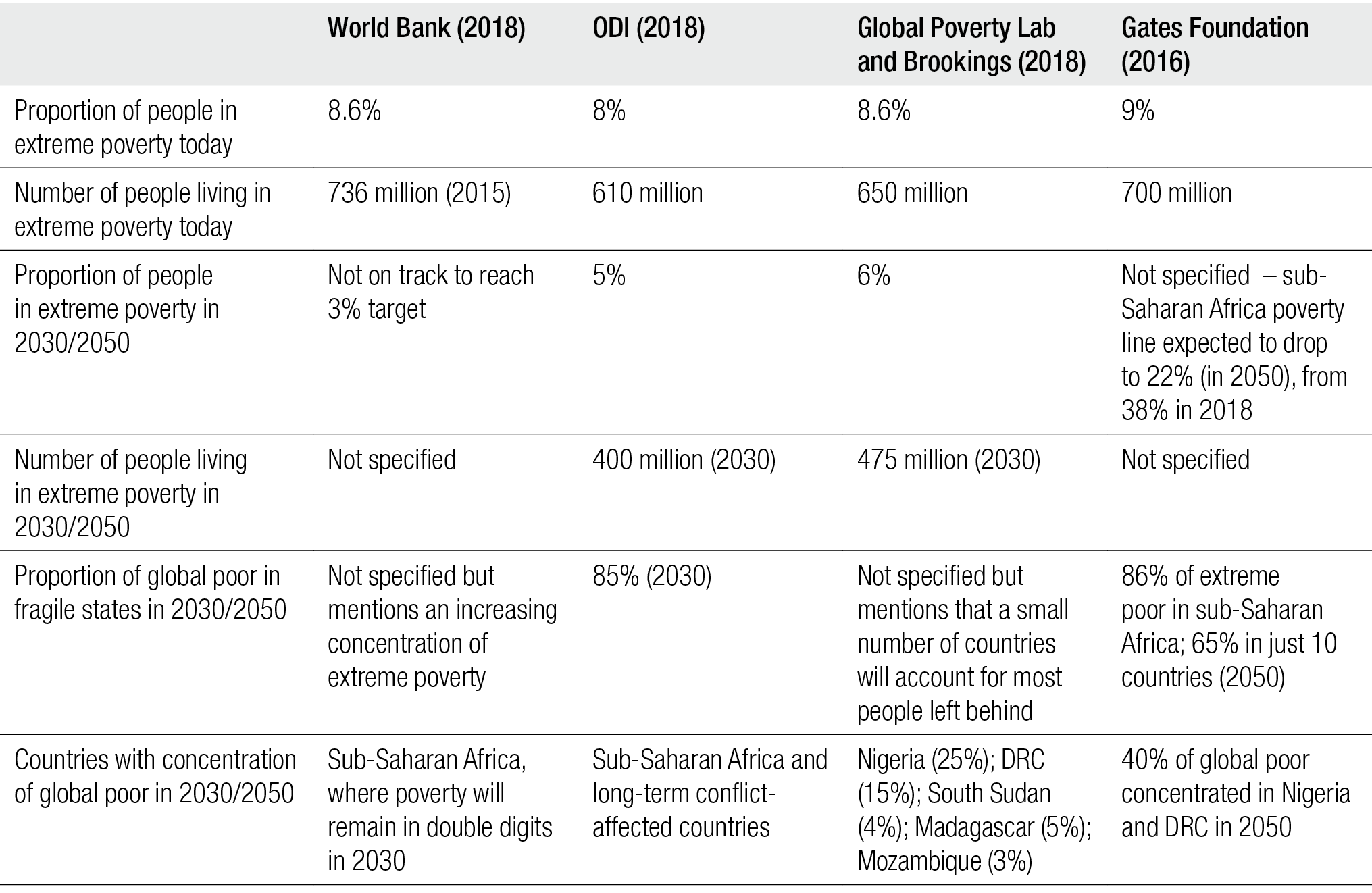

The proportion of the population in extreme poverty has fallen from 36% in 1990 to 8.6% in 2018 (8% by ODI estimates). Similarly, the poverty headcount has fallen from nearly 1.9 billion in 1990 to about 610-650 million in 2018.

This table omits the UNDP estimates as the units of assessment are not directly comparable – they are not population estimates based on income/consumption.

And the bad news? The rate of poverty reduction is slowing down. The decline in poverty was more than one percentage point per year; it has tapered to less than half that rate since 2015. This is partly due to lower aggregate economic growth rates over this period – it is easier to allocate more resources to the poorest in times of sustained prosperity.

The projections also suggest that poverty – whether in terms of income/consumption or the multi-dimensional measure – will be not be evenly spread. Of 105 countries in the UNDP-MPI, the 26 countries with the highest proportion of people in severe multi-dimensional poverty are all in sub-Saharan Africa. They are also typically countries that have high income poverty and low GDP per capita (the correlation between the proportion of population in extreme poverty and multidimensional poverty is as high as 0.73). Fragile states and those with high population growth rates but low financial and other resources to distribute (such as fiscal resources from tax revenue) will be more affected, as a new ODI-IRC report due out later today will show.

Within countries, children and adolescents will form a disproportionate number of the extremely poor. This jeopardises the long-term productive capacity of the future workforce – not to mention the failure to provide basic human needs, and conditions for dignity, peace, and social cohesion.

Implications for Sustainable Development Goal target 1.1 to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030

A few years ago, estimates suggested that the existing trajectory might be enough to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030. The World Bank revised its target in 2015-2016 to acknowledge that reaching the very poorest person would be exponentially more expensive and difficult. The new target was to get the number of people living on under $1.90 a day down to 3% or less by 2030.

The revised estimates show we might not be able to reach even this revised target by 2030. At the current trajectory, we will still have about 6% of the global population – double the target – and about 400-475 million people below the threshold in 2030. Ravallion reports another possibility that it might take more than 250 years to eliminate poverty.

Getting back on track may require accelerating growth or more targeted redistribution and allocation of resources to those extreme poor. Or, most likely, some combination of both. The IMF’s illustrative analysis released yesterday in select countries on the cost of achieving some of the Sustainable Development Goals highlights that allocating more money to end poverty, particularly for the poorest in the poorest countries, will be vital.

UNDP's multidimensional outlook gives policy-makers more pathways for eradicating poverty, or at least mitigating the harshest impacts of extreme poverty. But the high correlation between those lacking income (and hence living standards) and those lacking health and education tells us that ending poverty has to be a sustained, cohesive, coordinated strategy. The current trajectory is proving inadequate to meet the goalposts we set for ourselves.