The World Bank’s recent release of its updated poverty numbers for 2015 reveal 736 million – or 10% – of the world’s people live in extreme poverty, down from 11% in 2013.

The reduction is of course cause for celebration, though the rate of poverty reduction has slowed, suggesting that it will be challenging to eradicate it entirely by 2030.

Yet for households that escape poverty but subsequently fall back into poverty, fall into poverty for the first time, or even remain in chronic poverty, these figures mask a sombre reality.

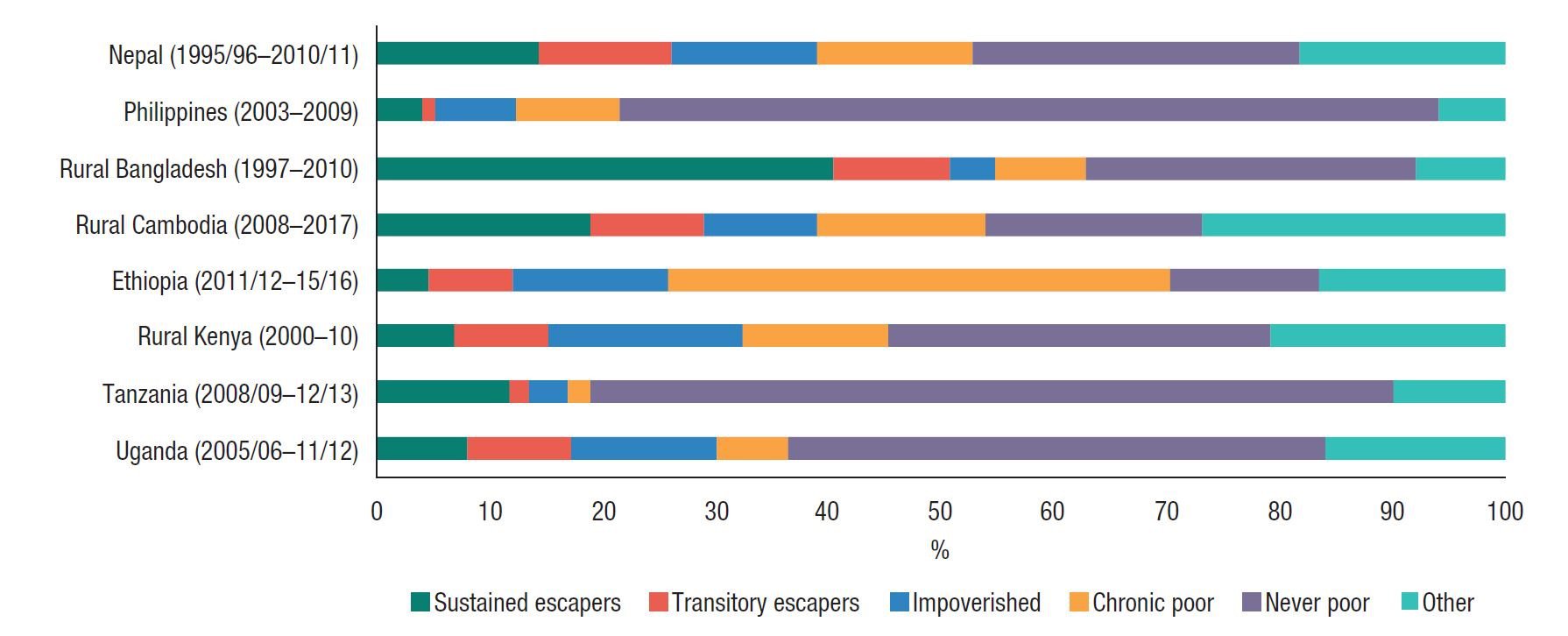

New research by the Chronic Poverty Advisory Network indicates that sustaining an escape from poverty doesn’t happen for most of the global poor. Instead, in eight countries in Africa and Asia, ‘poverty mobility’ was the norm.

Note: trajectories are based on national poverty lines which are not always strictly comparable.

In some countries like the Philippines, the share of sustained escapes rivalled that of households escaping but then falling back into poverty (a transitory poverty escape).

In rural Kenya it was also common for households to become newly impoverished, or remain immersed in chronic poverty as observed more recently in Ethiopia.

Why people fall (back) into poverty, and how governments can help sustain escapes

What’s preventing people escaping poverty for good? This is exactly the question governments need to address, and it varies from country to country.

In Nepal, for example, social and gender-based norms harm people’s chances of sustaining an escape from poverty by stopping vulnerable groups from fully participating in economic and political life. Anti-discrimination measures can help reduce this risk.

Ill health is a more universal issue. Rwanda’s health insurance programme – which now has over 80% coverage – is helping to contain this risk, improving the quality of the country’s health services, making contributing premiums compulsory, and subsidising the premiums of the poorest people.

Other countries are now starting to emulate this programme (although they will find it a hard example to follow because Rwanda’s politics are distinctive).

In agriculture the picture varies more widely, but there are multiple risks throughout the production and marketing process, from an unpredictable climate to unreliable markets.

Measures that can help include investing in irrigation; farming systems that conserve water and develop soil fertility; and market systems which have a degree of built-in reliability and predictability.

In some places such as Kenya there are schemes to pilot insurance on a small scale, and there are a number of larger-scale schemes – as in India.

But mostly, these widespread and growing risks are unprotected.

The bottom line: prevent risks, nurture enablers

Poverty aggregates like those published by the World Bank provide an initial static profile of how many people are poor.

But to speed up the rate of poverty reduction and get closer to the goal of eradicating it by 2030, policymakers, non-governmental organisations, practitioners and other stakeholders need to identify these risks in their national and subnational contexts and devise policies aimed at reducing them.

This is especially true in sub-Saharan Africa, where transitory escapes and impoverishment exceed the rate of sustained escapes.

For example, in Ethiopia between 2011 and 2016, for every nine households that fell into poverty or only temporarily escaped it, just two managed to escape and stay out of poverty over the long term.

This is mainly fuelled by the major risks of recurrent drought and also ill health. Of countries we have investigated in Africa, only in Tanzania is this ratio reversed – possibly because it has a lower national poverty line than the other countries.

People use many different strategies to earn a living and escape poverty.

Governments need a sounder understanding of how economic growth, progressive social change and an inclusive political and policy environment can enable more of them to succeed – and how risks like ill health, discrimination, crime, conflict and climate instability harms their chances.

Among elites where the narrative around poor people ‘lifting themselves up by their bootstraps’ and a reluctance to create ‘dependencies’ prevail, this message clearly isn’t getting through.

In other cases, decision-makers may simply be reluctant to divert public expenditure from more attractive priorities – infrastructure, education, industrialisation.

But looking closely at the data makes one thing clear: without determined action to help people permanently escape poverty, even the World Bank’s revised poverty projections look optimistic.