The Minister for Women and Equalities, Penny Mordaunt MP, has just announced new support for the economic advancement of low-paid and ‘hard to reach’ women in the United Kingdom.

This is a significant step, as it will further the UK’s domestic progress on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5, which aims to achieve universal gender equality and women’s empowerment by 2030.

Wearing her other hat – that of Secretary of State for International Development – Mordaunt is of course also responsible for the UK government’s support to the poorest and most marginalised women in low-income countries.

This dual mandate offers unprecedented promise to invigorate cross-government efforts and further ramp up support for the economic rights of left-behind women globally – an opportunity not to be missed.

What it means to leave no one behind

Leaving no one behind means deliberately targeting policies, programmes and funding to improve the lives of society’s poorest, most excluded and most discriminated-against people.

Our new report, developed in partnership with Age International, finds that older women are economically marginalised across the world: a perfect example of a group that UK support should focus on.

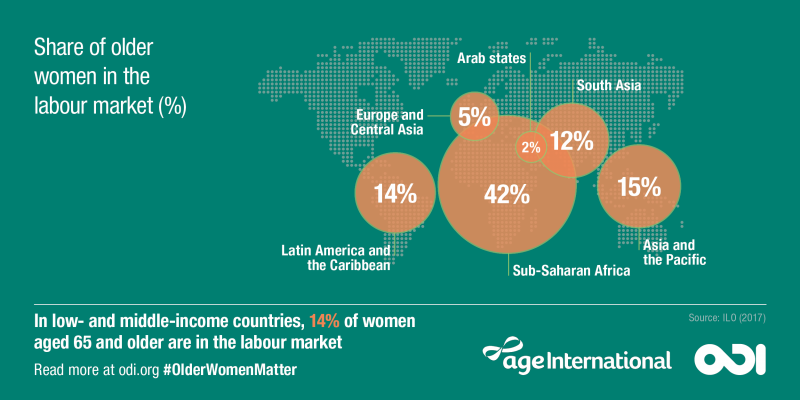

Our evidence is clear. Across lower and middle-income countries at least 1 in 7 older women is in the labour force – rising to more than 4 in 10 women in sub-Saharan Africa.

Critically, these women are disproportionately working in the lowest-quality, lowest-paid roles in the informal economy and agricultural sector.

It’s not just about the paid labour market. Across 30 countries, older women carried out over four hours of unpaid care work daily – rising to seven hours in Cape Verde. This means that older women take on over twice as much unpaid care work, on average, as men.

This work sustains the labour force and contributes to the human development of children and others in their care. In short, this largely unrecognised labour has intrinsic value to economies and societies – but women are often the last ones to benefit.

Unavoidable, unpaid care commitments can limit women’s entry into better quality paid work. And time spent not in paid work while bringing up children too often limits women’s access to contributory pensions – leaving them economically vulnerable in later life.

But there is another way. Governments should include older women in economic decision-making; fully account for them in public budgets; guarantee decent work and social protection; and support the redistribution of care in households and through quality public services.

Time to act

There are at least four good reasons for the British government to go further to ensure older women are not left behind in the UK or globally – and why Mordaunt is ideally placed to lead the charge.

First, our research clearly shows the full realisation of older women’s economic rights is a long way off, meaning politicians leading government gender equality efforts have a duty to address gaps without delay.

Second, the UK government has committed to the SDGs – a global agenda with women’s economic empowerment and ‘leaving no one behind’ at its core. As recognised (pdf) by a key parliamentary select committee, for too long the UK government has seen the SDGs as something to help other countries, instead of learning from experience elsewhere to implement the goals at home.

But Penny Mordaunt’s multiple-ministerial role provides real scope to instigate a joined-up UK government approach to gender equality, maximising Global Britain’s cross-departmental collaboration and policy coherence to benefit women, societies and economies – both at home and away.

Third, the scale of the challenge is enormous; substantial, dedicated funding is a prerequisite for success. The case for resourcing women’s economic empowerment is clear: recent analysis demonstrates that public investment in care infrastructure not only goes a long way towards gender equality, but stimulates job creation and economic growth in OECD and emerging economies alike.

Public investment in care infrastructure not only goes a long way towards gender equality, but stimulates job creation and economic growth in OECD and emerging economies alike.Although the £600,000 just announced to help marginalised women in the UK into work is welcome, it is a drop in the ocean.

Further afield, data (pdf) confirms that donor spending in low-income countries – including that by the UK’s Department for International Development – remains woefully inadequate to meet current commitments to women’s economic rights and empowerment.

With a legal duty to promote gender equality and accompanying commitment to spend 0.7% of the UK’s gross national income on overseas aid, coupled with the prime minister announcing the ‘end of austerity’ at home, the moment is ripe for Penny Mordaunt to fill the UK’s funding gap.

Finally, the spotlight will be on the UK in 2019. United Nations member states will make new commitments to social protection and review progress on the SDG gender agenda at the Commission on the Status of Women in March. And the UK’s Voluntary National Review on overall SDG progress is underway, with a report due to the UN by July.

As a chief emissary on both gender and development, Mordaunt will need to demonstrate the UK government can turn talk on the global stage into concrete action, following her predecessors’ leading roles in the development of the SDGs and on the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment.

Leaving no one behind is the order of the day. Raising the bar further on the economic rights and empowerment of older women can make this aspirational agenda a reality before 2030.