As the UK approached its Brexit deadline in March 2019, our experts provided rolling commentary on the likely economic impact on low- and middle-income countries.

Use a Brexit extension to develop the UK’s long-term trade and development agenda

Dirk Willem te Velde, 9 April 2019

Decisions on Brexit are taking longer than originally envisaged – but this could be a good thing.

We don’t yet know when a withdrawal agreement will be agreed, if at all, let alone what the future UK–EU relationship may hold. So let’s cut through the short-term complexity and shift attention to long-term trade and development strategies. For example, low- and middle-income countries could take the long view, as expressed by South Africa’s trade and industry minister.

The UK could also use this extension to develop a stronger trade and development agenda. Instead of pushing long-term issues aside in favour of short-term ‘no deal’ preparations, the government should now target five trade and development areas that will be important regardless of the shape of negotiations:

1. Short term fire-fighting, with a long-term strategy in mind

The UK should ensure existing EU free trade agreements are rolled over comprehensively to maintain UK market access for low- and middle-income countries. This could include break clauses that allow for changes in UK–EU relationships.

The UK could also announce an ambitious General System of Preferences which includes preferences for the poorest countries that can apply on Day 1 (in case of a no-deal Brexit); on 1 January 2021 (in case of a deal); or which can inform reform to the EU’s preference scheme, if the UK stays in the Customs Union.

2. Develop trade in services

Even if the UK stays in the customs union, it could offer services preferences and develop long-term services agreements with countries that want them. It would be promising to develop financial and digital co-operation, as emphasised in a parliamentary report ahead of the 2018 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) report. Mobility of people is a crucial component of this too. E-commerce is an important negotiating topic in the run-up to the 12th Ministerial of the WTO in Kazakhstan in 2020, so there can be a link between bilateral and multilateral efforts.

3. Develop a UK import strategy and appoint a Director General for imports

The UK is focusing much attention to exports and outward investment. It also needs an import strategy that facilitates good quality, reliable and cheap imports of goods and services from low- and middle-income countries. This is good for exporters in those countries – and it’s good for UK consumers and processors, securing access at lower import prices. This will be important in any of the Brexit scenarios.

4. Provide effective Aid for Trade

The UK could continue its successful Aid for Trade programme in a couple of ways. First, it should step up support for African continental integration by helping to connect countries through physical, regulatory and digital measures. Second, it should support countries – especially those poorer Asian countries that will soon be reaching development thresholds which means they may not be eligible for trade preferences. Aid for Trade could be provided in coordination with other agencies (such as CDC, the UK's development finance institution) to help build markets.

5. Facilitate long-term investment

The UK is due to host an Africa Investment Summit in early 2020 and is Commonwealth Chair until the 2020 CHOGM in Rwanda. Both are ideal opportunities to facilitate private long-term investment into the poorest countries.

Several short-term trade issues still need urgent attention, but the UK should use a Brexit extension to shift capacity to longer-term trade and development issues that need attention – whatever direction Brexit negotiations may take.

Poorer countries should keep focusing on the long-term trade agenda

Dirk Willem te Velde, 25 March 2019

As the current impasse in parliament continues, a number of Brexit options remain on the table. Many poorer countries still do not know exactly what terms and conditions their exports will soon face in the UK.

If the UK leaves the EU without a deal on 12 April 2019, there could be severe consequences for development, including a halving of the value of preferences. The UK has signed a number of continuity agreements which try to replicate preferential access as much as possible in case of a no-deal Brexit. Agreements have been signed for four eastern and southern African countries, two Pacific countries and eight Caribbean countries.

However, West African countries such as Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire have not been covered while those in the Southern Africa Customs Union and Mozambique need more time to understand the arrangements. Secondary legislation is still required to sustain preferences for exports from least developed countries (and potentially other vulnerable countries), which there wouldn’t be time to pass.

If the UK parliament votes for Theresa May’s deal and the UK leaves the EU on 22 May 2019 then the proposed transition period until the end of 2020 would give officials in the UK and developing countries time to properly (re)consider options. These include economic partnership agreements, a new tariff schedule, use of rules of origin and standards and a new General System of Preferences that could start in 2021. Such arrangements would depend on the eventual shape of the UK–EU relationship.

Another potential scenario could see the UK remain in the current customs union and single market, which would likely mean fewer changes to developing country access in the UK than previously considered. And a referendum on Theresa May’s deal reintroduces the possibility that the UK may remain in the EU, which would put developing countries back where they started on their potential future trading relationship with the UK.

Don't be distracted by short-term uncertainty

But rather than second-guess the next twist in the Brexit drama, poorer countries should continue to focus on pursuing their own strong trade and development agenda and not be distracted by short term uncertainty. And any trade deal provisionally agreed between the UK and developing countries probably needs revision once the UK–EU relationship has become clearer.

In the long run the trend will be towards less preferential access for their goods exports to the UK. Significant new opportunities for trade and growth lie closer to home. Africa, for example, is one country’s signature away from the launch of the operational phase of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), with 21 out of the 22 signatories required.

https://twitter.com/AmbMuchanga/status/1108743840263897088

Least developed countries such as Cambodia need to be focusing on increased competitiveness in a world without (UK) preferences anyway as they are scheduled to graduate. Meanwhile, Caribbean and Pacific nations could increasingly move into the digital economy, which depends less on goods preferences.

The economic costs of a no-deal Brexit for the poorest countries

Dirk Willem te Velde,13 March 2019

The government forecasts large economic costs of a no-deal Brexit. The Bank of England expects a 25% devaluation in the pound and an 8% drop in GDP compared to ‘current levels’.

A no-deal Brexit will also affect poorer countries, due to the impact it could have on trade deals between the UK and low- and middle-income countries, the UK’s general import regime and through weakened UK performance. Overall, ODI estimates that the costs to the poorest countries could be as much as $60 billion (the sum of the effects discussed below) if the UK leaves the EU without a deal.

Here are three ways we believe a no-deal Brexit could significantly impact developing countries, and what the UK should be thinking about to avoid negative effects.

UK imports of goods in case of no-deal Brexit

The UK has announced it will impose zero tariffs on the majority of imports in the event of a no-deal Brexit. If this happens, countries that currently have zero tariffs for the UK could see these benefits eroded as they suddenly come into direct competition with every other country in the world. Our figures suggest this could halve the value of tariff preferences which would cost developing countries £0.9 billion (based on 2013-2015 data using current exchange rates). In Africa, this would mean a fall in the value of preferences from £318 million ($407 million) to £181 million ($232 million).

At the same time, UK import demand would decrease due to the projected 8% drop in UK incomes and a 25% devaluation in the pound, making imports more expensive. ODI estimates the total decrease in UK goods imports from all 127 preference-receiving developing countries is worth $25.1 billion*.

UK imports of services in case of no-deal Brexit

A 25% devaluation in the pound will make holidays abroad 25% more expensive for UK residents. This could have a significant impact on overseas tourism. UK imports of tourism services from Africa are worth £1.7 billion ($2.2 billion). Overall, we estimate a drop in demand from UK tourists visiting Africa could see the continent lose as much as £792mn ($1013mn)**.

UK imports of services from non-OECD countries in 2015 amounted to $54.1 billion, including $6.8 billion from Africa. Extending the above calculations to all non-OECD countries, UK services imports would fall by $25.2 billion.

Aid and remittances in case of a no-deal Brexit

The devaluation in the pound will also affect the value of the aid the UK provides to developing countries. In 2017 this amounted to £13.9 billion, or $17.8 billion. A 25% devaluation would buy $4.4 billion fewer goods and services in developing countries. In addition, the commitment to a fixed proportion of GNI on aid means that an an 8% decrease in UK income would be matched by an 8% decrease in aid, which would amount to to $1.1 billion. Furthermore, UK remittances abroad were £9.7 billion. Again, a 25% devaluation in the pound means this amount of remittances buys fewer goods and services globally, to the tune of $3.1 billion. The combination of reduced remittances and aid would amount to $5.5 billion ($4.4 billion + $1.1 billion) less for developing countries.

While this is admittedly based on some strong assumptions, what it shows is that a no-deal Brexit could have potentially damaging consequences, not just for the UK but also for poorer countries. As the government continues its ambition for a ‘Global Britain’, these consequences need to be addressed. The uncertainty alone, created by the prospect of no deal hanging over negotiations, is having an impact on the poorest countries as they decide how best to proceed in their political and economic relationships.

*ODI's analysis assuming a price elasticity of minus one and an income elasticity of one.

** ODI's analysis assuming a price elasticity of -1.2 and an income elasticity is 2.2.

New UK tariff schedule will hit poorer countries preferences

Maximiliano Mendez-Parra,13 March 2019

In the wake of the Commons defeat for Theresa May’s Brexit deal last night, the UK has announced a new temporary tariff schedule in the event of a no-deal Brexit. The schedule suggests that 87% of the products imported in the UK, regardless of the origin, will face a zero tariff.

This may provide a tiny relief for consumers - a quick overview suggests that the products whose tariff is reduced represent around 13% of total household expenditure in the UK* - however, the new UK tariff will have a serious effect on the value of preferences provided to poorer countries.

Many low and middle-income countries export to the UK duty free, either because they have free trade agreements (FTAs) with the EU or because they receive unilateral preferences.

The benefit they receive is the difference between what non-preferential partners, such as the US, pay and the tariff paid by those with preferences. For low and middle-income countries with preferential access, this is around £1.8 billion in savings. This represents how much developing countries save in terms of duties when exporting to the UK.

However, the new UK tariff schedule would reduce the value of this benefit to £910 million, meaning developing countries will lose half the value of their preferences as zero tariffs are extended to all.

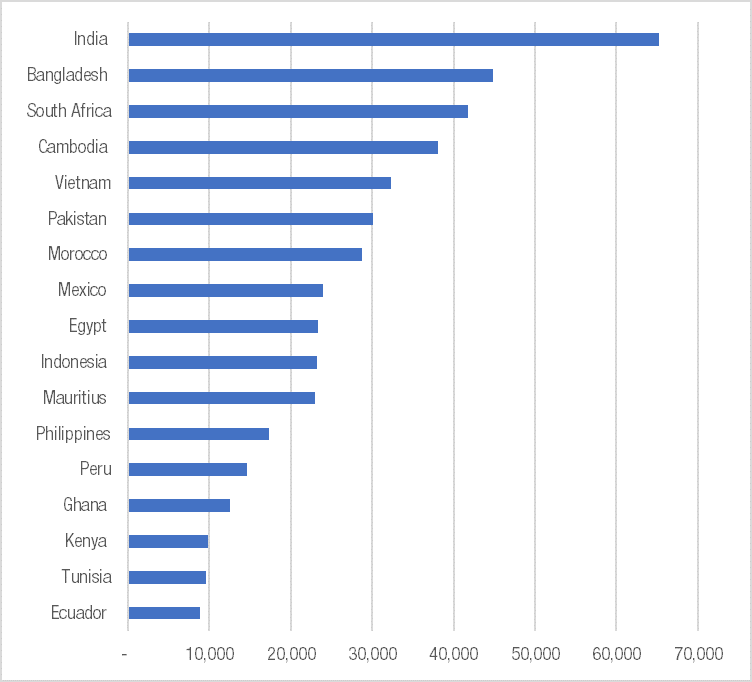

Loss in value of preferential access to the UK (in thousands of pounds)

Source: own elaboration based on EU Comext database.

If we look at some of the specific sectors we can see how certain countries are going to fare worse from the new regime than others.

On garments, while not all products will be affected, many will have zero tariffs under the proposed schedule. This will have a particularly damaging impact on Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Mauritius and Pakistan. Footwear will also fall to zero, severely impacting the value of preferences of Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia. The tariff for processed fish will fall, affecting Ecuador, Ghana, Mauritius, Philippines and Vietnam. Exports of bicycles from Bangladesh, Cambodia and Tunisia will also be affected, while Kenya will suffer because of the tariff reduction on cut roses.

South Africa, a country that agreed to roll over its FTA with the EU to the UK, will suffer due to the tariff reduction on fresh grapes, plums, clementines and wine. One wonders whether South Africa would have so easily agreed to roll over its FTA with the UK if it had known tariffs were going to be reduced for all regardless.

The problem only adds to the ongoing issue around whether the UK government will extend the preferential regime applied under the EU after Brexit, as we have previously highlighted. If preferences are not rolled over, it could mean low and middle-income countries currently enjoying zero tariffs will have to pay duty on many products whose tariffs would not be reduced under the new schedule.

The UK government must do two things. It must still roll over the current preferential regime to poorer countries so that they are protected from any rise in duty. At the same time, the UK must revise the list of products whose tariff is going to be reduced to zero to make sure the value of the preferences given to developing countries is not eroded. This would mean limiting the level of tariff reductions for some products that were announced today to protect preferential access for the poorest countries.

*Own calculation based on the computation of items in 2018’s household expenditure.