With the number of people living in extreme poverty forecast to rise in sub-Saharan Africa and declining aid and external investment flows to that region, donors need to better understand the potential of investing their aid to mobilise private investment (known as ‘blended finance’) and the impact this has on the eradication of extreme poverty.

Based on findings from my new report, I unpack the key issues donors should consider when deciding how much aid to invest in blended finance and how best to do it.

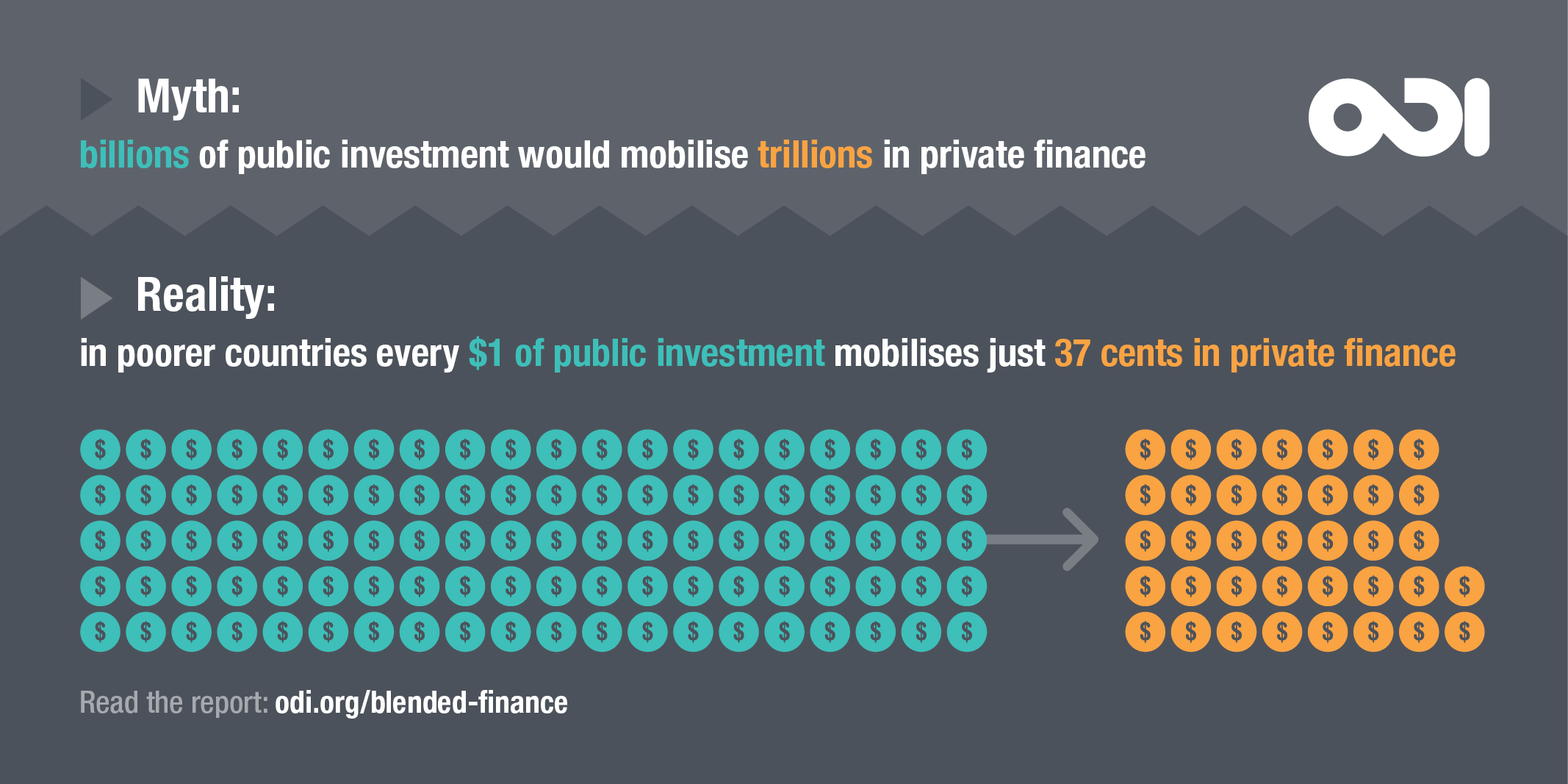

‘Billions-to-trillions’ is a myth

Donors argue that by investing aid in blended finance, they can mobilise or ‘leverage’ many more multiples of private finance for investment in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which would not happen otherwise.

The reality is very different. While it does leverage additional private investment, the sums are not huge. On average, one dollar of public investment from multilateral development banks (MDBs) and bilateral development finance institutions (DFIs) mobilises just 75 cents of private investment in low- and middle-income countries. This falls to 37 cents in low-income countries (LICs).

Clearly this approach is not mobilising significant resources. The much-hyped talk around the potential of blended finance to shift the financing needle ‘from billions to trillions’ is clouding decision-making about how best to invest in aid. Donors should have more realistic expectations about how much private money they can mobilise this way.

There's little evidence that blended finance reduces extreme poverty

The future challenge is clear: focus on eradicating extreme poverty in Africa to stand a chance of achieving SDG 1. Donors also face tough choices on how best to invest their aid. Aid is a precious and unique resource – it flows into health and education in poor and fragile countries where private finance does not naturally flow, so there is an opportunity cost when donors invest their aid in blended finance.

Trying harder to increase blended finance in LICs will most likely become more expensive, not less. There simply isn’t an abundance of investable opportunities in LICs and they can’t be magicked up overnight. MDBs and DFIs will be chasing fewer and fewer investable opportunities and investing in more marginal investment opportunities, requiring larger subsidies to encourage the private sector to co-invest.

Worryingly, there is very limited evidence out there that blended finance reduces extreme poverty. I’m not saying investing aid in this way doesn’t have an impact, but it hasn’t been the subject of extensive study and evaluation. We need to see increased efforts to improve understanding of impact and value for money to actively target poverty in blended finance decision-making.

Three ways donors can better mobilise private finance in the poorest countries

If donors continue to choose to invest more aid in this way, MDBs and DFIs need to get better at mobilising private finance in the poorest countries. How? Make better use of the aid provided to them, use a more diversified set of financial instruments, and better construct solutions for small-scale investment in LICs.

There are three areas where I think MDBs and DFIs could make more effective use of the aid provided to them:

- A greater proportion of the aid could be used in LICs rather than in upper middle-income countries (UMICs), where there is less need for a subsidy and where near market-term finance funded by the MDBs’ and DFIs’ own balance sheets is more likely to be more appropriate.

- MDBs and DFIs could use this aid to help invest in the riskiest parts of the capital structure of the investment in the poorest countries, where the private sector is unlikely to invest on its own. They can do this by making more use of subordinate instruments (instruments that rank lower in priority than other claims if the investment fails) such as subordinated debt and junior equity.

- Given the scarcity of investable opportunities, a greater proportion of the aid could be used to fund project preparation and early-stage project development, for example by making more use of grant funding.

The clock is ticking. Donors need to keep their eye on the ball to make sure that blended finance delivers for LICs and doesn’t end up diverting aid away from its core agenda of helping eradicate extreme poverty in the poorest countries.