Last week I attended the United Nations High Level Dialogue on Financing for Development, where world leaders took stock of progress since they agreed the Sustainable Development Goals and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) on Financing for Development (FfD) four years ago.

There is no escaping the scale of the challenge. ODI’s own research, launched at the Dialogue, suggests that 430 million people will still be living in extreme poverty by 2030 – the date at which the SDGs promise extreme poverty will be ended. Soberingly, this is 30 million more than we forecast last year, driven by worsening prospects for the very poorest countries.

The UN’s own report on SDG progress, released in July, says that, despite headway on some SDGs, ‘monumental challenges’ remain. Hunger, for example, is going in the wrong direction, with 821 million people undernourished in 2017, up from 784 million in 2015.

The FfD agenda is complicated, but can be boiled down to three big questions.

Mobilising public finance

First, can we mobilise enough public finance, spend it well and direct it to SDG investments that individuals and the private sector can’t or won’t pay for? ODI’s report Financing the end of extreme poverty finds that most countries could afford the public investments needed to provide universal healthcare, education and social protection if they allocated enough of their budgets to these goals –and raised more in tax (though this may not be an easy ask, which I’ll come to later).

Forty six countries can’t afford these investments on their own, but if donors met the UN commitment to give 0.7% of their income as aid, this could provide the missing money, if well targeted. There are growing calls for the UN to take public financing gaps more seriously, particularly as, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), more than two out of five low-income countries are at high risk of debt crises, and may therefore find their spending plans seriously undermined.

Shifting private investment patterns

Second, can we shift private investment and consumption patterns so that developing countries grow sustainably and inclusively and the global economy moves rapidly to become zero carbon and protect the natural world on which we all depend?

Here the FfD debate has been side-tracked by a focus among many international institutions and rich countries on the smaller sub-issue of how to use public support or subsidies to leverage more private finance (often, as shown by the statements at the Dialogue by the EU and the US, tying this to their own companies and initiatives).

ODI research finds that on average every dollar of investment through the development finance institutions that are the focus of this agenda leverages only 75 cents of private investment, falling to 37 cents in low-income countries. Clearly, this is not the magic bullet it is sometimes presented as.

Sharing economic gains

Third, can we alter global, regional and national economic structures to share the distribution of the enormous economic gains humanity has made more fairly so that everyone has enough to live well, and those at the top take a smaller slice of the pie?

This issue was emphasised by the G77 group of developing countries in their statement to the Dialogue, which pointed to areas where the international system does not work well, including illicit financial flows and tax evasion.

Just before the Dialogue, the IMF and Copenhagen University warned that 40% of global foreign direct investment – some $15 trillion – is ‘phantom’, meaning it passes through corporate shell companies often set up to minimise the tax bills of multinationals.

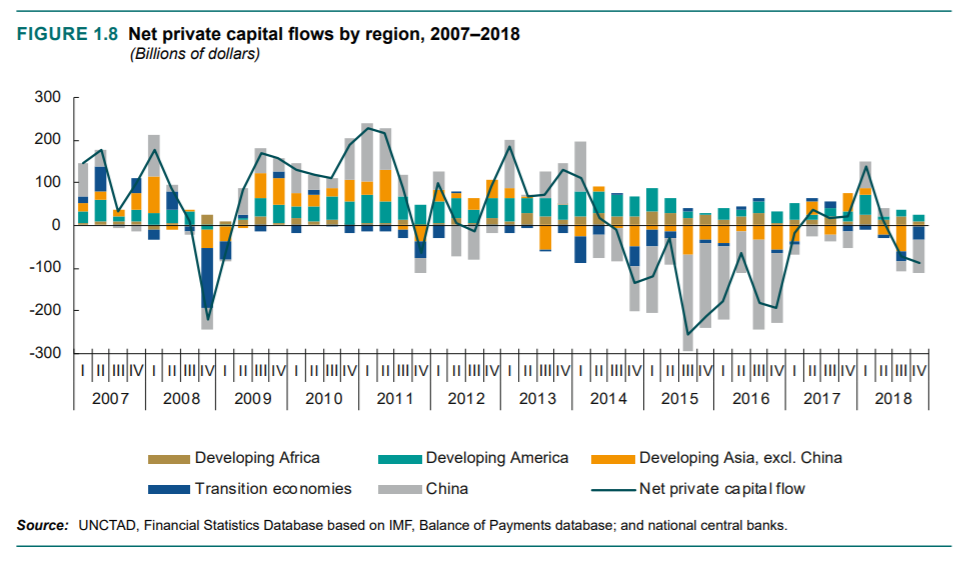

This is part of a broader problem inherent in an international system that does not provide developing countries with enough of the kind of long-term capital investments they need. For example, UNCTAD’s new Trade and development report highlights that international private capital proves consistently volatile, and was in fact a net outflow for developing countries in 2018, as the chart shows.

As is normal at these gatherings, a large number of side initiatives were launched or highlighted at the Dialogue, but, while many are welcome, they cannot replace coordinated action by UN member states together. However, there were no agreed concrete outcomes from the Dialogue itself, and governments have yet to use the annual FfD forums as a mechanism for changing course now it is clear we are way off track to finance the SDGs.

To get world leaders to take this critical issue more seriously, there are calls for a new leaders summit on FfD in 2022 (20 years after the first). Without a renewed push like this to put the issue of financing the SDGs back at the top of the global agenda, and tackle the difficult questions highlighted here, it looks increasingly likely that the world will fail to meet the SDGs, and by an increasingly wide margin.