The Covid-19 pandemic has led to an education emergency of unprecedented scale, with some one billion students and youth across the planet affected by school and university closures. The depth and duration of disruption that these learners will experience is still unknown.

However, long before the pandemic, nearly 75 million children and adolescents were already facing severe and often lengthy education disruptions due to conflict and crisis. This includes some 7.1 million refugee children of school going age.

The scale of emergency for learners who have been forcibly displaced, and particularly refugees, is often the most critical.

Following World Refugee Day and in anticipation of an event on Elevating Education in Emergencies, our experts have produced a framing paper highlighting the importance of coordination’s contribution to stronger education outcomes for children and youth affected by crises.

This work draws on recent research, including a series of country case studies in Bangladesh, Chad, DRC, Iraq, Ethiopia and Syria, produced in partnership with the Global Education Cluster, the Inter-Agency Network on Education in Emergencies and the UN Refugee Agency, and supported through Education Cannot Wait (ECW).

Frequently asked questions

Susan Nicolai: using evidence to strengthen education planning and response

If brief disruptions to education can be difficult, extended interruption inevitably has significant and often severe long-term detrimental effects to a child’s learning outcomes, well-being, and their lifelong chances.

Unfortunately, in a context of chronic underfunding, ensuring education is available to those affected by crises has not been possible. While national governments are responsible for fulfilling the right to education, including for refugees, their capacity is often constrained.

In response, multiple actors are involved in supporting education in emergencies, protracted crises, and in situations of fragility.

In recent ODI research, we explored how at a country level humanitarian and development actors can more effectively coordinate planning and response to strengthen education outcomes. Our global analysis framework set out a conceptual framework exploring coordination approaches, ways of working, and contributions to impact.

Through six country case studies, we then examined in practice how formal coordination mechanisms such as Education Clusters, Refugee Education Working Groups, and Local Education Groups (LEGs), among others, engage with national actors and each other to strengthen education outcomes.

Our overall findings point toward four main conclusions.

1. Coordination can play a critical role in minimising education disruption

Formal coordination mechanisms can strengthen results through close work with national leadership, including both central and local capacities.

In Iraq, the number and geographical spread of education sub-clusters in all seven major areas of displacement have enabled good coverage of the response, improving education access.

In Bangladesh, amidst monsoons, crisis communication chains between camp focal points, education coordinators, teachers and parents meant that quick notification and action were possible when roofs were blown away from learning centres.

2. Joined up working must be scaled up

Case studies showed need to scale up joint working across the humanitarian programme cycle, in particular across assessment, planning and appeal processes. In DRC, coordination groups have worked together through joint needs assessments to plan and sequence responses. In Chad, checklists used with communities in education project design ensured protection concerns were addressed.

3. Predictable joint funding to support education coordination can incentivise coherence

Funding itself appears to be an important enabler of coordinated action. Education Cannot Wait's (ECW) Multi-Year Resilience Programme is now active in 10 countries It provides financing committed over several years through pooled support from multiple donors, explicitly links to planning and encourages coordination.

In Syria, through investment by Education Cannot Wait and others, the Education Dialogue Forum coordinated planning efforts and successfully reached out to other donors to facilitate further financing across both humanitarian and development actors.

4. Coordination efforts should explicitly focus on collective education outcomes

One of the most interesting findings in our research was on the potential for coordination to contribute to the collective education outcomes of access, continuity and protection.

Evidence showed, however, a need to sharpen coordination efforts on education quality, equity and gender equality, in order to holistically address education needs.

In Ethiopia, collaboration between the Ministry of Education, Regional Education Bureaus, and the Ethiopian Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs improved accreditation processes for refugee children lacking formal evidence of their schooling, increasing education continuity and refugee access to government schools.

In terms of Covid-19, coordination is clearly central to the education response. Efforts like the Global Education Coalition for Covid-19 Response are in place, and calls to ‘Build Back Better’ at country-level highligh collaborative and joined up efforts. Further focus on the larger lessons of education coordination as part of the Covid-19 recovery processes are essential to maximising impact.

Frequently asked questions

Amina Khan: improving education delivery in refugee contexts

Refugee education isn’t a typical priority for education ministries and subnational counterparts unless there is an explicit national and international level commitment by the host states to focus on it.

Of the school-aged refugee children, more than half, or around 3.7 million, are out of school. Thankfully, as a result of efforts by host states, donors, UN agencies, and national and international partners, the remaining 3.4 million children have access to primary, secondary and higher education.

Ethiopia, Chad, and the DRC have all allowed refugees access to local schools and host community children to attend camp-based schools. They have also got refugee camp schools to follow the national curricula and have aligned international development and humanitarian efforts with national education sector strategies.

However as conflicts in Africa become more protracted, national education systems in these countries will reach their absorptive capacity very quickly. Many countries are not able to cope at all.

Through our research focused on education coordination, we observed three areas of improvement needed to help better deliver education in refugee contexts at the local level.

1. Expand refugee teacher training programmes to create a new professional cadre of teachers

The lack of teachers in camps – and the lack of training for those who do teach (mainly adult refugees) – have significant impacts on learning quality.

The inclusion of refugee teachers in national and regional training programmes are the right initiatives to support and scale-up the skill level of teachers and achieve a systemic improvement in learning outcomes.

A new cadre of professionally accredited refugee teachers should join the local education system and further boost learning within areas that have both refugee and local children. Accreditation and absorption into formal teaching will also enable refugees to access dignified and gainful employment.

2. Use international funding strategically to improve refugee and host community education

The lack of national and international funding in the education sector is a clear constraint for education systems to function properly.

But more can be done with the funding that exists – such as the Education Cannot Wait-facilitated multi-year resilience programmes.

International funding could be more strategically used to help incentivise the government and other education providers to work towards uplifting the educational environment for both refugees and host communities together, fostering better social cohesion.

This is especially important in places like the Gambella region in Ethiopia, where the refugee population has become larger than the host population. Our fieldwork at the time revealed that the quality of education within the camps was better than outside them.

3. Resource leadership at the local level to coordinate refugee education

It is much easier to demonstrate leadership and coordination at the top (through plans and policies) than in local settings where the crisis is more real and coordination responsibilities fall on subnational officials.

In Ethiopia, the regional and ward level education offices were struggling to lead. The national education departmental inspectors and the primary education pedagogical inspectors in Chad and the DRC had very little resources from the state to cover basic transportation and communication costs to attend coordination meetings – let alone to lead them.

Building education coordination capacity, particularly of education officials at the local level, by funding people and strengthening capacity through training, mentoring or coaching support is crucial going forward, in these countries and elsewhere.

With global enthusiasm and investment for refugee well-being on the rise, national education systems stand a good chance of strengthening internal capacity and resourcing. This can be achieved through better trained refugee teachers, strategic use of international funding, and greater leadership in coordinating refugee education at the local level.

More importantly, by doing this, they will be providing a great service to the millions of children caught in crises, for whom education is a central need and priority.

Frequently asked questions

Vidya Diwakar: linking coordination efforts and collective education outcomes

Better coordination around education in emergencies and protracted crises can lead to strengthened outcomes, but this is not guaranteed, nor does it happen in a vacuum.

The success of coordination lies in its ability to facilitate coherent planning, connectedness and timeliness, among others, that in turn improves coverage and continuity of education.

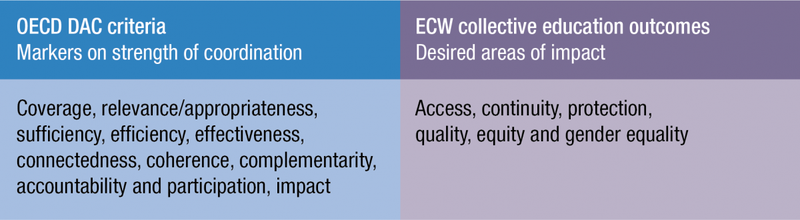

ODI research on coordinating education in crises provides evidence on these links through an innovative framework, bringing together the OECD DAC Criteria for Evaluating Development Assistance (PDF) and the Education Cannot Wait Collective Education Outcomes, as the chart below shows.

1. Focus on education outcomes of access, continuity and protection

Three key takeaways emerged in our exploration of evidence linking coordination and collective education outcomes.

Our case studies pointed to strong links from coordination to collective outcomes in terms of access, continuity, protection and quality.

For example, in Ethiopia efforts to integrate refugee enrolment data into the national Education Management Information System improved knowledge about where refugee students were enrolled. This allowed schools to be funded accordingly and contributed to education continuity.

In Iraq, the coordination of humanitarian actors enabled dissemination of humanitarian principles around better protection outcomes, including safeguarding, monitoring and mitigation of risks faced by school children.

2. Strengthen links to quality, equity and gender equality

We found less evidence linking coordination to quality, equity and gender equality, suggesting a need for concerted effort in these areas.

In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh (but also observed elsewhere), coordination around mapping has improved knowledge about attendance and out-of-school children. This has supported outreach to out-of-school boys and girls, increased access to learning, and in turn, boosted gender equality.

3. Develop synergies in coordination aided by localisation

A final takeaway is that criteria such as connectedness and timeliness create synergies which then reinforce each other in collective education outcomes including improved access to education.

In Chad, where the Education Cluster strategy was developed, working groups were formed based on relevant ‘pressing issues’, and included measuring education demand/supply and promoting governance (e.g. parents’ role, teacher attendance).

These elements reflect markers of coordination such as coverage, relevance, and accountability, aided through localisation, which in turn improve education access, quality and continuity.

This last point should be particularly encouraging for those concerned about efficiency and cost-effectiveness in improving learning outcomes.

For researchers, synergies offer avenues for further exploration on how to better strengthen equity and gender equality.

For girls and boys in emergencies and protracted crises, greater attention to coordination can lead to much-needed improvements in learning, with positive implications for both immediate and longer-term well-being.