As states confront their vulnerabilities to the coronavirus, grapple with elected populist strongmen and gingerly navigate Sino-American fault lines, principled nationalism is urgently needed.

But principled nationalism is also harder to come by.

Nowhere is this challenge felt more starkly than in the world of foreign aid.

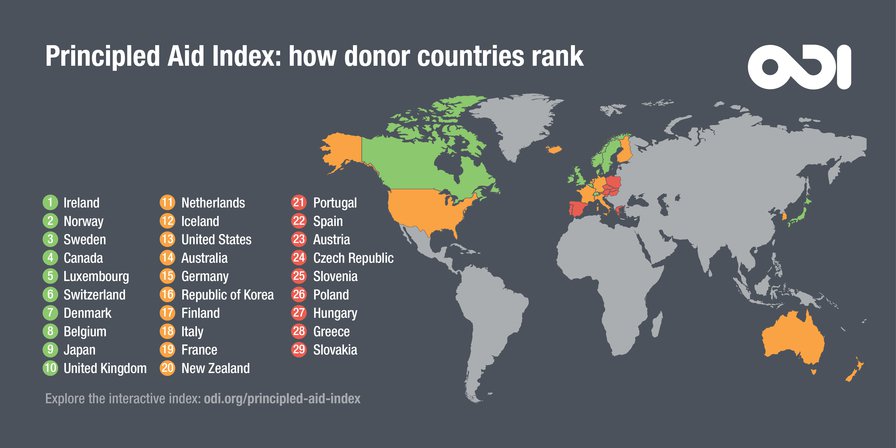

ODI's Principled Aid Index reveals bilateral donors' motives for aid-giving at a time of growing nationalism and global division. High ranking donors are working towards a more stable, secure and prosperous world from which they stand to benefit and are advancing the values of global solidarity and collective action.

Some may argue that this understanding of a principled national interest is nothing more than altruism in disguise. And yet, the pursuit of more parochial forms of nationalism will lead to collective action failures so significant they jeopardise lives and livelihoods everywhere. States are intensely connected through trade, travel and telecommunications but also share vulnerabilities to critical existential threats. This makes fixing the twin challenges of underdevelopment and ineffectual global cooperation a 'hard' strategic interest.

But it is a strategic interest that many countries have yet to fully appreciate, lofty political rhetoric aside. The results of this year's Principled Aid Index provide three reasons to be concerned.

1. Northern donors moving 'South' as principled aid falls

While there is much to be proud about Ireland ranking first on the 2020 Index, its success belies the fact that its aggregate score has fallen since 2017. This is also the case for many others at the top of the charts, including Sweden, Canada, Iceland, Denmark and Norway. While the worst-performing countries still lag significantly behind the highest-ranked ones, the gap is closing as countries like Greece, Hungary and Poland improve their scores. A focus on donor rankings misses this decline in the average principled aid score.

This finding suggests what many may have already known intuitively – that traditional stewards of good donorship like the United Kingdom can no longer be looked up to as role models. The motives of Northern donors appear to be gradually tilting towards securing narrow benefits for themselves, rather than maximising efforts towards achieving development impact.

This tilt may be partly motivated by competition from Southern providers, where the successful projection of 'win-win' narratives is used to justify overseas spending to their own sceptical citizens. At the same time, this logic also wins the diplomatic support of recipient countries. Rather than traditional donors socialising Southern providers, the reverse may be happening as aid is steered towards the achievement of narrow domestic goals under the guise of realising mutual benefits.

2. The club of wealthy countries is fracturing

The Development Assistance Committee has acted as a club of rich-world donors with a mandate to define and normatively regulate their actions. Nevertheless, fissures are now more obvious within the group on the merits of principled aid. For example, newer European donors are concentrated at the bottom of the rankings. Italy, Spain, France and Portugal have all hovered around 20th place in the last five years, while Scandinavian countries tend to do well.

The Index also finds strong and consistent performance by Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland. This may provide the foundation for a new sub-alliance to advocate for greater commitment to the tenets of principled nationalism. At the same time, motivational fissures may lie behind some of the institutional weaknesses of other diplomatic clubs. The G20 and the UN Security Council, for example, are increasingly coming up short in the fight against debilitating global challenges. Efforts to reimagine multilateralism within these 'mini-lateral' fora will need to first contend with this ebbing away of common cause and normative consensus.

3. Public spiritedness will continue to be difficult for donors through the coronavirus crisis

Principled nationalism involves a commitment to unselfish, public-spirited behaviours. It requires donors to concentrate on maximising development impact in the long-run rather than searching for narrow domestic returns in the short-run. Almost all donors declined on this component on the Index with Sweden, Spain and Greece performing particularly badly.

Overall, well-ranked countries declined more than the worst scorers. This suggests universally negative pressure on the integrity of aid spending that is likely to jeopardise the speed and efficiency with which aid achieves its aims. The inward-looking donor responses in the early months of the coronavirus crisis align with this trend, including:

- the rush to secure advance vaccines purchases;

- the asymmetry of domestic and global fiscal supports;

- and export bans on medical equipment, diagnostics and drugs.

Against the backdrop of global scarcity, domestic hardship and elevated death rates, wealthy donors look set to continue privileging national commitments and constituencies over international ones.

On the cusp of a Joe Biden presidency, a breakthrough coronavirus vaccine and a G20 led by Italy, the time for changing course is now. Humanity's shared vulnerability to a virus is a real opportunity for the complementary pursuit of sovereign goals and solidaristic values. Principled nationalism may yet pave the long road to recovery with more than good intentions.