After a week of speculation, the chancellor’s announcement to cut the official development assistance (ODA) budget at yesterday’s UK spending review came as no surprise. The ODA budget had already taken a major hit this year as a result of forecasted falls in gross national income (GNI). Yesterday’s move to reduce targeted ODA from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI will see the overall ODA budget shrink from £15 billion before the pandemic to most likely just over £10 billion in 2020/21.

The costliest time to cut

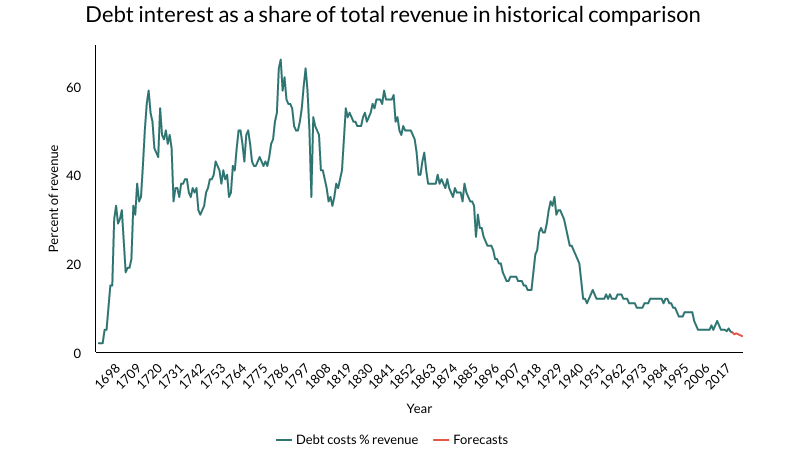

The announced cuts have been framed as a required ‘emergency’ measure that responds to the shock to the UK’s public finances caused by the pandemic. Although there will be a need to rebalance the public finances at some point in the future, there is not an urgent and immediate need to cut spending. While the stock of public debt has risen significantly in the wake of the crisis, the costs of servicing debt remain at historic lows (see chart below). The savings from the aid cut are also a drop in the ocean relative to the size of this year’s deficit (£394 billion).

Original graph presented in Outlook for the public finances (IFS, October 2020).

Data source: ‘A millennium of macroeconomic data’ (Bank of England); Public Finances Databank, Office for Budget Responsibility (July 2020).

Of course, the real fiscal ‘emergencies’ lie in many of the countries who have historically benefitted from UK development assistance. Here the timing of these cuts could not be worse. Without a greater international financing response, current International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts show that governments in the least developed countries will have to cut back spending just as the pandemic begins to subside.

A lack of international finance to support recovery today increases the likelihood of more costly debt relief needed in years to come (the UK continues to spend in the region of £200 million per year to support the previous multilateral debt relief initiative). Proposed cuts to aid could also hamper efforts to provide equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines, as to its credit, the UK has also historically been the second largest global health donor.

A changed vision of the UK state and its place in the world?

It has been said that “the budget is the skeleton of the state stripped of all misleading ideologies” (Rudolf Goldscheid). What then does the spending review tell us about the UK’s vision for its place in the world?

The proposed cuts to ODA seemingly constitute a dramatic reversal of the spending policies of the Conservative-led coalition government following the global financial crisis. At that time the government maintained and, for the first time realised, Labour’s commitment to spend 0.7% GNI on ODA – even as they embarked upon a series of swingeing spending cuts in other areas as part of efforts to reduce the overall size of government spending.

While last year’s Conservative manifesto reiterated the 0.7% commitment, the chancellor is seeking to project very different mood music to his predecessors. On the ‘Global Britain’ front, the savings from the ODA budget could be argued to have been redeployed to a ‘once in a generation’ modernisation of the UK’s defence capabilities. In 2022/23, capital spending in the ministry of Defence will be £5.5 billion greater than in 2020/21.

As support for ODA was cut, the chancellor was also keen to emphasise a more compassionate domestic agenda. The chancellor committed to increasing spending on public services, but proposed total expenditure levels of 42% of GDP by 2025-26 do not suggest a radical departure in how public services are funded. A fund aimed at addressing regional inequalities in infrastructure sounds somewhat similar to previous European investments in deprived regions. Efforts to ‘level up’ do not seem to extend to maintaining a £20 weekly increase in universal credit, despite the acknowledgment of lasting economic scars caused by Covid-19

The £12 billion made available for the UK’s green industrial revolution was a welcome boost to efforts to address climate change. However the sums involved pale in comparison to the overall investments that have been made to respond to the Covid-19 crisis (coincidentally it is the same amount as was spent on the outsourced test and trace systems). No potential savings were identified in the UK’s £12.8 billion worth of subsidies to fossil fuels.

What next?

Whether the proposed cuts to aid spending are temporary or permanent remains an open question. If there were sufficient parliamentary or public opposition, there could of course be a U-turn. Over the past week, there has been vocal opposition to aid cuts from many long-term supporters of international aid, including five former Prime Ministers (subscription required).

Yet the reality is that this year’s aid cuts do not seem (to date at least) to have caught the public imagination in the same way as, for instance, Marcus Rashford’s campaign to protect free school meals. It was notable that the foreign secretary’s defence of aid was written in the Financial Times (subscription required).

The government will also be keen to quickly shift the terms of debate on to announced measures on how a reduced aid budget will be used more effectively. In that respect, there is much to recommend in the letter that Dominic Raab sent to the Chair of the International Development Commission (and this article that seemed to help inform it).

While the timing of the cuts is horrendous, they provide an opportune moment to reinvigorate public debate about the UK’s wider role in supporting (or impeding) development in the coming years. At times in recent years, it has seemed like UK development policy has been more about hitting a numerical target than seeking to foster a more consensual vision of the UK’s place in the world.

Antoine Lacroix provided research support for this blog.