The International Development Association (IDA) – the concessional lending arm of the World Bank – is one of the main sources of external funding to governments where the world’s poorest and most vulnerable populations are concentrated. Such countries typically cannot borrow at scale – or at all –from international capital markets.

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, IDA has been providing much needed countercyclical funding at concessional terms, especially when bilateral aid stayed almost flat. Although IDA has received some criticism about not doing enough, it scaled up its operations by nearly 50% in 2020 compared to 2019.

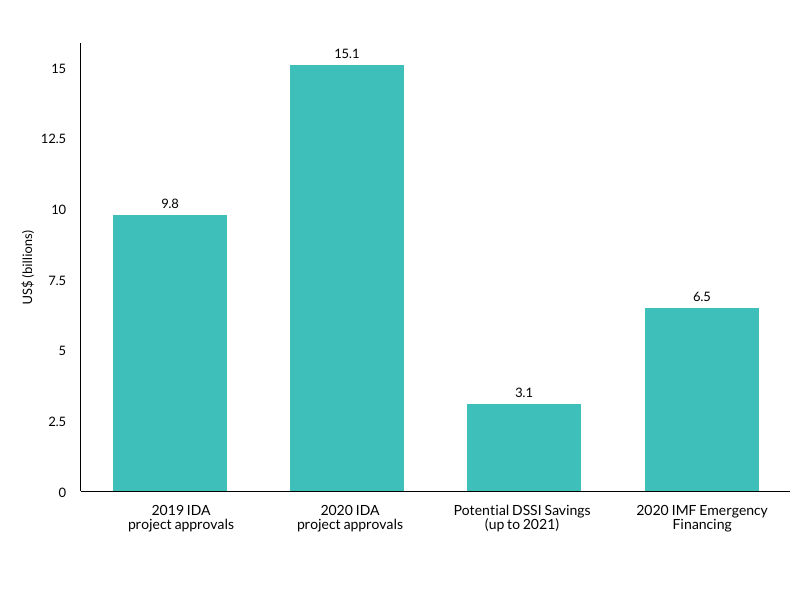

There is also space for further expansion in 2021 thanks to a combination of a record-high replenishment round for the 19th IDA cycle (IDA19) and resources being frontloaded. In particular, IDA project approvals in 2020 grew more than the total savings projected for the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in IDA countries that have so far applied for it (see figure 1). Repayment terms for IDA credits are also more generous, e.g. with longer maturities, than the International Monetary Fund (IMF) emergency financing facilities.

Figure 1: IDA project approvals, DSSI savings and IMF emergency lending (for IDA-only countries that are DSSI participants), US billions

Source: Elaboration based on World Bank project approvals (as of 31 December 2020), DSSI webpage (downloaded 8 January 2021) and IMF Covid-19 Financial Assistance and Debt Service Relief (downloaded 8 January 2021).

This expansion of IDA grants and credits in 2020 and 2021 comes at a price though. Unless shareholders pledge additional contributions in 2021 – the current IDA19 cycle is due to end in June 2023 – or if lending policies change, IDA operations are expected to fall by 35% in 2022. This would mean a drop from $35 billion in 2021 to $22.5 billion in 2022. If more countries are assessed to be at greater risk of debt distress as a result of the crisis, then the sum of IDA funding will fall even further. This is because a greater proportion of the overall IDA envelope will be paid out as grants.

This note explores:

- the implications of a potential sharp fall in IDA resources in 2022 and what this could mean for the prospects of economic recovery in lower-income countries

- how the financing, allocation and use of future IDA resources could best support recovery in lower-income countries.

Prospects for economic recovery in IDA countries

It is already apparent that the Covid-19 crisis will create lasting social and economic scars, although these will be felt unevenly both across and within countries. The World Bank estimates that as many as 150 million people might fall into extreme poverty by 2021, reversing progress made over the past three years. And this is not temporary.

The World Bank also assesses that 250 million more people will be in extreme poverty by 2030 compared to last year’s projections. Evidence from previous crises (e.g. droughts) shows that this can have lasting effects on socioeconomic development. Sustained disruption to education will affect human capital formation and, in turn, long-term growth.

As the Covid-19 crisis gets longer, the likelihood of these lasting impacts will grow. Without a comprehensive package of policy reforms, “the global economy is heading for a decade of disappointing growth outcomes,” as the recently released World Bank Global Economic Prospects bluntly put it.

Effective containment of the pandemic will be the most critical aspect of recovery. As the vaccine roll-out accelerates in advanced economies and in certain middle-income countries, there is increased confidence that a significant proportion of their population will have been vaccinated. There is also hope that the most onerous virus containment measures at the national level will be lifted towards the end of 2021.

By contrast, vaccine coverage across countries and regions elegible for IDA funding is likely to be limited. With a worrying slow start in 2021, widespread access to vaccines is not expected until 2022 or even 2023. This means that certain sectors, such as services and tourism, will continue to be affected by travel restrictions for another two to three years. Economies that are heavily reliant on these industries were the worst affected in the early stages of the Covid-19 crisis.

Fiscal policies can help minimise some of the lasting impacts of the Covid-19 crisis. In the initial phase of the pandemic, policy-makers were urged to do ‘whatever it takes’ to minimise the effects on health systems, households and firms. The IMF and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are urging governments in advanced economies to maintain expansionary fiscal polices to support economic recovery once the pandemic has been brought under control.

Lower-income countries have been much more constrained in their ability to shield firms and households from the effects of the crisis. These governments were already more indebted before the Covid-19 crisis struck than in the late 2000s, and even more so towards the private sector. The economic shock has also caused tax revenues and foreign exchange inflows to fall, and limited new grant financing has been made available to support the crisis response. As a result, most IDA-eligible countries have taken on emergency IMF financing to help weather the initial phase of the pandemic.

Looking ahead, a rapid decline in international financing increases the risk that governments in IDA countries will cut back on spending or raise taxes even before the virus is fully brought under control. The IMF estimates that $290 billion of the external financing needs of sub-Saharan African countries – many of them IDA countries – for 2020-2023 are yet to be met.

How IDA should support recovery from the Covid-19 crisis in lower-income countries

IDA’s core ambitions are to boost economic growth, reduce inequality and improve livelihoods in the poorest and most vulnerable countries. But as a result of the Covid-19 crisis, achieving these aims has become significantly more difficult. There are also short-term challenges to contend with. These include greater risks of macroeconomic instability and quickly recovering some of the economic activity that has been lost. How can IDA balance these short-term challenges and long-term development needs?

IDA funding should prioritise government spending policies that support IDA’s long-term core objectives. In addition, projects that get cash to businesses and citizens will raise demand in the economy and help to maximise the short-term fiscal multiplier (this means, the ratio of change in output to a change in fiscal policy over the first one or two years). Such policies should be timely, targeted and temporary.

In the current context, timely would mean interventions should be adapted depending on the progress of vaccination programmes and the reopening of economies. Instruments and programmes that are quick to implement and get money flowing to service provision, businesses and households should be chosen. Targeted policies would require a larger crisis response window to be allocated to countries and sectors most adversely affected by Covid-19, to achieve high multipliers in the short run through greater use of local content. The additional intervention should also be temporary, without loading spending pressures onto the national budget once IDA funds are withdrawn.

Increasing the scale of resources

Most immediately, the longer than expected downturn of the economy and the front-loading of IDA19 grants and loans in 2020 and 2021 call for an increased funding envelope. This is to ensure that IDA operations do not fall in 2022 and 2023 when they will be most needed. There are three potential options to increase the scale of resources available to IDA to support the Covid-19 recovery.

1. Increase IDA’s own resources

New donor pledges in 2021 of sufficient scale, or an early replenishment, could enable IDA grants and loans to maintain current levels of financing in to 2022.

2. IDA could issue additional bonds in international capital markets to leverage its balance sheet

As of 2018, IDA had $163 billion worth of paid-in shareholder capital. Given the severity of the crisis, there is an argument to be made on drawing upon the capital to expand financing (PDF). However, this would reduce IDA’s financing capacity over the longer-term.

3. Change the financing terms to allow for higher volumes of concessional loans, relative to grants

This could be done by allowing countries at high risk of debt distress to receive a small proportion of funds through concessional loans (i.e. a 80% grant, 20% loan mix). The mix between grants and loans for countries assessed at being at ‘moderate risk’ of debt distress should change, for instance to 40% grants and 60% loans.

Given the scale of the crisis, we believe there is a strong case for pursuing all three options. Relaxing financing terms clearly entails risks around debt sustainability. Future debt dynamics will depend on how any additional funding would be invested (discussed in more detail below) and factors outside the control of national policy-makers (most notably, global efforts to contain the pandemic). However, on balance, the risks of doing ‘too little, too late’ to protect economies and support recovery appear greater.

Allocation across countries

The performance-based allocation of IDA resources is determined by the country’s gross national income (GNI) per capita – a proxy for poverty – and a weighted average of the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) – a proxy for the country’s ability to use resources effectively.

The core IDA allocation should be weighted more towards GNI per capita and less towards the CPIA. It has been estimated that by 2030 the number of countries with extreme poverty rates above 20% of their population will increase by 50%. Nearly all low-income countries are now expected to have higher rates of extreme poverty (83% of all low-income countries compared to 58% before the Covid-19 crisis). Public spending in countries understood to have weaker institutions does not necessarily have a lower impact on growth (PDF) than in countries where spending is considered to be more ‘efficient’.

That said, there would be merit in a window that allocates additional IDA resources to countries where IDA funds can have the greatest impact in supporting a quick economic recovery. One of the criticisms of the World Bank response to the 2008-2009 financial crisis was that new lending reflected pre-crisis lending patterns, and that its correlation with the severity of the crisis impact was low. The IDA performance-based allocation reflects GNI per capita and the strength of institutions and policies, but not how a particular economy has been impacted by a particular shock.

The creation of a dedicated economic recovery window that builds in greater flexibility beyond the IDA country allocation would help to address this shortcoming. It would also likely need to be larger than the existing Crisis Response Window (up to $2.5 billion in IDA19). Consideration should be given to how the shock from the Covid-19 pandemic has affected the economies of IDA countries and what that means for the longer-term prospects of economic transformation. In countries that have faced a slump in demand in labour-intensive sectors resulting from the pandemic (e.g. tourism, garment industry), there is a strong case for providing large-scale additional financing to help such industries to quickly recover, and to re-employ local labour. The IDA19 Scale-Up Window (PDF) is demand-driven and embeds some flexibility beyond the IDA country allocation as well. However, it offers non-concessional loans only at IBRD terms to countries at low or medium risk of debt distress

Use of IDA resources within countries

IDA funding should prioritise government spending policies that minimise risks of permanent scarring from the crisis, but also support increased demand in the economy over the short-term. This means designing programmes that help stimulate local economic activity. IDA investment projects focus on delivering development outcomes at the lowest cost, usually through international competitive bidding. But this can lead to missed opportunities to channel aid through local actors and make greater use of local content – goods produced in the country and services provided by domestic firms – to maximise the short-term fiscal multiplier.

For example, when IDA funds road construction through international competitive bidding it is likely a foreign firm will be used due to difficulties encountered by local suppliers accessing procurement markets (PDF). While the recipient country benefits from the new road, the foreign firm will likely use more imported goods and foreign labour. Many other forms of development finance use tax exemptions for foreign aid that further disadvantage local firms and mean no taxes are paid to the host country.

A reform of IDA mechanisms to support the greater use of local content is unlikely any time soon. However, there are already some instruments that channel IDA funding through government or local partners where the local economic impact of aid is higher (and so is the short-term fiscal multiplier). For example:

1. Expand the share of IDA assistance disbursed as development policy loans (DPLs)

Using DPLs (or instruments akin to budget support) means funding is channelled directly through governments. Financing through national budgets is estimated to have a greater local economic impact, and would therefore likely have higher short-term fiscal multipliers. DPLs also usually come with conditions on policy reforms (and note that DPLs can only be deployed if the macroeconomic framework is deemed to be “adequate”). At the time of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, the share of DPLs surprisingly declined. But data for 2020 shows a rise in the use of DPL compared to 2019 (23.8% of IDA project approvals were DPLs in 2020; 21.8% in 2019, elaboration based on the latest version of the ‘World Bank Projects & Operations’). This trend should continue and expand in 2021 and 2022.

2. Increase the share of Programme for Results (PforR) programmes relative to traditional investment lending

By using a country’s own institutions and processes, the PforR modality would help make greater use of local labour, goods and services in IDA projects. It could also increase the short-term fiscal multiplier.

Programmes in priority sectors could also be designed in a such a way to help maximise short-term multipliers. Examples that could fit this approach include:

3. Fund social protection programmes

The provision of social transfers can have high short-term multipliers. This is especially the case when targeted at lower-income households with a higher marginal propensity to consume than higher-income households that are more likely to increase savings. Expanding these programmes can also contribute to poverty alleviation in the longer-term. This may be in the form of cash assistance, or by building upon well established food relief infrastructure in certain countries. Where it is difficult to expand programs quickly through government systems, for example due to limited information on household income or payment mechanisms, local government and non-state institutions (such as local NGOs) could be used to identify and assist vulnerable groups.

4. Public work programmes to support infrastructure maintenance

Smaller-scale public work programmes at the local level can have larger short-term fiscal multipliers than large-scale infrastructure projects. This is because they are usually less complex, and therefore can be implemented relatively quickly using local labour, goods and services. Large-scale infrastructure projects have longer lead-in times and tend to require more foreign firms and labour, so the benefits can either be felt too late or leak overseas.

5. Investment in non-wage spending in social sectors

This would stimulate business activity – when provided by local markets – with potential knock-on effects for productivity. This could include increasing capitation grants used to buy books and classroom equipment, or temporary grants for schools to offer more learning support due to school closures and lockdowns. It could also cover increases in funding for hospitals and health centres to purchase medical equipment.

6. Design projects that support central banks to provide lines of credit or guarantees to firms who have taken on loans to weather the crisis

Many governments around the world have instructed the banking sector to offer generous lending terms to firms to help weather the crisis. However, as the duration and impact of the crisis continues, the likelihood of loans being quickly repaid has receded. Writing off loans to firms in certain targeted sectors could be a useful way to support economic recovery.

7. Support Covid-19 vaccine procurement

Certain governments may choose to invest in mass vaccination programmes that build coverage over and above the 20% assured by the COVAX initative. The immediate health benefits of vaccinating a greater proportion of the population might not be as great as some alternative investments (e.g. in malaria prevention). However, widespread vaccination is likely to have implications for access to global markets that are particularly relevant to certain economies (e.g. those that rely on tourism).

Across all investments, efforts are needed to cut the length of the project preparation cycle. DPLs could help fast track disbursements of IDA funds, but this should be part of a general effort towards streamlining the project cycle. The latest figure available indicates that the time for “operational delivery” for World Bank projects was 25.4 months in FY 2017 (fiscal year). This is about two years.

The way forward

IDA grants and credits constitute a major source of financing to the world’s poorest countries. By frontloading resources in 2020 and 2021, IDA financing will reduce significantly in 2022 unless measures are taken. Falling IDA grants and credits will contribute to the risk of governments in lower-income countries cutting spending or raising taxes, even before the pandemic is fully brought under control.

For this reason, contributing IDA members should step up their efforts (consistent with their own fiscal stimulus programmes). They should do this either by topping up the resources for IDA19 or by bringing the pledging session of IDA20 forward to December 2021 for greater commitments to materialise in 2022.

In return, IDA also needs to be much bolder in its proposed measures to respond to the crisis given its severity. This means taking measures to push the financing envelope now, even if that means reduced financing capacity in the longer-term. It also means being bolder in how IDA provides funds. Here the onus should be on investing in programmes and projects that support longer-term development ambitions, but also get money in to the local economy. The risk of doing too little, too late is much greater.

We thank Jessica Pudussery for excellent research assistance as well as Chris Humphrey and Alastair McKechnie for comments on an earlier draft.

This article was amended to clarify that IDA funds can be used to pay local taxes, while many other forms of development finance are tax exempt.