At the United Nations last week, the Secretary-General convened governments and civil society organisations to identify how to achieve Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) by 2030. SE4ALL head Kandeh Yumkella rallied participants around the slogan ‘turning commitments into kilowatt hours for real people.’

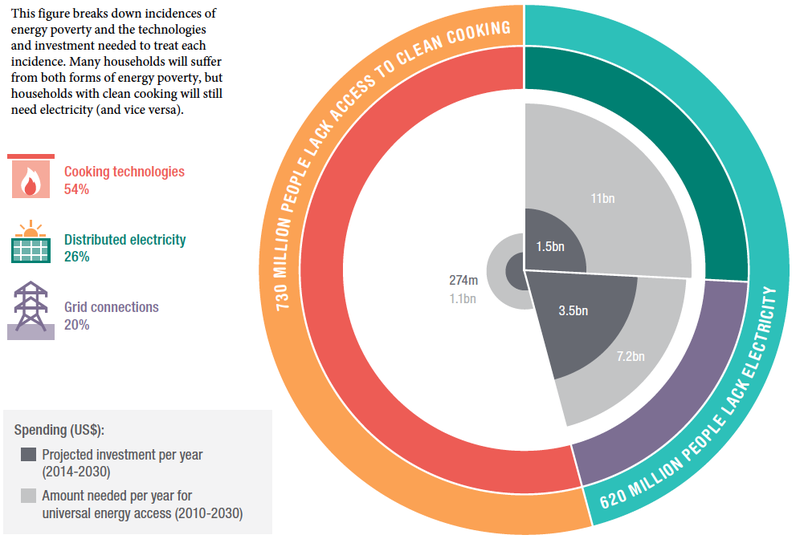

The slogan was as stirring as the need is great. Energy poverty – lack of household access to a base level of electricity and quality of cooking – remains remarkably widespread. In sub-Saharan Africa alone 620 million people, or over two-thirds of the population, lack access to electricity; 730 million people, or 80% of the population, lack access to modern cooking services.

Yumkella’s rallying cry galvanised participants, but speakers and online commentators transformed it in a revealing way. In a matter of hours, they had shortened it to: ‘Let’s turn commitments into kilowatt hours.’

This illustrates a deeper tension in the universal energy access agenda. The idea that dramatic scale-up of power generation is the main ingredient for universal energy access is deeply ingrained. A new report launched by ODI and Oxfam, on the other hand, shows that the biggest challenge to eliminating energy poverty is not turning commitments into kilowatts, but getting them ‘to real people.’

Energy distribution – not generation – is the main problem

It is true that Africa has far less power generation than any other continent. However, even ambitious scenarios for expanding Africa’s power supply leave 530 million people without electricity in 2040, and 653 million without modern cooking services.

This is because Africa’s current power system does not deliver energy to poor people.

About half of current electricity consumption in Africa is used for industrial activities – mostly mining and refining. While industrial growth can and must reduce poverty, in sub-Saharan Africa extractives-led industrial growth has a poor track record of doing so.

Even in parts of Africa ‘electrified’ by the grid, poor households can’t afford connection charges and remain without electricity for years, even decades.

Most important of all, though, is that the conventional model of centralised generation, transmission and electrification is not cost-effective for many households on a continent as sparsely populated as Africa – especially with the plummeting prices of off-grid renewable technologies.

Off-grid energy sources

As the illustration below shows, most cases of energy poverty in sub-Saharan Africa are treated most cost-effectively by distributed, off-grid sources. Liquefied petroleum gas, biogas digesters and advanced biomass cook stoves are the cheapest options for cooking. Solar, mini-hydro, and diesel and hybrid-solar generators are the cheapest ways to supply most unelectrified homes. Off-grid sources are also generally the most cost-effective option to supply schools, primary health clinics (pdf), and small businesses in rural areas. By contrast, on-grid sources only serve 20% of energy poverty needs.

Source: Data from IEA, 2014 and IEA, 2011

Source: Data from IEA, 2014 and IEA, 2011

These energy poverty needs are in direct contrast to energy spending. A recent report by Oil Change International shows that the World Bank invests only 13% of its energy financing in energy access. Second, the money that is spent on energy access favours grid connections. But as this illustration shows, securing electricity access through distributed systems requires over 2.5 times more investment than securing electricity access through grid connections.

Ending energy poverty: the biggest challenge is reaching real people

The main challenge to ending energy poverty is not the technical one of radically expanding power generation; it is orienting policy to deliver energy to those who need it most. In our ambition to rapidly expand electricity generation, the formidable task of achieving universal energy access could be lost.

The significance of Yumkella’s rallying cry is clear. Energy commitments cannot just turn into numbers of kilowatts and megawatts, but must turn into the number of real people who benefit from the vision of energy access for all.