Over 700,000 people have reached the EU's borders since early 2015. At least 3,103 more have died trying to get there. Europe is facing the biggest migration crisis since World War II.

There are actually two crises unfolding in parallel. The first is a global displacement crisis, with ever more people fleeing conflict, violence and violations of basic human rights from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Eritrea and elsewhere.

The second is a crisis of EU migration management. The events of this summer have been the ultimate test. Standard policy responses have been found wanting. One thing is clear: the current system is not fit for purpose.

High-level EU officials are meeting next month in Valetta to discuss a way forward. Ahead of those negotiations, here are three things you need to know about current European migration policy:

European migration policy is utterly incoherent

We talk of European migration policy, but the migration regime is defined far more by the actions of individual states. European countries have long made bilateral agreements with ‘source’ countries in a bid to regulate immigration. In 2006 for example, Spain drew up an agreement with Senegalese authorities to fund temporary jobs in Senegal in exchange for tighter monitoring of Senegalese borders.

The kinds of decisions we saw in recent months – the Hungarian border fence, Germany's tearing up of the Dublin Agreement – are simply a continuation of unilateral policy making by European countries acting independently.

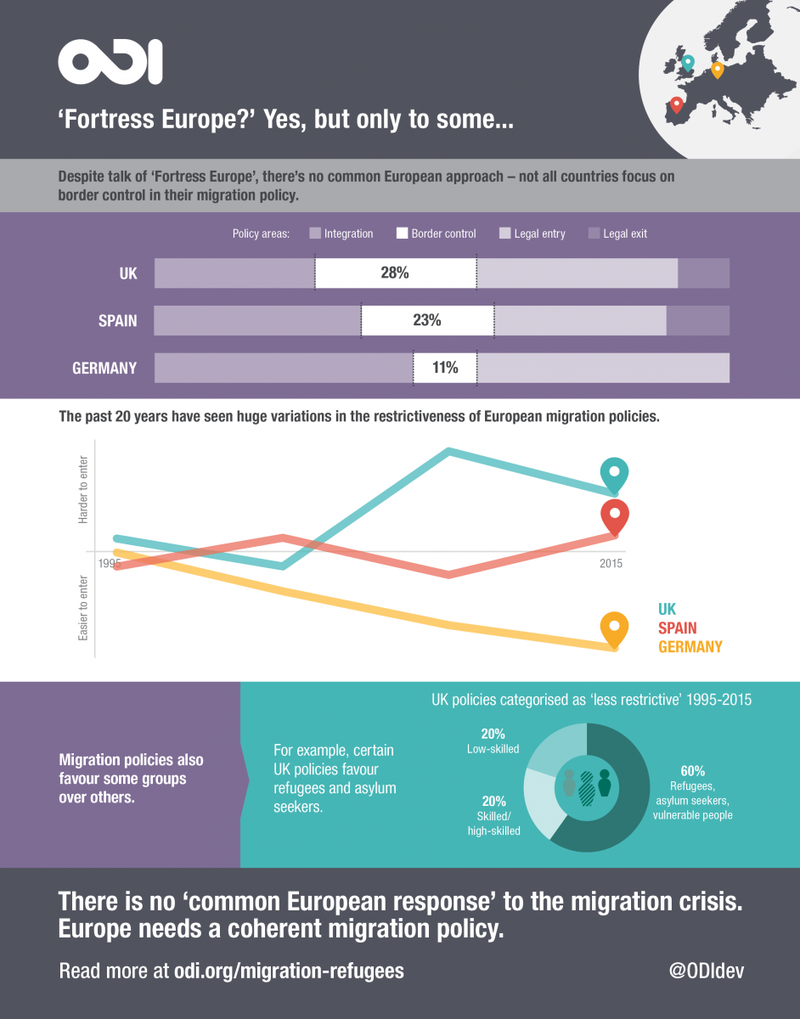

In a recent policy mapping exercise, we looked at the kinds of migration policies implemented in Germany, Spain and the UK over the past 20 years. We saw some big differences. Certain countries seem to favour certain policy areas. Contrary to what you might think, it’s not always border control.

For example, almost half of Germany’s migration policies over the last two decades focused on the integration of migrants and refugees. At the same time, and over the same period, more than a quarter of the UK’s policies targeted border control – a higher share than both Germany and Spain.

The purpose of migration policies is either to make it easier or harder for people to enter and remain in a country. We asked: over the past 20 years, which of these two opposing motives dominated the migration regimes of Germany, Spain and the UK?

To work this out, we drew on the analysis and methods used by DEMIG – the excellent Determinants of International Migration project at Oxford University. Following their approach, we found that while all three countries implement both types, the UK’s policies have generally become more restrictive over time while Germany’s have become less restrictive. Spain is a little all-over-the-place, going back and forth over the years.

European migration policy reinforces global inequality

Migration policies are rarely blanket approaches. They tend to target specific groups of people.

So while a country might become more open to certain categories of migrant, it can also become more closed to others. In the early 2000s, for example, Germany introduced a series of policies designed to attract skilled migrants, while making migration for family reunification purposes more difficult.

And despite the clichéd rhetoric, governments’ pro-immigration legislation doesn’t always focus on highly skilled migrants: most of the UK’s less restrictive policies over the last 20 years have actually been targeted towards refugees and asylum seekers, making it (relatively) easier for them to enter.

So, Europe is a fortress for some, but not for others. Some can enter with relative ease; others are confronted with fences and teargas.

Why does this matter?

To address global poverty, EU countries sent a total of €56.1 billion in aid in 2014. At the same time, evidence suggests that the movement of people from the poorest countries into Europe has become increasingly restricted. The most absurd thing about this is the fact that international migration is the most effective method of poverty reduction we know of – far more transformational for the migrants and their family than aid could ever hope to be.

European migration policy doesn’t stop people migrating: it just makes it harder

So, are migration policies effective in reducing ‘undesirable’ migration flows? More research from DEMIG shows that the only impact more restrictive visa and asylum policies achieve is push potential and rejected applicants into irregularity. It is also obvious that migration policies are probably far from people’s minds when they flee violence, conflict or poverty. Motivations for going to a particular country are diverse, ranging from access to employment opportunities to the language spoken.

When legal migration corridors are tightened and countries' borders become more closed, people don’t stop coming: they just change their route. As part of that process, smugglers become more in-demand and journeys more dangerous. Over 22,000 migrants have died trying to reach Europe since 2000, with the use of risky migration routes – crossing the Mediterranean on flimsy dinghies, struggling through the Libyan desert on an overloaded truck – being a direct response to current migration policy. Driven, determined people continue to make the journey, regardless of how lethal it might be.

For this reason, harsh border controls will never be an appropriate management response to one of humanity's most basic compulsions: to move in search of a better life.

The policy mapping is the first output of the ODI project ‘The governance of mobility: a people-centred analysis of what the Fortress Europe border regime means for the migration-development nexus’. This project looks at when and how migration policies affects people’s decisions, based on interviews with Eritrean, Senegalese and Syrian migrants in Berlin, Madrid and London.

For more information contact: Jessica Hagen-Zanker and Rich Mallett