In 1995, more than 40,000 women’s rights activists and leaders convened at the Beijing Fourth World Conference on Women. Together, they set a goal to achieve the ‘full participation on the basis of equality in all spheres of society, including participation in the decision-making process and access to power.’

Many gains

As we now approach the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Conference, we’ve seen some dramatic achievements.

For one, the 1990s saw an explosion of female firsts and a steady uptick in women’s representation. During the 1980s, only six women served as their nation’s first head of state. By the 1990s, this number jumped to 16.

In 1995, seven UN member states still denied women equal voting rights to men. Now, gendered voting has ended in all territories except the Vatican, after Saudi Arabia finally enfranchised women and provided for them to run for municipal office in 2015. Twenty years ago, there were no female CEOs of Fortune 500 countries, now there are 25.

But many miles to go

These changes, though exponential, are still very fresh. Just two years ago, when 15 female world leaders held office, eight of them were their country’s first woman in power.

So, what can be made of the progress and challenges in the 25 years since Beijing? Here are five points to consider in the post-Beijing agenda:

1. While progress has been fast paced, it has been uneven and may plateau

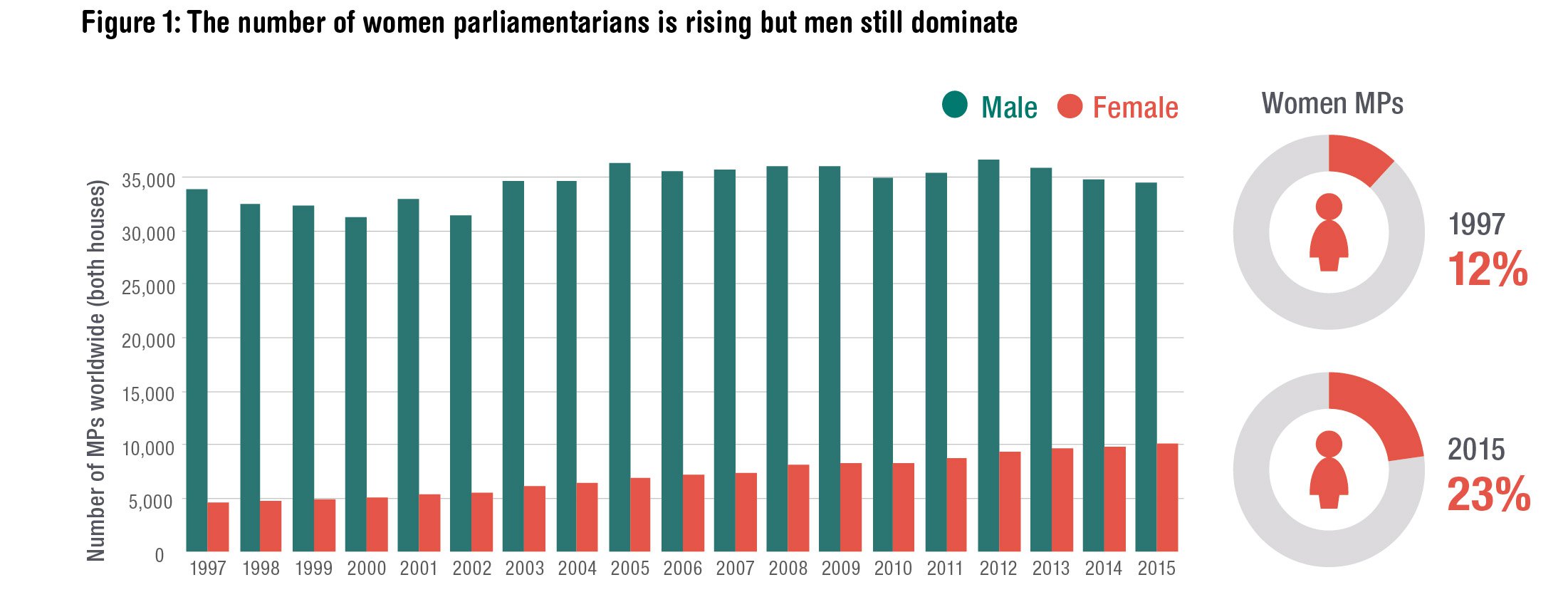

The number of national female parliamentarians globally grew from 11.3% in 1995 to 23% in 2015. Today, it is 24.3%. While this figure has more than doubled since Beijing, it remains low. Based on current trends, women will not have equal representation in parliaments until 2065, and will only comprise half the world’s leaders in 2134.

Progress also varies regionally, with concentration of female heads of state overwhelmingly in Europe (although a greater proportion of women in India are more actively engaged in the political process than in Germany, Denmark or the UK).

2. Quotas and other policy tools are important, but do not always mean real changes or equality for women

As ODI research demonstrates, increasing the number of women in government does not necessarily mean they have any power or influence. Rather, a country’s democratic robustness is key. Women leaders in parliament can sometimes be drawn primarily from elite circles, seen as ‘tokenistic.’ Although an increasingly popular practice, the impact of parliamentary gender quotas remains debated and greater research on their impact is needed.

3. Violence and harassment continue to plague women’s paths to power

Violence and harmful norms can block women’s voice and representation and remain a huge barrier, even when formal institutions and laws guarantee equality. For example, just as King Salman of Saudi Arabia granted women the right to drive in 2018, activist Loujain al-Halthloul was tortured for her advocacy – and remains in prison today. And, even when rights are gained they can be revoked, as was the case with women’s right to vote in Afghanistan.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan, tribal norms and intimidation enforce a rule by which women do not tend to vote. In Northern Ghana, traditions demand women sit behind men at community meetings. These are barriers which must be addressed in order to meaningfully move the dial forward on women in politics.

Furthermore, we must continue to listen to women. As recent ODI research with women’s movements in Nepal and Uganda demonstrates, women have had diverse personal experiences of accessing and sitting in positions of power. Their testimonies, as well as those from prominent female leaders – from Merkel to Zewde – should be further acknowledged and explored.

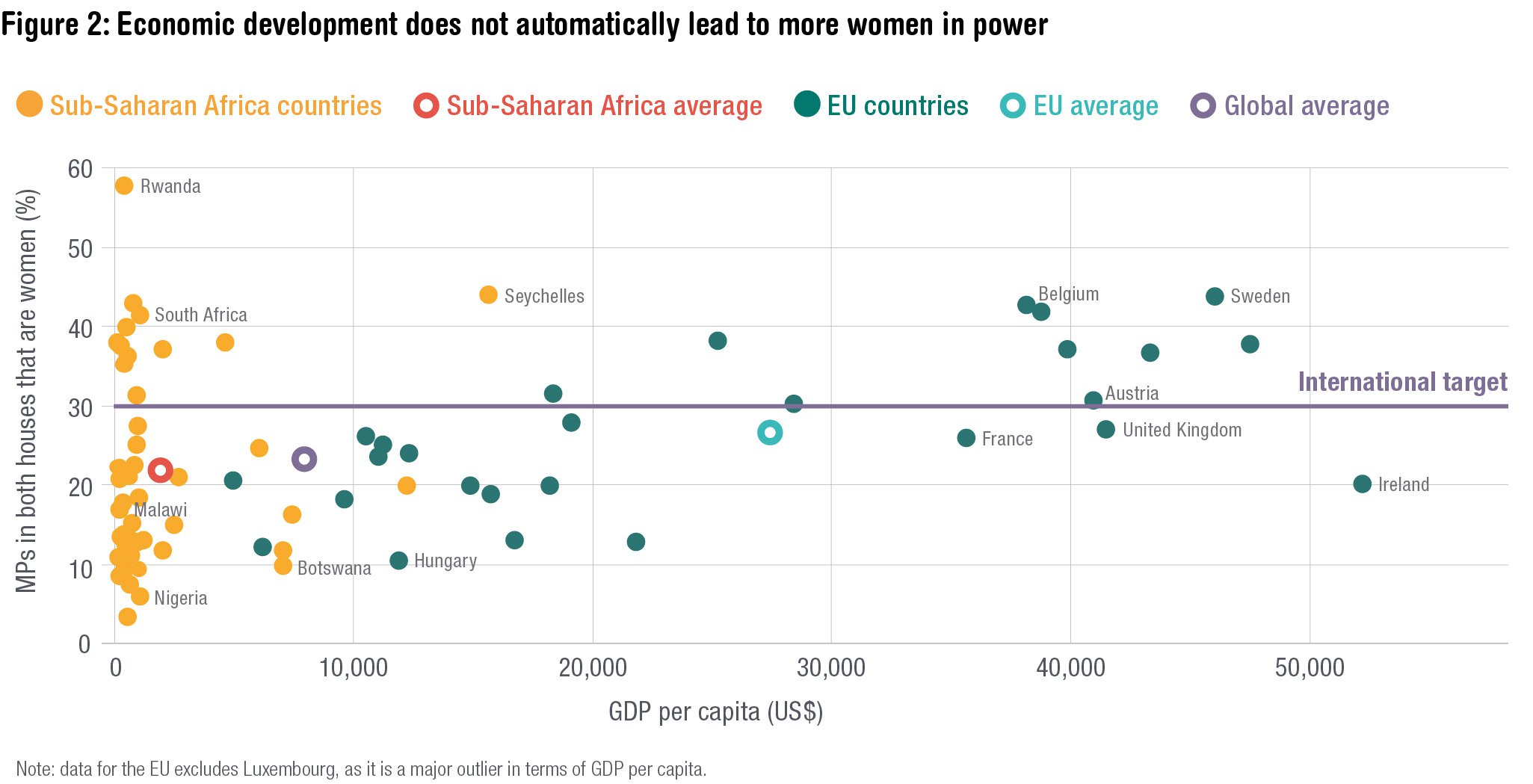

4. Economic growth alone won’t put women into power

While economists agree that gender equality is good for economic growth, increasing the number of women in the labour force does not guarantee more equal roles for women overall. The exploitation and poor conditions for women in the workforce which can come alongside growth should not be overlooked. Women’s political inclusion cannot be assumed to follow economic development.

5. International agendas can be motivating, but they have limits

Global commitments are important. Since 1995, 37 additional states acceded to the 1981 CEDAW Convention. Global conventions and meetings such as the upcoming Commission on the Status of Women can be important anchoring points for advocacy, but they must be backed by action to have meaning. We need more specific goals around political inclusion in global frameworks and agreements to ensure more concrete action.

What’s next for 2020 and beyond?

Melinda Gates recently announced she is investing $1 billion to ‘promote women’s power and influence’ in the United States. Investments like this are important, and should address violence, gendered norms, unequal care burdens, financial inclusion, and other factors marring gender equality in the political space. International actors must also make more explicit programmes, targets and goals specifically on political inclusion to invest in and track progress.

Just as 1995 was an opportunity to coordinate action, 2020 comes not a moment too soon to celebrate an immense amount of progress while also looking to the future and doubling down on the goals set out in Beijing around equality, representation and power.

This blog is part of our ODI at 60 initiative.