Welcome to ODI's Hot Take on all things climate! For our first newsletter of 2024, we dive into the aviation sector's questionable decarbonisation strategy, how 'country platforms' can help developing countries align development priorities and climate goals, and the complex relationship between climate and education.

Airport emissions are taking off (again)

Last year, the Dutch Government put forward plans to cut flights from Schiphol Airport by around 8% a year in a bid to reduce noise pollution and greenhouse gases. Industry lobbying and pressure from the European Commission ultimately blocked the move. But with demand for flying expected to breach pre-pandemic levels next year, emissions from aviation are on the rise, and the case of Schiphol Airport highlights just how difficult a problem it is for policymakers.

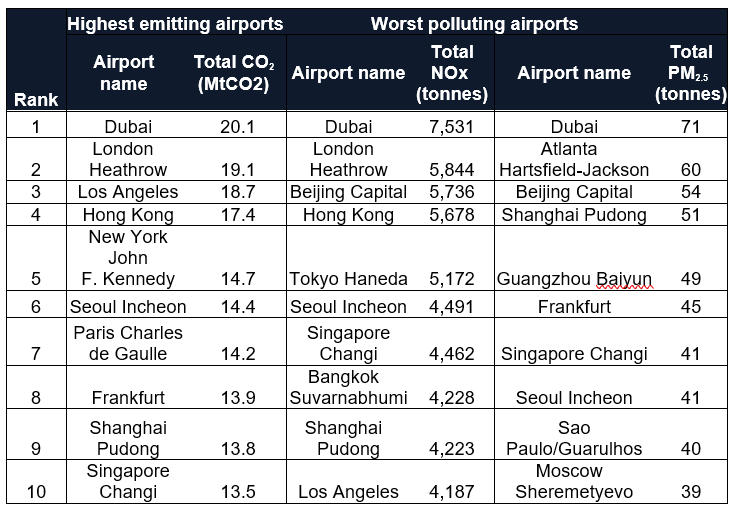

In partnership with Transport & Environment and with data provided by the International Council on Clean Transportation, ODI has just launched the 2024 ‘Airport Tracker’. The Tracker documents the climate and air quality impacts of passenger and freight transport from 1300 airports across the globe.

Dubai International Airport emerges as the most polluting, producing CO2 emissions equivalent to over 5 coal plants. Heathrow was a close second in terms of emissions, but helped London win the unenviable prize of being the city responsible for the most aviation-related air pollution: its 6 airports together produced 8,900 tonnes of nitrous oxide and 83 tonnes of particulate matter (PM2.5).

This new research draws the aviation sector’s questionable decarbonisation strategy into focus, which hedges on a sharp increase in the supply of expensive Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAFs). Yet SAFs currently account for just 0.1% of jet fuel consumption. For the sector to reach net-zero, it would require production to increase a thousandfold from a few hundred million litres a year today to over 400 billion litres by 2050. Airlines also promise that efficiency gains will curb emissions over time, but these are likely to be offset by soaring demand (sorry, pun very much intended).

Emissions generated by airports are therefore set to continue booming, putting millions of people at risk. Globally, air pollution is the 4th largest risk factor for human health, killing 6.7 million people in 2019. And in the medium-term, runaway climate change poses an even greater threat to human life and health.

The Dutch Government’s proposals for Schiphol Airport may not have landed this time (much like these puns), but a net-zero future is only possible with dramatically fewer flights.

'Country Platforms' and the West's half-hearted response to a promising idea

One of the highlights of COP26 was the announcement of South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). The subsequent announcement of JETPs in Indonesia, Viet Nam and Senegal caused nearly as much hype.

These big deals are intended to prove that developed countries will provide substantial finance on generous terms to help developing countries advance both national development priorities and international climate goals.

But new analysis from ODI suggests that the JETPs are not living up to expectations – although these were, perhaps unreasonably high.

- Is there significant new money on the table?

The headline offer from the international partners is equivalent to 1-3% of each country’s annual GDP. But these resources will be disbursed over several years and includes loans reported at face value (in other words, donors expect to recover some of the money that they have pledged). This offer also includes money that was already committed, so the value-add of the JETP is not necessarily lots more money (as the political declarations might imply), but rather better coordination of donors behind each country’s national investment plan. While this promise might not be sexy enough to capture global headlines, developing countries navigating the sea of bilateral donors, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and multilateral climate funds will warmly welcome more joined-up finance. - Will the JETPs ensure that energy transitions are indeed ‘just’?

We find that South Africa has taken the ‘just’ piece of its JETP very seriously, with extensive consultation processes undertaken over many years and ZAR 60.4 billion (USD 4.0 billion) allocated to the most coal-dependent province, Mpumalanga. In contrast, Indonesia’s government was under enormous pressure to announce its new JETP at the G20 Summit in Bali. This limited the time for a proper conversation on what a just transition in Indonesia might look like, which has in turn meant that considering what ‘justice’ really means was relatively neglected in the country’s investment plan. Fortunately, new energy infrastructure takes years to plan and build; Indonesia has ample time to better engage stakeholders and re-purpose funding to the most affected communities, like in Kalimantan and Sumatra. - Can the JETP model be replicated in other countries?

At COP28, the MDBs reaffirmed their commitment to roll out ‘country platforms’ across developing countries. But the politics of climate action are profoundly different from Fiji, to Bangladesh, to Nigeria. ODI has therefore produced a diagnostic to help both domestic reformers and international partners think through how a country platform should be designed. The key conclusion? A JETP-style deal is much more credible when power is relatively concentrated in the top leadership, i.e. groups loyal to the leader are stronger than their rival political factions – as in Senegal or Viet Nam. A JETP-style deal is likely to be much more just when power rests on a broad social foundation, i.e. the leader and his or her (but usually his) followers are incentivised to share benefits such as cash transfers or access to services widely – as in South Africa or Indonesia.

The MDBs will be under the spotlight in two weeks, as the World Bank and IMF host the annual Spring Meetings. Will they be able to fulfil their promise of more and better country platforms? Well, we think they can. To this end, we will be producing insights into how they can best facilitate a smooth energy transition over the coming weeks. Find out more on our dedicated page here.

Climate and education: learning from each other

Throughout 2019, millions of young people participated in school strikes, skipping classes every Friday to lead some of the largest climate protests in history. Their efforts drew attention to the existential threat that climate collapse poses to their futures and the public demand for bolder climate action.

Most have now gone back to school, but – ironically and tragically – climate change is too often interrupting their education. In 2022, Storm Ana destroyed nearly 800 schools in Mozambique, while last year, Cyclone Mocha ravaged 1,337 schools in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. These effects are not confined to the Global South: last year, extreme weather saw dozens of schools across the USA destroyed, like in Indiana, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Georgia, and Arkansas.

Climate change is already having a profound impact on educational opportunities and outcomes across the world through exposure to floods, extreme heat, and natural disasters, but also through impacts on other areas that in turn affect education, such as disease, nutrition and displacement. These are experienced at every level, from early childhood to higher education and beyond and are exacerbated by social factors like income, gender and disability.

But this is not a one-way street. Education is a valuable weapon in our arsenal for tackling and coping with climate change.The more we know, the more we can work together to adapt to our changing climate; the quicker we can learn vital green skills; and the more emission reductions we can unlock across society.

In an effort to enhance our understanding of these complex relationships, ODI has released the Climate-Education Research Framework (CERF): a simple yet structured approach to research at the climate change–education intersection.

CERF links five education levels (Early Childhood, School, Tertiary, Sector Level and Nonformal/Indigenous education) with three climate change thematic areas (Adaptation, Mitigation and Loss and Damage). We hope that this clear structure for understanding the many links and feedback loops between climate and education will enable policymakers from both worlds to start working together.