A series of shocks have hit the world economy: rising prices, the accumulation of public debt, the need to fill critical gaps in services and to address ‘catch-up costs’ following the Covid-19 pandemic.

Finance ministries are under pressure to respond. But how are these forces playing out in practice, and what signals are governments sending in the latest round of budget speeches about the action they intend to take?

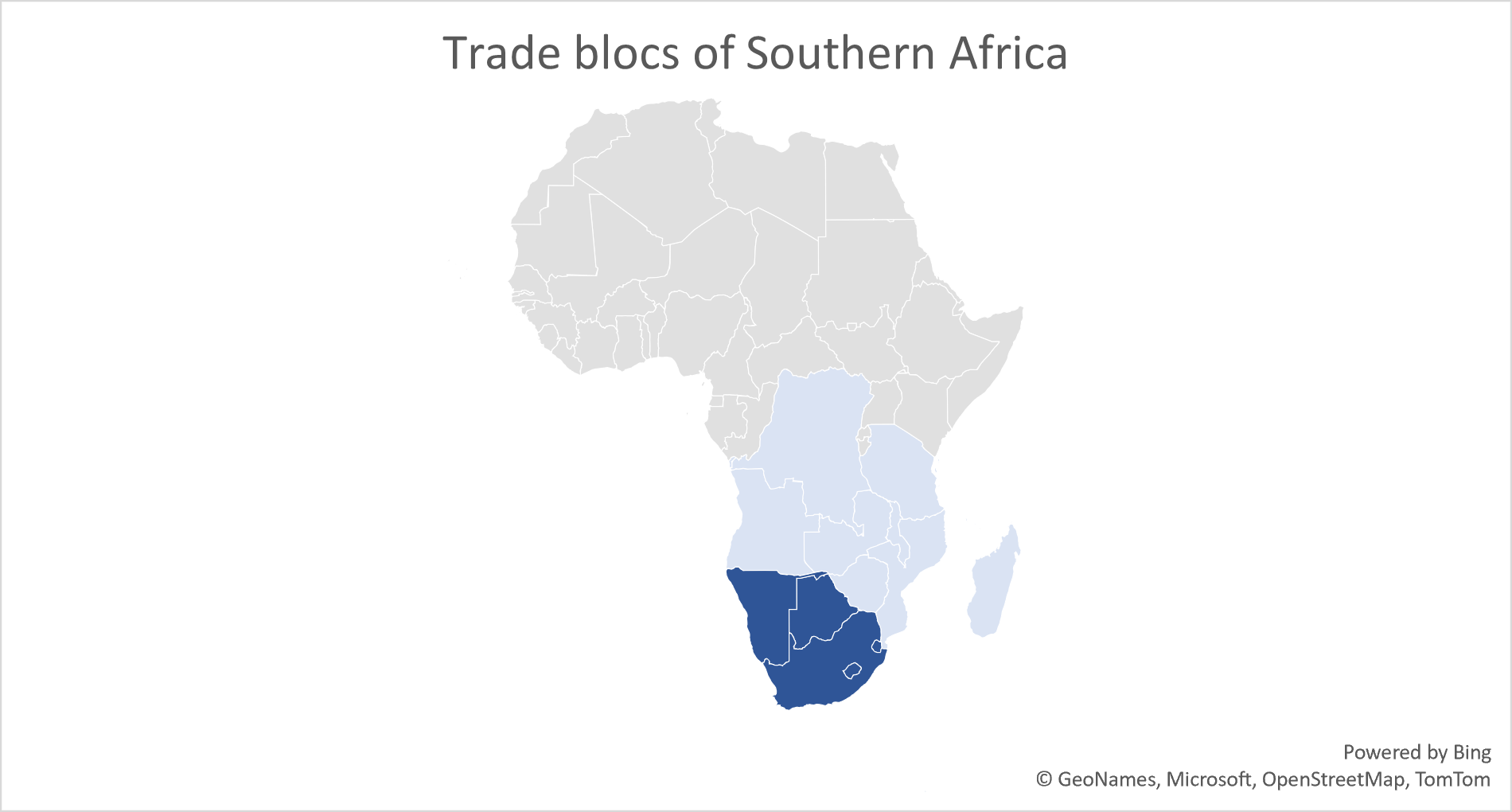

April marked the start of the 2023/24 fiscal year for countries in the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). Starting from early February, South Africa’s National Treasury along with finance ministries from the smaller SACU member states of Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho and Namibia tabled their annual budget speeches setting out tax and spending plans for 2023/24.

A difficult decade

As members of SACU, these five countries have more than just a fiscal timetable in common. Their economies are closely integrated, their currencies are closely linked, and customs and excise revenues are shared between the members using a revenue-sharing formula.

Relative to other countries in Africa, the SACU countries have high levels of GDP per capita (except Lesotho), high levels of government revenues and public spending, and established social safety nets. However, the region has also been among the worst affected by HIV/AIDS, and has struggled economically since the 2008 global financial crisis, with slow growth and rising unemployment.

A significant drought (2018–2020) and then the Covid-19 pandemic have added to these challenges. Of the five states, only Lesotho recorded fewer than 100 Covid-19-related deaths per 100,000 residents according to the WHO, and SACU countries were badly affected economically compared to other parts of Africa.

This mix of longer-term trends and recent shocks means that combined GDP shrank in dollar terms between 2010 and 2022. No comparable cluster of countries has a worse record for economic growth per person during this period.

The 2023 Budget Speeches

Slow economic growth has made it difficult for the governments in SACU to keep up with spending demands, and all five countries struggled to maintain fiscal control as a result. The added shock from Covid-19 has stoked rising public debt (and debt service costs) in Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa. Botswana has relied instead on its large reserves, but the government’s net savings position declined from 40% of GDP in 2008 to minus 20% in 2021.

Against this backdrop, the finance ministers of the five SACU countries have delivered the latest round of budget speeches with a reasonably similar fiscal stance: all of the countries except Eswatini are aiming to run a primary budget surplus (the budget balance excluding interest payments).

But they also strike notably different tones. In Eswatini, the budget speech opened almost with a sigh of relief, with the ‘first fruits’ of economic recovery after difficult years, fiscally and politically. The budget speeches in South Africa and Botswana are stern, with a stated determination to wrestle control over public spending. Namibia is somewhere in between, ‘maintaining a careful balancing act in pursuit of a people-centred but sustainable budgetary framework’.

| Country | Minister | Budget speech date |

|---|---|---|

| Botswana | Peggy Serame | 6 February 2023 |

| Eswatini | Neal Rijkenberg | 24 February 2023 |

| Lesotho | Retšelisitsoe Matlanyane | 27 February 2023 |

| Namibia | Iipumbu Shiimi | 22 February 2023 |

| South Africa | Enoch Godongwana | 22 February 2023 |

The quest for growth in South Africa

South Africa accounts for over 90% of economic activity among the five countries. Its economy is therefore critical to the prosperity of the region.

The 2023 budget speech for South Africa highlighted three general strategies for enhancing growth: fiscal stability; energy and transport sector reforms; and enhanced state capacity for service delivery and controlling corruption.

Of these, the budget speech focused mostly on the significant reforms planned for the energy sector, and a large bailout for Eskom (the state-owned utility company) in particular. This move has been widely welcomed, not least because of the pressures created by load shedding on businesses and households.

However, South Africa is struggling with many other impediments to growth, and there are also questions about the way bailout funds have been budgeted for, whether Eskom can address governance failures without spooking debt markets, and whether government debt levels will stabilise over the medium term as announced.

It is also notable that the budget contains no significant revenue measures, so there will need to be effective spending restraints. One consequence of this policy stance will be lower allocations for the provinces, which have the main responsibilities for basic services.

Rebounding customs revenues ease pressures elsewhere

Underpinning the announcements in the four smaller countries is a sharp rise in the value of revenues shared between SACU members, which make up the large majority of revenue increases this year.

In Lesotho, these revenues nearly doubled from L5.4 billion in 2022/23 to L10.1 billion in 2023/24, and account for over 40% of total revenues and grants in the new budget. This windfall has played the main role in changing a projected budget deficit of 7.7% of GDP in 2022/23 into a budget with a projected surplus of 2.5% of GDP for 2023/24. The story in Eswatini is similar, though the government is still planning to run a deficit of 2.2% of GDP.

Botswana and Namibia have considerable natural resource endowments, but higher SACU revenues are also significant. Botswana’s 18% projected revenue growth is mostly explained by a 70% increase in SACU revenues, which will account for nearly a third of total estimated revenues and grants in 2023/24. Despite the austere tone of the budget speech, total government spending is 17% higher than in 2022/23, and includes a 22% wage bill increase. Namibia is projecting a 16% increase in revenues and a 10% rise in public expenditures, compared to the 2022/23 budget.

An enduring question for the smaller SACU member states is how long this level of transfers will be sustained. In a notable break from the past, the budget speeches in Eswatini and Lesotho announced plans to create stabilisation funds to help manage these volatile revenues in future. Namibia has also laid out plans to create a sovereign wealth fund, following oil discoveries. But time will tell whether these funds accrue enough to help tackle the extreme revenue volatility created by SACU’s current revenue-sharing formula.

Social safety nets are expanding in the face of moderate inflation

While rising, inflation in SACU has not been as high as in some other parts of the world. Only in Botswana, where inflation reached 12.4% in December 2022, did the government adopt particularly aggressive fiscal measures to moderate the impact of inflation – including extending the temporary reduction in the rate of Value Added Tax (VAT) from 14% to 12%. The government has also committed to ensuring ‘that the budget allocation for social welfare programmes has been maintained or increased’.

Protecting the value of social assistance from inflation was central to expenditure policies in South Africa (which extended its working-age distress relief grant again). This is significant because, while pre-tax incomes are highly unequal, South Africa’s government also proactively uses fiscal policy to redistribute income to over 25 million people and social assistance responses to Covid-19 were significant.

In Namibia, the main theme of the budget speech was ‘Economic Revival and Caring for the Poor’ and increases in old age, disability and orphans and vulnerable children’s grants were all notable announcements. Like Namibia, Lesotho pledged to both increase coverage and boost the value of grants, including child grants (up 66% to Namibia’s 40%). Eswatini budgeted to extend safety net coverage.

No big announcements on health and education

There were few notable policy announcements for health and education – the largest areas of spending for SACU countries.

Health allocations have increased in real terms since 2019 in all five countries. However, there is little evidence that the Covid-19 pandemic has permanently raised health spending as a share of total government allocations. It’s possible that this is because governments mostly managed the crisis by reprioritising budgets rather than adding to them. It could also be that temporary spending is being withdrawn. In South Africa, the health budget is lower in the 2023/24 budget than the 2022/23 budget, which may reflect a normalisation as the effects of the pandemic eased.

The longer-term challenge for health spending in the region will be to ensure that it is oriented towards primary care to tackle the majority of the disease burden. But this has often been a casualty of expenditure shocks and is also complicated by an infamous public–private partnership hospital in Lesotho and by national health insurance in South Africa which might struggle to target the poorest.

For education, in Eswatini, tertiary scholarships almost doubled and free primary grants received a 20% raise, but generally the priority across countries was teacher wages and recruitment, often squeezing other inputs. Health and education are emblematic of broader needs to increase the effectiveness of public spending among the five countries, where high per capita spend often buys relatively low outcomes.

Wage bill pressures may reduce capital spending

To maintain control over public finances and continue to make space for other budget priorities, all five finance ministries will need to carefully manage pressures to expand the public sector wage bill.

Recent wage bill momentum appears to be most significant in Botswana, where the 2023/24 budget for wages and salaries is 52% higher than 2019/20 (the lowest was 12% in Namibia). But higher inflation (and the allure of higher SACU revenues) makes this year particularly difficult and pressures to enhance pay, fill vacancies and create new posts are evident in nearly all the budget speeches.

The budget speeches suggest that most of the SACU countries are trying to limit pay increases in 2023/24 to below the level of inflation. Botswana has budgeted for a 5% pay uplift, and Lesotho for 2.5%, for example. The government of Eswatini has pre-emptively announced that it has budgeted for a 3% cost-of-living adjustment ahead of pay negotiations with labour unions.

South Africa has set aside funds to meet existing pay awards, but effectively ignored new pay negotiations. In a departure from past budgeting arrangements, the government was apparently treating these pressures as fiscal risks to be managed within the existing budget. The anticipated cost of the 7.5% pay increase agreed by unions and the government in March makes this a tall order.

Capital expenditures are often a casualty of in-year budget reprioritisation. Except in Lesotho, the 2023/24 budget speeches announced year-on-year increases in capital spending, but capital budgets in Botswana, Namibia and Eswatini remain below 2019 levels in real terms. Capital budget execution rates are also relatively low, as they are in many low and middle-income countries. Further pressures from wages increases won’t help.

Questions for the years ahead

If there is a common theme behind this year’s budgets, it’s that most are returning to pre-pandemic concerns expressed by finance ministers in the 2019 budget speeches: fixing electricity in South Africa, the shift to debt financing in Botswana, hefty capital expenditure increases in Namibia, efforts towards fiscal discipline in Lesotho and little fiscal space for meaningful new policy measures in Eswatini.

The latest round of budgets offers some signs of progress. Energy reforms in South Africa and new stabilisation funds for Eswatini, Lesotho and Namibia are particularly notable. But interest costs are up $7.8 billion, more than $110 per person, since 2019, for the region as a whole, and simmering payroll pressures present significant questions for the future:

Where will the resources come from if public sector pay agreements are unexpectedly generous? And will the smaller member states invest SACU windfalls effectively while shifting public spending profiles into more sustainable trajectories?

However, the most important question is for South Africa, and whether the biggest economy in SACU can kickstart growth to expand employment, raise public spending and lift prospects for the region. If not there will be more difficult budgets ahead.