Today the UK government’s new policy of mandatory vaccination for care home workers takes effect. By the government’s own reckoning this could result in up to 12% of workers in residential care settings leaving their jobs. How worried should we be about staff shortages in the care sector? In short, very.

How big are staff shortages in the care sector?

In August, Skills for Care – the UK’s care workforce development agency – reported that the adult social care sector had a vacancy rate of 8.2%, more than twice the UK average (3.7%, already the highest on record). The sector is facing a daunting shortage of 105,000 workers.

And the demand for care workers isn’t going away. Our rapidly aging population means we will need up to 627,000 extra care staff by 2030/31. This will require a monumental transformation in the way we train, recruit, and retain care workers.

Why are staff shortages such a problem?

Care work is notoriously undervalued. It is amongst the lowest paid occupations in the UK with nearly three-quarters of care workers earning below the real living wage. This is true for workers employed in residential care settings as well as for those delivering home-based care.

Unpaid working time is increasingly common, with many home care workers not paid for travel time between clients. Electronic monitoring systems in the homes of elderly clients ensure that many carers are only paid for direct contact time and often not when visits overrun their official schedules, eroding earnings further.

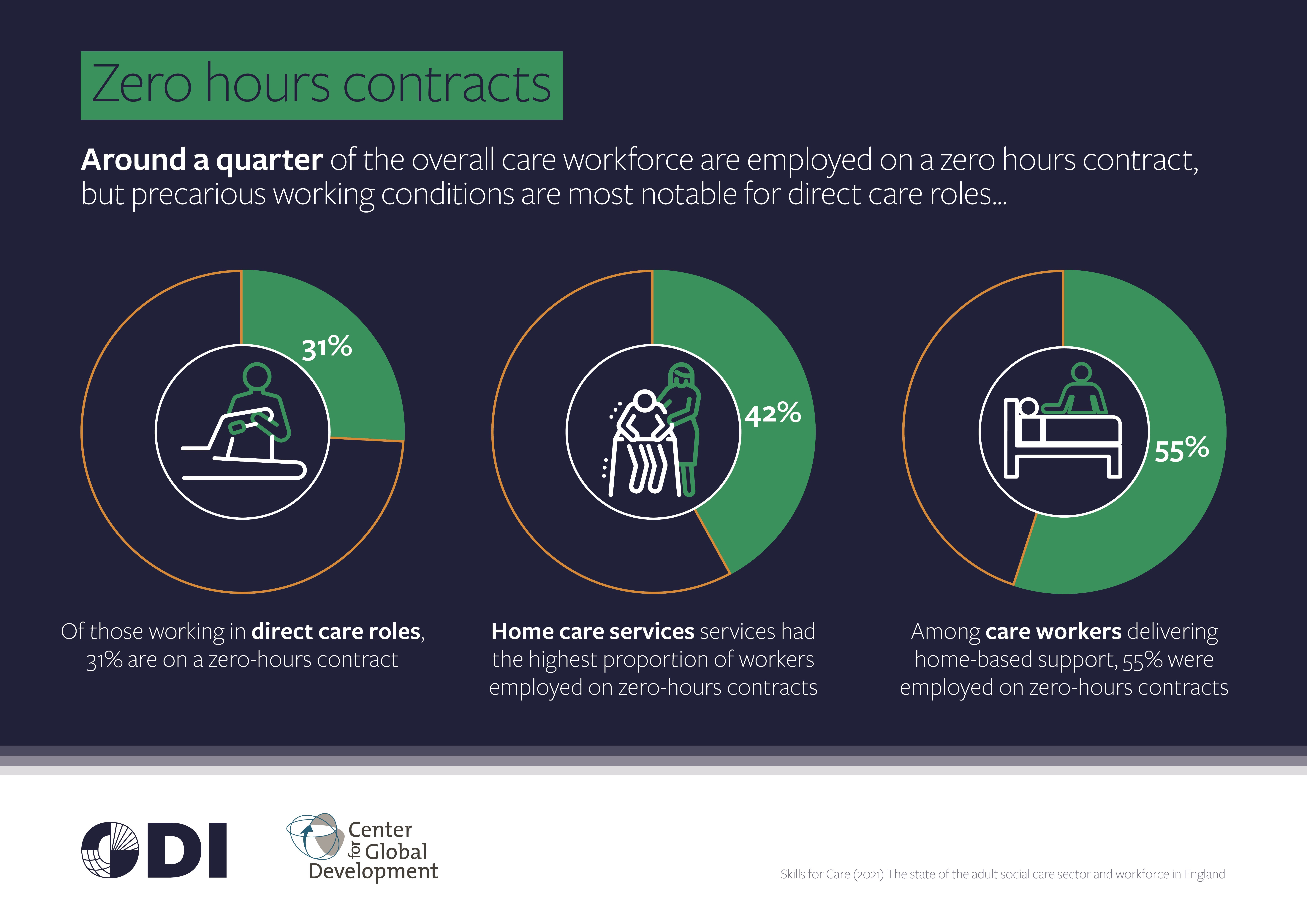

Around 55% of care workers delivering home-based care are employed on zero hours contracts. Often allocated extremely short time slots for home care visits (pdf), working conditions are stressful and inadequate to provide dignified care. Conditions in home care, in particular, are considered amongst the most precarious (pdf) in the British economy. Few will be surprised that care providers struggle to recruit and retain workers in such dismal circumstances.

Is there a Brexit-effect?

Migrant workers are incredibly important for the care sector, making up 22% of the workforce in 2020/21. These workers come from all over the world, including the EU.

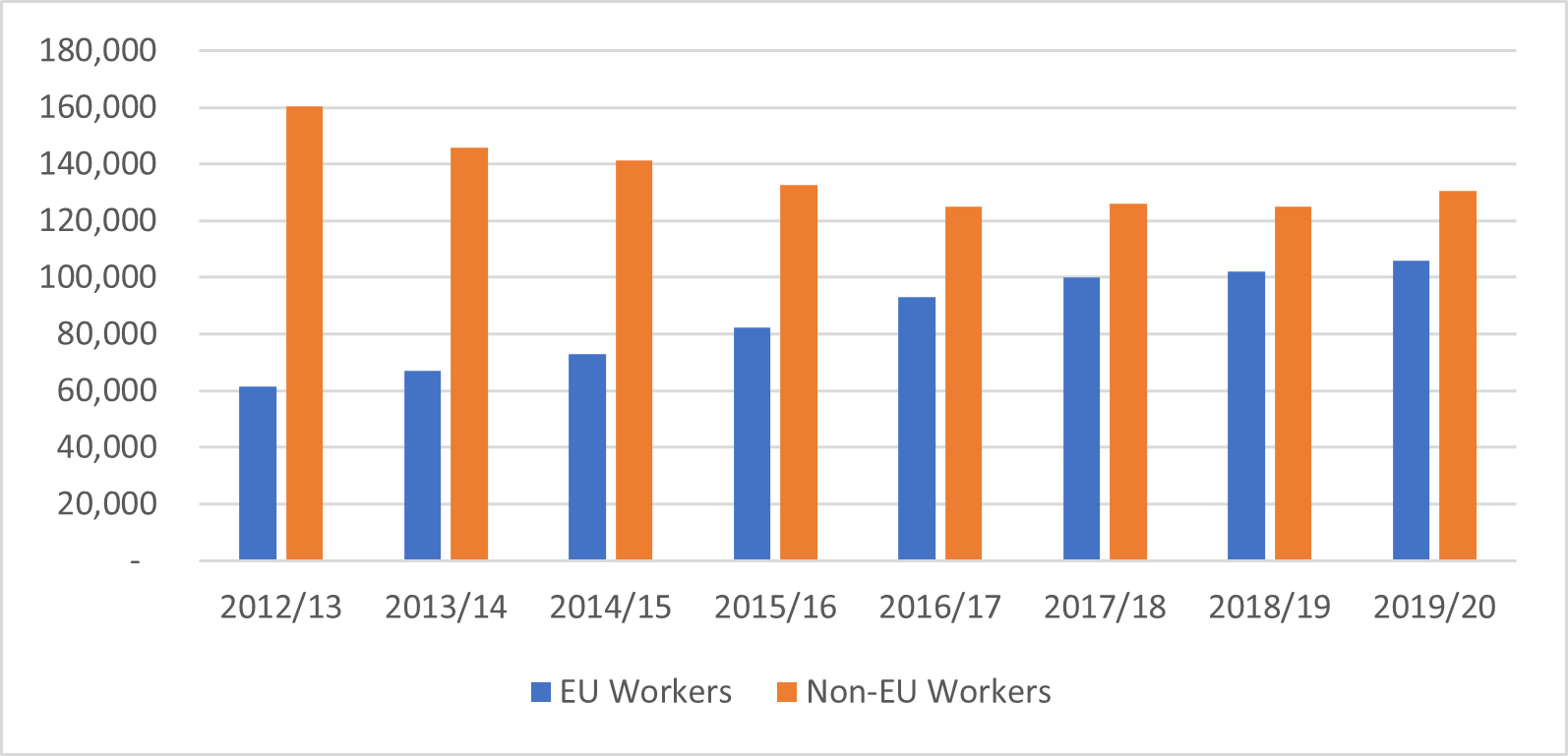

Given that UK immigration policy prior to Brexit provided limited access to workers deemed ‘low-skilled’ from outside the EU, we have developed a much greater reliance on EU workers over the past decade (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. European workers make up a large amount of our care workforce

Source: Skills for Care (2021) Workforce Estimates

So, are our current shortages due to Brexit? Certainly, when it comes to our health service, we have seen a dramatic decline in the number of EU nurses coming to work in the UK since 2016. The situation in the care sector is less striking, with a relatively small decline in the numbers of EU nurses working in long-term care (falling by 17% between 2017/18 and 2021/21).

Yet this is still significant given the occupation of registered nursing consistently has the highest vacancy rate in the care sector. However, it is also notable that other direct care roles have not been affected. Yet. Negative impacts are still widely expected, given Brexit will deprive us of this important source of new care workers in the future.

Can immigration help us respond to workforce shortages?

Our new points-based immigration system isn’t well set up to admit people labelled as ‘low-skilled,’ despite the vast need for such workers throughout our economy and society.

The system’s shortage occupation list admits people who reach defined skills levels and reduces the salary threshold required. While senior care workers were recently added to the shortage occupation list, most are unlikely to meet the reduced salary threshold under the points-based system. Wages – even for more qualified and experienced carers – are simply too low.

In addition, most care workers are employed below this level and therefore fail to meet the minimum skill level needed to apply under the shortage occupation list.

Therefore, our current immigration system is simply not set up to address care workforce shortages. Such an approach flies in the face of public support: 77% of the UK public supports recruiting migrant workers in key services, such as health and social care.

What are other countries doing to attract immigrants?

The UK is hardly unusual in this respect. Many European countries, such as Italy, Spain, and Germany, have even more rapidly aging populations than us and also face major workforce challenges. Migrants are hugely important to their sectors (for example, they deliver 89% of the home care in Italy) though many work informally and are undocumented.

Only a small number of countries have migration pathways specifically for the care sector. Where they do exist, they largely fail to deliver the number of workers required, and there are clearly design and implementation challenges.

Canada, for example, stands out with its Home Support Worker Pilot (HSWP) which includes a pathway to residency and citizenship. It operates alongside smaller programmes designed to attract workers to rural, remote areas.

However, Israel’s foreign care worker route – which has operated at significant scale since 1991 – is widely critiqued for exploitation and abuse of workers and offering no pathway to residency or citizenship (pdf).

What’s the way forward?

The UK care sector is repeatedly in the news, mainly in the context of impending crisis, the extended underfunding of the sector, concerns about deteriorating quality of care, or the government dragging its feet on reforms.

We already know we have a problem. What we don’t have is political recognition of the high public value of care work.

Caregiving is meaningful and skilled work. The care sector has growth potential, its jobs are ‘green jobs’, and it can be financed in a way that proactively shapes markets, using delivery models that build wealth in local communities. Despite all this, we’ve failed to put in place the necessary policy reforms to support our care workforce and the people who rely on a well-functioning care system.

So, what’s the answer? Undoubtedly, we need to increase public spending on care (far above the recently announced, inadequate, budget increase). We have to make care jobs decent jobs and address precarious working conditions and raise wages.

Critically it also means reforming the commissioning model used by local authorities that, as assessed by the Fair Work Convention in Scotland, contributes significantly to driving down wages and working conditions.

Meanwhile, we need more workers immediately. We needed them before the vaccination mandate and we need them now. We cannot resort to volunteers being drafted into care homes and we certainly cannot stand by while people with disabilities fail to find care workers to support them to live independently with dignity.

The government has already been forced to open up a new immigration route to respond to the truck driver shortage. Implementing a Canada-like route providing decent work opportunities to migrants may be an option to address immediate challenges.

We also need to be clear. These shortages are not going away and workforce challenges are only set to grow. Ultimately, investing in improving the sector, alongside attracting migrant workers, is the only way we will be able to provide safe and high-quality care for our elderly population.