Dominant narratives on migration often paint a simplistic picture of human mobility and pave the way for the demonisation of migrants.

On International Migrants Day, and always, we must contest the foundations of these harmful narratives. Here, we shed light on five common misconceptions of anti-migration discourse and policy-making.

Narratives

Despite the prominence of migration and circular mobility in the so-called global South, South-North flows are often the focus of UK/ EU narratives on migration. Often overlooked is the fact that migration between countries of the global South accounts for nearly half of international migration globally, and up to 70% in some places. Additionally, low- and middle-income countries host 85% of refugees and almost 100% of internally displaced people.

This unequal emphasis on migration towards the global North brims with colonial undertones and exposes a simplistic understanding of human movement. Unchecked, these narratives influence the direction of migration policy and reinforce power asymmetries. Indeed, in centring the narrow interests and biases of global North actors, rather than the realities of those the move across the world, we pave way for the dangerous, dysfunctional, and ineffective migration policies we see today.

In re-shaping the story on migration, we can contest the narratives that demonise migrants. Let’s begin by centring the hopes, decisions, and experiences of those on the move, as well as the interlinking impacts of migration, inequality, and development that shape journeys across the world.

Aspirations

The MIGNEX Case Study Brief Series offers insight into the thoughts and feelings of young adults across 10 countries in Africa, Asia and Europe on the prospect of migration. Our research shows that people’s mobility decisions are not as simplistic as often depicted in political narratives and that there are many interconnected aspects that influence aspirations, intentions, and ability to migrate.

We found that international migration aspirations are not such a widespread occurrence as often portrayed: many young adults expressed a strong connection with the local area where they live and a feeling of hope for its future, with little desire or intention to move. Many would prefer to migrate internally, or to a neighbouring country, due to local opportunities, cultural or personal factors such as speaking the same language, with the possibility of visiting family and friends more regularly. For instance, in Erigavo, Somaliland, 69% of surveyed young adults prefer to stay, largely due to work and educational opportunities available in the country. In Dialakoro, a town in Eastern Guinea, 70% of surveyed young adults would prefer to stay in Guinea in the next five years or migrate to neighbouring countries Mali, Burkina Faso, or Ghana. Migration to Europe and the U.S. was in many cases rare and undesirable, particularly when weighing up the potential risks.

Decisions

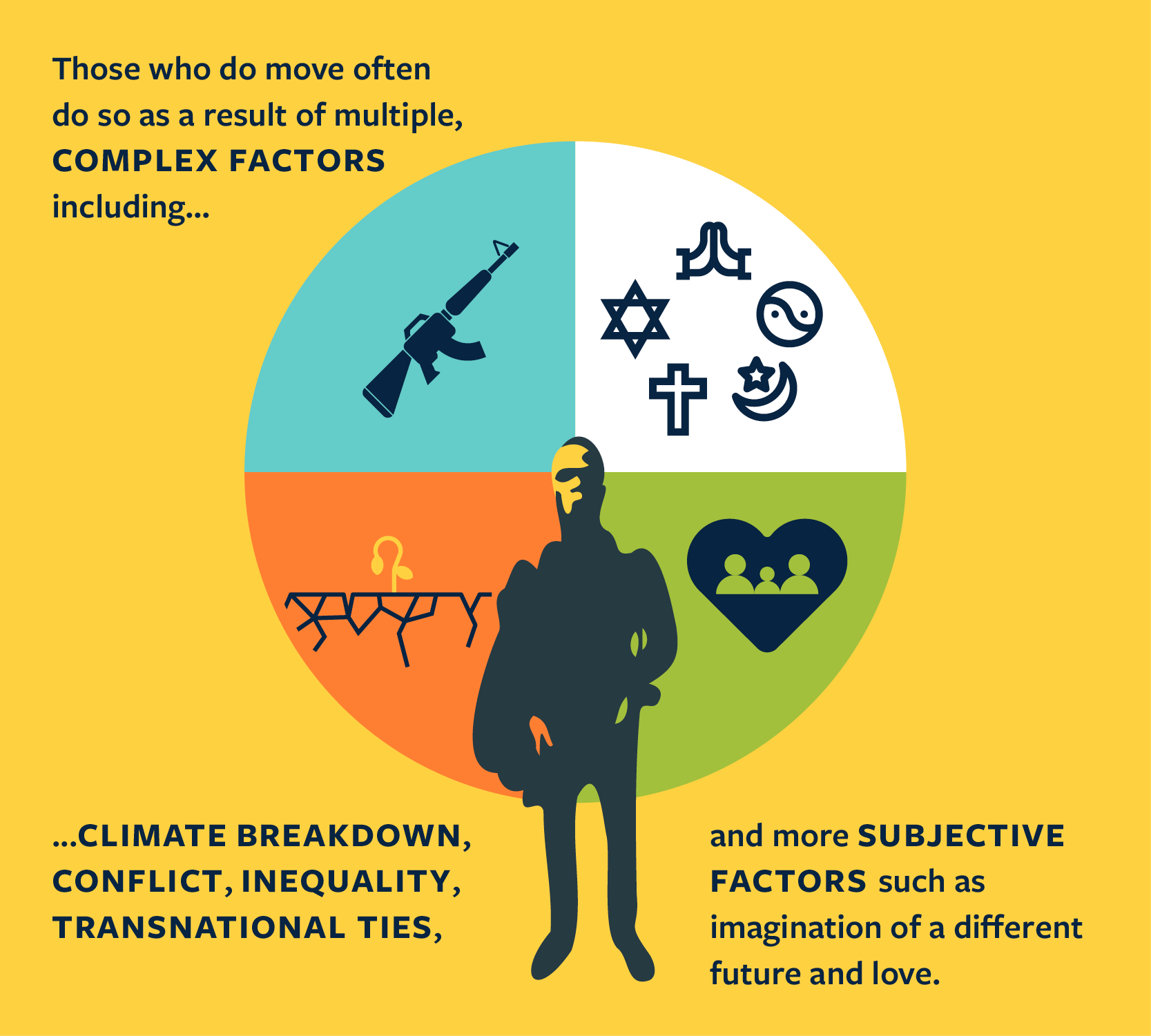

A common assumption is that ‘once people decide to move, they move’. Actually, it is possible to tell aspirations and plans for migration apart, with many interconnected factors influencing aspirations, intentions, and ability to migrate.

Even in instances where migration offers a critical, necessary lifeline, it is rarely an easy or feasible alternative. Existing inequalities at the local, national, and global level determine the ability to migrate, and the journey taken. For instance, the percentage of participants with a valid passport in the MIGNEX survey was low, ranging from 4% in Dialakoro, Guinea to 27% in Redeyef, Tunisia. International visa requirements per country reflect the colonial structures that shape migration policy, with those from the Global South often prevented or hindered from moving. In Afghanistan, imminent risk to lives ahead of the fall of Kabul, deteriorating security and high unemployment meant that international migration aspirations were high. Yet for many, the right to mobility remains contested due to barriers to mobility schemes, humanitarian corridors and legal identity.

Our research also examines how subjective factors, such as beliefs, emotions and feelings, shape and influence decision-making, showing that the assumption that migrants move to improve their economic status is only one small part of the story. MIDEQ - Migration for development and equality brings to the fore migrants’ perceptions, knowledge, and decision-making in the context of South-South migration, specifically for the migration corridors from Haiti to Brazil, from Egypt to Jordan, and from Nepal to Malaysia.

Displacement

Our research on Social protection responses to displacement shines a spotlight on the case of Colombia, which hosts the second largest internationally displaced population in the world (over 2 million displaced Venezuelans), alongside one of the largest populations of internally displaced people (IDPs) globally (8 million, over the course of its internal conflict). Despite these vast numbers, Colombia has adopted among the world’s most progressive policies towards both IDPs and Venezuelans. Although many challenges remain, IDPs have preferential access to social protection services to support them in overcoming the devastation that conflict has caused to their lives. Venezuelans with regular status are granted the right to work and a 10-year residence permit that allows access to health, education and various social protection services. These progressive measures have been labelled “an example for the region and the rest of the world”. They also recognise the substantial benefits that Colombia can achieve from effectively integrating Venezuelans into their economy and society.

While there is still a need to take heed of social concerns by implementing this progressive response alongside enhanced support for other vulnerable populations, rigorous evaluations are already starting to demonstrate the impressive results of Colombia’s displacement policies. These studies provide important evidence of the gains that can be accomplished from recognising and supporting the potential of displaced children and families – not only for those directly affected, but for the wider host population, government and economy too.

Policy

Across Europe, increasingly hostile and polarised political environments have culminated in a marked shift towards a more restrictive regime of migration policy, at least with respect to certain populations from the global South. But these policies often fail to reach their intended goals: migration continues to take place with migration restrictions and barriers just making migration more risky and expensive.

One explanation for this perceived policy ‘failure’, can be because of misplaced underlying assumptions about how people encounter and engage with migration policies. In many cases such policies assume that migrants have ‘perfect’ information and understanding of the existence and aims policies, whereas in practice knowledge and understanding is often patchy and varied. Our research provides nuance on how migrants’ encounter, and understand migration policies, and their awareness, perceptions and reactions to such policies. Our research shows that policy can undergo further ‘transformation’ in the minds of those it intends to influence, once implemented, and does not necessarily always result in the intended migration outcomes. Frequently, migration policies only play a minor role in decision-making compared to other factors. By shifting the focus on looking at what factors and processes actually matter in migration decision-making, we can contribute to more effective and coherent migration policies.