This set of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) focuses on how oil and gas relate to energy access and energy poverty. They cover the meaning of these terms, how they are measured and tracked, how energy access is necessary to escaping poverty, how oil and gas contribute to and detract from the achievement Sustainable Development Goals, and the alternatives that are available now and will be in the future.

What is energy poverty?

What do we mean by energy access and energy poverty?

At its simplest, ‘energy access’ means people having energy services (i.e. the combination of supply infrastructure, appliances and fuels) that help them meet their basic needs for a decent life. As well as being physically available, these services must be appropriate to the local context, affordable, reliable, safe and sustainable. When we refer to people living in ‘energy poverty’, this does not mean they have no energy services. People may cook on open flames or simple wood- or charcoal-fuelled stoves. They may light their homes with candles and kerosene lanterns. They may have sporadic access to electricity at home, at work or in public buildings in their community such as schools or health centres. Yet, they are ‘energy poor’ because they are forced to use sources of energy that are unreliable, unhealthy or unsafe, costly (in terms of money or time) or, often, all of these things.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 is that everyone should have access to modern energy services (i.e. electricity and modern cooking technologies) by 2030. This is linked to many of the other Goals because of the direct and indirect benefits that energy access provides for combating poverty, inequality, poor health, climate change and environmental degradation.

The most common concept of energy access/poverty focuses on the use of electricity and cooking fuels within households. This is a useful starting point, but it misses much of the picture. For example, relatively little attention is paid to how households heat water or how they maintain comfortable household temperatures (heating, cooling, or both). Energy also delivers some of its most important benefits outside the home. (For further discussion, see FAQ 1.3). First, energy is vital for powering services within communities, such as health clinics, schools and local businesses. Second, energy used for transport is also key to escaping the ‘poverty trap’ by allowing movement of people, goods and information between communities.

How do we measure energy access?

Global progress on energy access is measured using simple yes/no surveys, but approaches analysing the different aspects of energy access are slowly starting to appear.

Progress on SDG 7 is currently measured by binary assessments of physical infrastructure within households: does the household have an electricity connection and do they use clean fuels and technologies as their main means of cooking? ‘Clean cooking’ is interpreted as a mixture of fuels and technologies that does not result in emissions of carbon monoxide and soot (particulate matter – PM 2.5) that exceed the limits set by the World Health Organization (WHO). In practice, this means: stoves that use electricity or gaseous fuels such as LPG, natural gas or biogas; liquid alcohol fuels; and solar-powered cookstoves. In the future, advanced cookstoves that burn solid fuels much more cleanly than traditional fires may also be included.

This is a good start, but it tells us nothing about the quality of energy access for these fuels nor about other energy needs inside and outside the home. Over the last decade, research and advocacy work have moved the discussion on to better reflect the different dimensions of energy access and how they fit together.

As part of a reconceptualisation of energy access, the World Bank developed the Multi-Tier Framework for Measuring Energy Access (known as the MTF; see pages 6 – 14) to better understand the quality of different types of energy services that people have access to at home and in their community. The MTF defines energy access as ‘the ability to avail energy that is adequate, available when needed, reliable, of good quality, convenient, affordable, legal, healthy and safe for all required energy services’. Rather than posing a simple yes/no question, the MTF surveys ask households about their energy use and evaluate household access to electricity and clean cooking across different dimensions using two separate, six-tier systems. They also consider energy access for community services and productive uses.

As of 2020, MTF surveys have been carried out in only 16 countries, so global tracking of energy access progress against SDG 7 involves several international agencies combining these surveys with standard binary assessments in the annual Tracking SDG 7: The energy progress report. The findings of the 2020 report are discussed in FAQ 1.2 below.

How many people live in energy poverty and where are they?

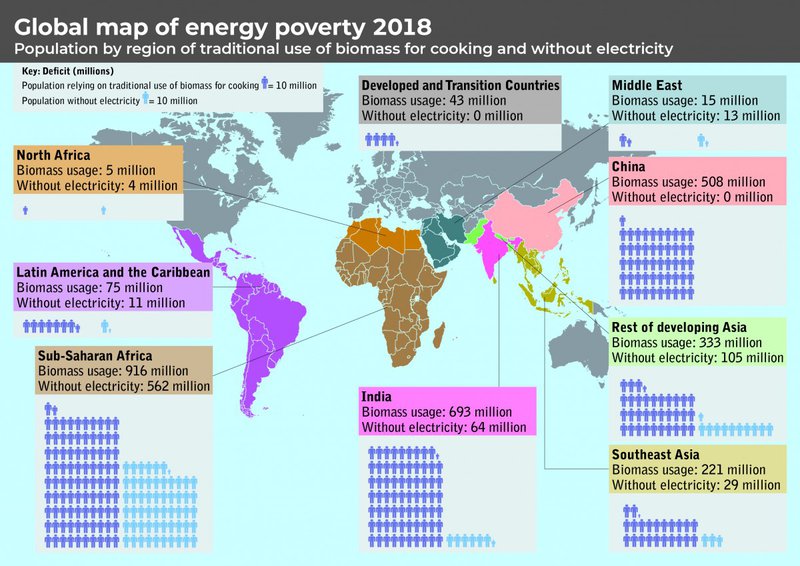

In 2018 (the latest data), 789 million people did not have access to electricity and 2.8 billion people did not have access to clean cooking technologies. Most of these people live in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (see map below).

The 2020 Tracking SDG 7 report shows we are not on track to provide universal access to modern energy services by 2030. Many people who are deemed to have access still face challenges in using these services in their daily lives, and access to energy is highly unequal. The difference between countries’ populations means we need to look at both the percentage and the absolute number of people with access to understand the data. Some countries have particularly low rates of access while others, because of their large populations, have high numbers of people without access. The Sustainable Energy for All initiative (SEforALL) highlights those high-impact countries (HICs) which account for the overwhelming majority of people without access to energy globally. HICs for electricity do not overlap directly with HICs for clean cooking. However, in both cases, rural populations are less likely to have access than their urban counterparts. In all cases, the headline numbers reflect a basic understanding of access. Levels of access to modern energy services that are affordable, reliable and safe are likely to be considerably lower.

Electricity

More than one billion people have gained access to electricity since 2010 and, in 2018, 90% of the global population lived in a household with an electricity connection. Nonetheless, 789 million people did not and on current trends, 620 million people will remain without access in 2030. Electrification rates vary significantly within and between countries. Globally, the electrification rate for rural households (80%) is much lower than that for urban households (97%) and 85% of people without access to electricity live in rural areas. More than two-thirds live in sub-Saharan Africa where 60% of the population live in rural areas and the national average access rate is less than 50%. The 20 HICs with the most people without access to electricity are all low- and lower-middle-income countries in Africa and Asia.

MTF surveys also show that having an electricity connection does not guarantee access to electricity. The 2019 Tracking SDG 7 report noted that in one-third of the HICs the power grid would fail at least once per week, and in half of them 40% of their populations could not afford to consume a basic quota of electricity.

The emerging MTF surveys (see FAQ 1.1) are beginning to illustrate the complex relationship between gender and electricity access. There is no universal pattern. In some HICs, access rates are higher for male-headed households while in others they are higher for female-headed households. Even national generalisations can be misleading: in Cambodia, for example, female-headed households have higher access rates than their male counterparts in urban areas but lower rates in rural areas.

Cooking

We have made almost no progress in reducing the number of people without access to clean cooking fuels and technologies in the last two decades. Limited gains in percentage terms have been cancelled out by increasing population. In 2018, 63% of the global population had access to clean cooking fuels and technologies while 2.8 billion did not. Even if all current policies are implemented, 2.3 billion people will still lack access to clean cooking by 2030.

The variation between and within countries is even more stark than for electricity. Of those without access to clean cooking in 2018, 44% lived in China and India. Within countries, 83% of urban households have access while the figure is just 37% for rural households. In the 20 HICs for cooking, 17 have access rates below 50% and in six countries this was less than 5%.

Having a clean means of cooking does not guarantee that a household will use it for all cooking needs. So-called ‘stacking’ occurs when a household uses different fuels or appliances at different times or for different cooking needs. Stacking is found in all households in all countries, but stacking that includes traditional energy sources, such as open fires and improved cookstoves to cook different foods, can undermine the benefits of using clean fuels and technologies.

The barriers to sustained uptake of clean cooking solutions vary widely and there is no single way to overcome them. Ensuring availability and affordability of clean fuels can be challenging in areas with weak supply chains or where household income varies from month to month. Socio-cultural factors such as entrenched gender inequalities and preferences for particular foods and cooking methods can also impede universal access to clean cooking. Women and children pay a disproportionate price for lack of access to clean cooking, both in terms of their time and their health, yet it is adult men who mostly make decisions related to buying clean cooking energy services. Progressive work by governments, donors and civil society is highlighting how a combination of targeted interventions is often needed to overcome these barriers.

How does access to modern energy services help to reduce poverty?

A lack of access to energy is one of the many, interlinked dimensions of poverty. Key links between energy access and aspects of deprivation are covered here and in FAQ 2, which looks at its relationship with income poverty.

In 2019, building on years of research, the UN stated that ‘human survival and development depend on access to energy’. Access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy (SDG 7) is positively correlated with every other SDG and is imperative for limiting global heating to 1.5ºC. At the same time, energy poverty can act as a multiplier of other sources of deprivation, undermining other development or humanitarian efforts.

How access to energy services can help people escape from poverty depends on many factors including their needs, where they live, their daily activities and the appliances they own. The multidimensional nature of poverty means that few of the benefits of energy access are automatic and must be accompanied by interventions that address other aspects of deprivation. In practice, this means that, to improve lives, energy services must be tailored to local contexts and the varying needs of different end-users.

Within households

Access to electricity is correlated with the Human Development Index (HDI). Households can light their homes, allowing children to study and home-businesses to work at night, without being exposed to air pollutants from non-electric and unsafe lighting sources (e.g. kerosene lamps). Electric fans and air conditioning units can cool houses, and charging mobile phones and powering entertainment systems promote social inclusion.

Clean cooking fuels and technologies can eliminate the pollutants produced by traditional stoves and reduce the four million deaths a year in low- and middle-income countries linked to indoor air pollution. Typically, clean cooking technologies are inherently safer and much more efficient. This allows women and children to reallocate time spent collecting fuel and cooking to other activities, potentially leading to improved gender equality if combined with other interventions. Switching to affordable and reliable purchased fuels can also give households more control over the energy they use, which may be particularly important in fragile contexts or displacement camps where freedom may be limited and fuel collection dangerous.

Within and between communities

At the community level, electricity powers: streetlights, making people feel safer; lights in businesses, allowing them to stay open later; medicine-storing fridges and medical equipment in health centres, improving health care; and ICT equipment in schools and government buildings. Electricity can also reduce the need for manual labour by powering shared community services such as a water pump or agricultural processing equipment.

Energy is also essential for connecting communities: globally, one of the most important uses for energy is transport. Those without access to powered transport are much more likely to be caught in the ‘poverty trap’, with limited access to other people, goods and services. In cities and rural areas alike, access to transport helps to: provide consumers and businesses with access to markets; promote employment, education and healthcare opportunities; and combat social exclusion.

How are oil and gas used by people living in poverty today?

Historically, fossil fuels were the only means available for those living in poverty to have access to modern energy services. Although alternatives are now available (see FAQ 1.5), many people living in poverty continue to use fossil fuels. To achieve universal energy access while limiting the average global temperature rise to 1.5ºC, we must ensure that sustainable alternatives to oil and gas are available to people living in poverty.

There are three main ways in which the consumption of oil and gas can meet the needs of people living in poverty today: for cooking, for electricity generation and for transport.

Cooking

Within households, natural gas and LPG are widely used as a versatile cooking fuel that can quickly deliver a range of temperatures. Poor people in rich countries may use natural gas to cook but in poorer countries it is usually only available in relatively affluent urban areas. LPG is widely available in many developing countries, and subsidies have often been governments’ main tool to provide universal access to clean cooking solutions. However, general subsidies tend to be regressive because they benefit richer households (who consume more energy) than poorer ones. Nonetheless, subsidised LPG in portable and durable cylinders has permitted its broad distribution to many poor households, including in remote areas.

Electricity generation

Natural gas and oil are used to produce electricity in many countries (see FAQ 2). The benefits that access to electricity provides to people living in – and escaping from – poverty are a result of the services that the electricity provides, not the fuel that was used to produce it. Oil is also used in many developing countries to power back-up generators but these are expensive to buy and costly to run, meaning they are unlikely to be owned by people living in poverty.

Transport

Oil and gas power nearly all of the world’s transport sector. People living in poverty are unlikely to have their own motorised transport (e.g. a car or motorbike) but may use public or informal transport options (e.g. buses or local taxis).

Are oil and gas cost-effective solutions for providing access to electricity to those who do not have it?

This is not the case for most people without access to electricity today.

How we generate electricity, the stability of electricity provided by the grid and how households gain access to electricity are changing. The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Sustainable Development Scenario projects that the most cost-effective way to ensure universal access to electricity by 2030 results in only a quarter of households that gain access doing so via fossil fuel-powered electricity. The continued development and decline in costs for renewables, battery storage and other non-technology aspects of electricity supply (i.e. planning, construction) for on- and off-grid could easily mean this figure falls further.

Burning oil and gas has negative health and environmental impacts, including air pollution and breathing problems (see FAQ 3), but, especially before the time of thorough environmental impact assessments, these were often overlooked because oil and gas were the cheapest option available. Technology development and demographic changes, as well as greater awareness of those negative impacts, mean there are now three main economic reasons why oil and gas – and coal – are not the first choice for improving access to electricity:

1. Most people without electricity live in rural areas where the cheapest way to provide access is usually via off-grid or distributed renewables.

Historically, most people have gained access to electricity via grid expansion in urban areas, the cheapest way to provide electricity to densely populated areas. However, 85% of those without access to electricity live in rural areas (see FAQ 1.2) where it is usually cheaper to provide access to electricity via decentralised systems such as mini-grids and standalone home systems. Recent modelling has shown that providing access to electricity for more than half of those households that currently lack access will be achieved most cost effectively via decentralised options. Older mini-grids are sometimes powered by diesel, with the cost sometimes subsidised by the government. However, as with grid-scale generation, diesel is often no longer the cheapest power option. Renewable-only and hybrid mini-grids are increasingly more competitive and their costs could fall by a further 75% between 2016 and 2025.

2. For those gaining access via grid connections, renewables are now the cheapest and most common way to add new power.

Historically, households gained access via grids that were powered by fossil fuels because these were the cheapest way to generate large amounts of electricity, despite their negative environmental and human health impacts (see FAQ 3). The breathtaking reduction in cost of large-scale wind- and solar PV-power generation over the last decade means that renewables are now the cheapest source of large-scale power for two-thirds of the global population. For example, solar PV is the cheapest way to add power to the grid in India, Guatemala and Ecuador, while onshore wind is the cheapest in Peru, Kenya and Morocco. This is not news to those in the energy world: most new power-generation capacity added each year since 2015 has been renewables and in 2017 more solar PV capacity was added than all fossil fuels combined.

3. Oil-powered back-up electricity generators will be increasingly redundant as grids become more reliable and the cost of standalone renewable systems falls.

Where the electricity grid is weak or non-existent, richer households and businesses generate their own power from mini-generators that run on gasoline or diesel. As well as being a major source of local air and noise pollution (see FAQ 3), these ‘gensets’ are substantially more expensive than grid-based electricity in every part of the world. However, they are widely used because they were the only option to ensure a reliable electricity supply and fuel was often subsidised. Two key trends are changing this. First, in many countries the frequency and duration of electricity blackouts are decreasing (see FAQ 2), reducing the need for back-up power. Second, falling costs for renewable and battery technologies and global efforts to remove fossil fuel subsidies mean that clean alternatives such as integrated solar PV and battery systems can already compete on cost terms.

Isn’t gas the only feasible option for clean cooking?

LPG and natural gas will be important options for providing clean cooking in developing countries over the next decade. Yet, thereafter they are projected to be overtaken by non-fossil energy sources, such as biomass, which will already constitute half of all clean cooking solutions by 2030.

Irrespective of the clean cooking fuels and technologies available, their uptake will require policy and other interventions, including different financing approaches. Alongside market-based solutions, governments will need to create Energy Safety Nets that target poor and vulnerable households with both financial and behavioural change support, to ensure they are not left behind.

The next ten years: meeting SDG 7

Half of the population in developing countries use non-fossil sources of clean cooking in 2030 under the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario. This will require a mixture of fuels and technologies depending on context, economics, natural resources, infrastructure and cultural factors. In grid-connected urban areas, the best option may be electric cooking, which is already the fuel of choice for 32% of urban Ethiopian households and 80% of all households in South Africa. In rural areas, improved biomass cookstoves are the most important technology, but the use of biogas and liquid biofuels also grows. Some cooking needs can also be met by non-fuel technologies. For example, solar ovens can cook foods that require lower temperatures over longer periods and have no costs once the upfront capital costs have been paid.

Approximately half of households using traditional cookstoves today are likely to gain access to clean cooking via LPG. This means that about half of the population in developing countries is projected to cook with a fossil fuel in 2030. This includes the use of natural gas by relatively affluent households but LPG remains the most important fossil fuel for increasing access to clean cooking for poor people. In urban areas, higher population densities and economies of scale can justify the necessary supply infrastructure costs, but market-rate LPG is still unlikely to be affordable for many of the poorest in society, hence the need for Energy Safety Nets.

Balancing the climate crisis against the need for LPG for cooking access by the poor

The use of LPG for cooking emits greenhouse gases which contribute to global heating and the climate crisis. However, the magnitude of these emissions is minor compared to those from fossil fuels used in other sectors (see FAQ 3); some argue that the emissions of LPG are offset by the avoided emissions from collecting and burning biomass. Nonetheless, the use of LPG for cooking by poorer people now and in the near future cannot legitimise other uses of fossil fuels, or lock households and countries into fossil fuel infrastructure. LPG is only a minor by-product of natural gas processing and crude oil refining, and cannot justify investment in further, large-scale gas exploration or production activities.

Beyond 2030: clean cooking without LPG or natural gas

There is no technical reason why the transition from cooking with fossil fuels to cooking with clean electricity and renewables, already on-going in many parts of the world, will not continue beyond 2030. Most developed countries – and some developing countries – have already begun discussing how to move away from cooking with fossil fuels. In Ecuador, for example, the government is already working to transition households from LPG to renewable-powered cookstoves. There are also opportunities for technologies that use sustainable, local, renewable fuels instead of fossil fuels. For example, today we use just 6% of the global sustainable biogas potential and even conservative scale-up estimates suggest 200 million people could gain access to clean cooking via biogas by 2040.

Andrew Scott and Sam Pickard