Many are keen to leave refugee camps and support themselves

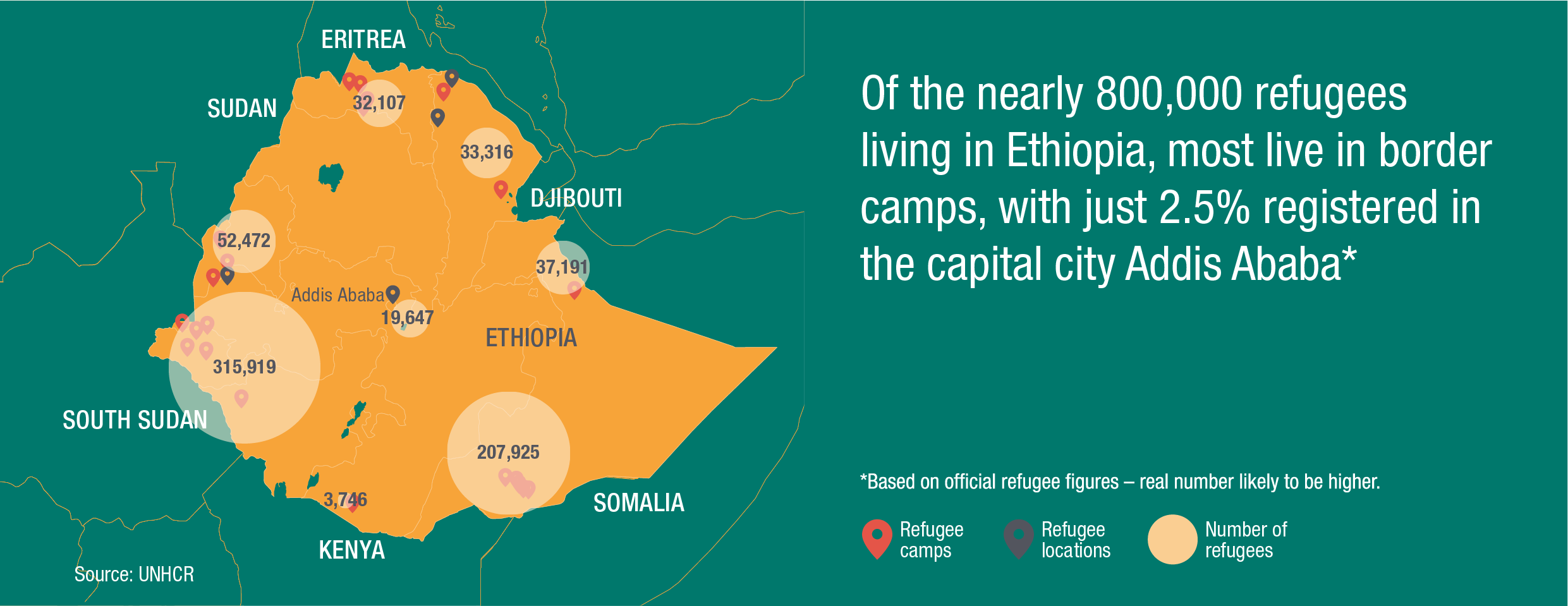

Refugees are largely confined to the camps where there is little work and few opportunities for legal onward movement. Of the nearly 800,000 refugees living in the country, most live in border camps, with just 2.5% registered in the capital city Addis Ababa. Only people with serious medical needs, refugees at risk within the camps and financially secure Eritrean refugees are permitted to leave.

Since 2010 the government has operated a special ‘out of camp’ policy for Eritrean refugees, which allows them to leave the camps and live in urban areas. But to qualify they must have a relative able to financially support them or enough money to support themselves.

All this could change. At the UN summit on refugees and migration in September 2016, the Ethiopian prime minister promised to improve conditions for refugees in the country. This effort will include allowing more refugees to leave the camps and find work.

Meanwhile, the lack of opportunity within the camps makes an already mobile population restless. There are some livelihood programmes provided by several NGOs but these are oversubscribed and there aren’t jobs for people to move into.

Sham Alem’s mother Azeb took part in a course in hairdressing, but she can’t afford to buy materials to get the business started. Another young mum living in Adi Harush, Freweyni, secured a loan to start a mobile phone charging business. She charged customers 1 Birr per charge, enough to provide her with some extra cash to feed her three children. However, when someone stole the phones, she was left in debt and was forced to close the business.

Many of the young people at Adi Harush study carpentry, computer studies and mechanics, but again, there are few jobs for them to utilise these skills. In 2015, the Jesuit Refugee Service set up a centre where they combined art, music, drama and other creative classes with social work for the younger refugees.

This has been more successful. One reason is that the Ethiopian government permits Eritrean refugees to work casually in the creative industries, earning money by performing at weddings or in bars.

Journeys on hold: Teddy's story

It has also provided jobs in the camp for refugees with skills in music and the arts. Asmelash has started teaching drama and dance on weekdays at the centre, a short walk from his hut. Teaching children and young adults has given him a sense of purpose. He uses his acting skills and knowledge, while also using his own lived experiences of the regime and trauma of onward movement. Working with social workers and teachers, Asmelash has developed ways to use the lessons as therapy for the younger refugees.

What could be achieved if the right support and policies are in place

Refugees are not allowed to work in Ethiopia, making it hard to build a future in the country. The Ethiopian government’s promises made at the UN summit last autumn included 30,000 jobs for refugees through the creation of two industrial parks, partly funded by the EU.

Jobs are needed, but so is a systematic reform of the process for managing refugee flows in Ethiopia, according to NGOs and officials working in the country. In its report on the onward movement of refugees in Ethiopia (PDF), the Danish Refugee Council and UNHCR recommend livelihood programmes include recreational and entertainment activities alongside improved education provision. The report also says livelihood policies need to work with refugees to tailor provisions. Ahmednur Abdi, country director for the Norwegian Refugee Council, says it is important to recognise the difference between camps and respond accordingly. If the camp is stable, NRC focuses on sustainable intervention. But in more unstable spots, they think more creatively.

Key recommendation: ensure skills training for refugees is relevant to the local context, and expand the range of opportunities on offer.

Part of thinking creatively is asking refugees what they need. This is perhaps why the music and arts centre has been so successful. For many of the students, it is the first time they have been able to develop something they enjoy. It sustains their interest giving them time to consider their options and make informed decisions, rather than leave Ethiopia immediately. There is also the possibility of work. Some of the students have already performed in local shows.

For young refugees with academic potential there is need to provide better quality education or at least access to universities and other higher education colleges.

‘There are a lot of people who can do a lot of things, who have good abilities.’

The untapped potential of refugees is something Yesuf spends much of his time thinking about. ‘I want organisations which are supporting all refugees to look at us deeply. There are a lot of people who can do a lot of things, who have good abilities.

‘My friend has no financial support but he is so brilliant in having ideas. Creating things that are different. He didn’t have a mobile phone. He couldn’t even pay for his rent. JRS gave him a laptop. For most of the jobs he wanted to do he needed a laptop.

‘There are a lot of people that I know that have a good ability to do a lot of things. I applied with my friend, she is Yemeni, to be photographer. I am so interested in nature. To take special photos.’

The two young adults went along to UNHCR asked if they could get a grant to buy a camera. Yesuf smiles. ‘They said, ‘OK we will think about it.’

Key recommendation: support refugees and migrants with access to work, education and creative opportunities.

Frequently asked questions

Credits

Credits

This web story was funded by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation and based on research by Richard Mallett, Jessica Hagen-Zanker, Nassim Majidi and Clare Cummings. It was written by Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi with photo and video by Gabriel Pecot, infographics by Sean Willmott, and with thanks to Helen Dempster, Jessica Zarins, Ailin Martinez and Pia Dawson.