Why Eritreans leave

In a small classroom in the Adi Harush refugee camp in northern Ethiopia, a dozen or so young Eritrean refugees perform a play. It is a love story, drawing on elements of traditional Eritrean storytelling, with singing, dancing and physical comedy. Tesfay, 24, is the young Romeo. Though slight in stature, his blue jeans hanging from his hips, Tesfay fills the makeshift stage, belting out his longing in a high clear voice. Off stage Tesfay is shy, withdrawn as he explains why he left Eritrea, the country of his birth.

‘I was good in school but I was forced to go to the military,’ he said. ‘I came to Ethiopia because you cannot live in Eritrea, you cannot do nothing but go into the military. The system is oppressive.’ The army officers in charge promised him 15 days leave, but it never materialised. By the time he was 19 he had served two years and still not seen his family. And so like hundreds of thousands of Eritreans, in 2011 Tesfay escaped, taking the well-trodden route across the Marab River into Ethiopia.

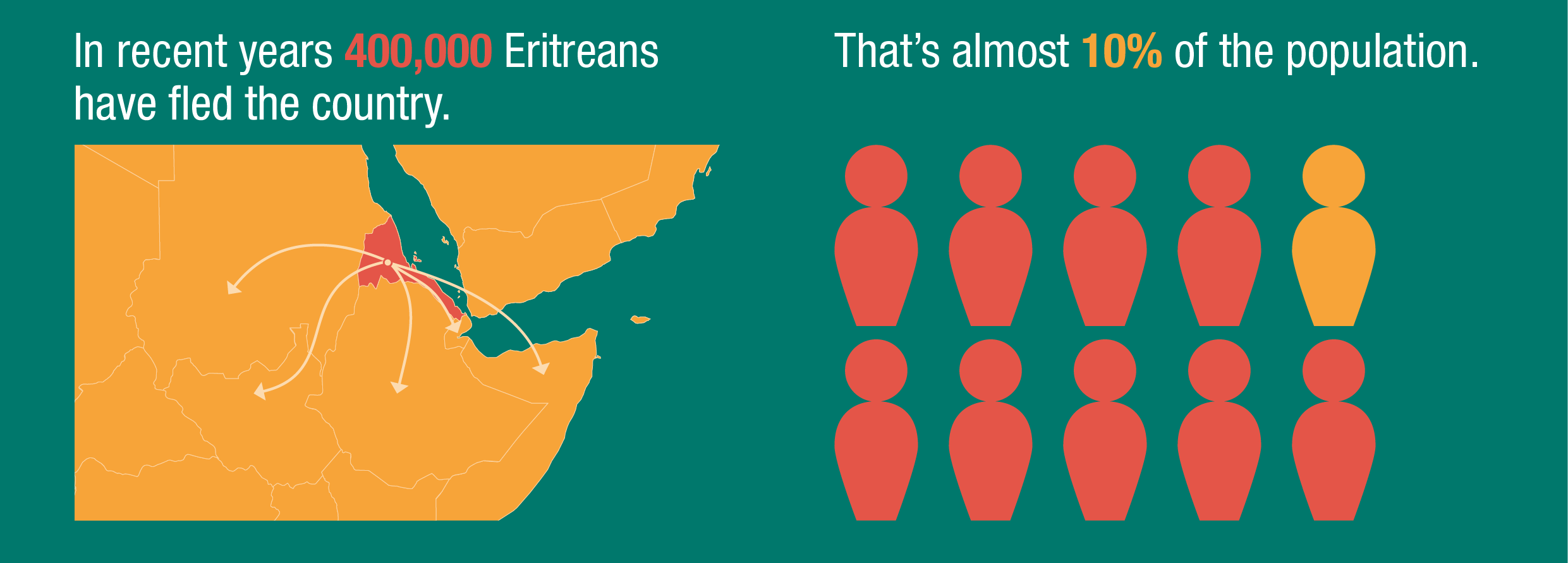

In recent years, 400,000 Eritreans, almost 10% of the population, have fled the country. Most cross borders into Djibouti, Ethiopia or Sudan, driven to leave for a myriad of reasons. Last June the UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea published more evidence of crimes against humanity committed in Eritrea by state officials. Witness statements suggest that enslavement, detention, rape, forced indefinite military conscription and other abuses are widespread. A restricted economy offers few opportunities.

When leaving Eritrea, refugees with connections or money often take established migratory routes from the horn of Africa to Libya and Europe. At the height of Europe's refugee crisis, Eritreans were one of the biggest groups from Africa arriving by sea. Thousands drowned. Others survived and in the 12 months up to September 2016, 30,705 made first time applications for asylum in the European Union. Many others, of course, don't get further than Ethiopia or Sudan.

‘They didn’t allow me to perform my work’

For Asmelash, a softly-spoken Eritrean actor, the UN’s findings confirmed what he knew already. Asmelash is 32 and has lived in the Adi Harush camp for more than a year. He recently began teaching drama classes to younger refugees, including Tesfay.

Born in Ethiopia, Asmelash was a child actor who appeared in TV commercials and films before the civil war. When the conflict ended 14-year-old Asmelash, his mother and two sisters, were deported to Eritrea during the mass displacement of people in 1998. ‘There was discrimination in Eritrea for us raised in Ethiopia,’ he said of life after the war. ‘They blame us for everything. If someone commits a crime, they blame us. The government wanted us to fight within our communities. They created a sort of hatred among us.’ Even so, Asmelash’s passion for acting grew and he continued to perform in films and plays, and eventually wrote his own scripts and directed films.

As a public figure who refused to actively praise the regime in every piece of work, he faced constant harassment. Then they locked him up. ‘I was arrested and held for two years without natural light in a basement,’ he said.

Looking over his shoulder was exhausting and he resented life in Eritrea. ‘It didn’t allow me to perform my work. If you don’t work for them they don’t like it,’ he said. ‘They have power, they could do anything. When they put you in prison, they don’t review it, they don’t follow legal proceedings. They just sentence you. All these things made me leave.’

Few people leave Eritrea to come to Europe. They come to Europe – and elsewhere – to flee their country.

Why Eritreans get stuck in Ethiopia

On arrival in Ethiopia, refugees initially feel relief, a sense of freedom and familiarity. Many have family in Ethiopia and welcome the chance to be reunited after years apart. But calm quickly becomes anxiety. Life in Ethiopia is difficult, particularly in Adi Harush, which is a refugee camp in a poor rural community where there are few economic opportunities even for informal labour.

‘I have the scars’

Asmelash tried to reach Europe three times before he gave up. His story is common among refugees living in Adi Harush. Captured by smugglers policing the routes to Europe, he was tortured in Libya, Egypt and Sudan. ‘I have the scars here,’ he said touching his thighs. ‘My relatives paid ransom for me many times. I don’t want to do this again.’ The debt accrued from kidnapping ransoms causes stress. Sometimes the debtors are too close. There is at least one that lives in Shire, the nearest major town.

‘Resettlement is a privilege not a right’

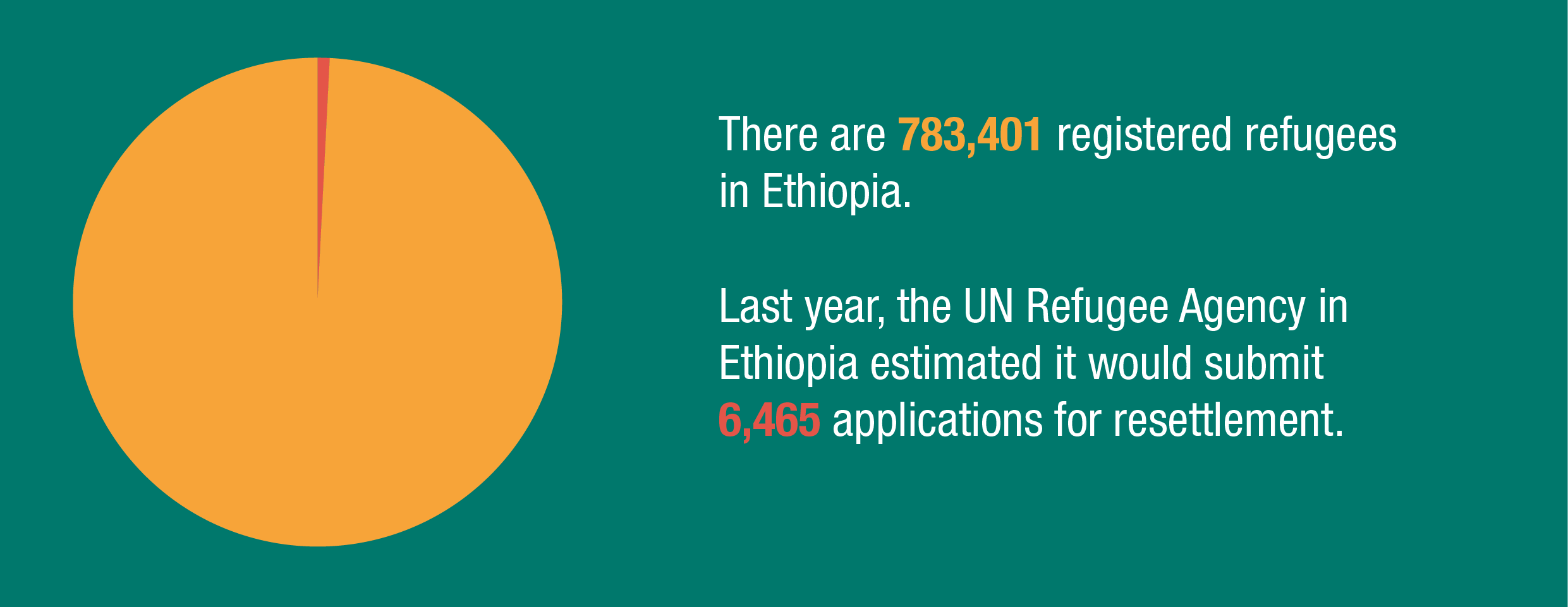

Everyone dreams of resettlement, but the odds are low. Last year UNHCR Ethiopia estimated it would submit 6,465 applications for resettlement, a tiny percentage of the nearly 800,000 refugees in the country.

Resettlement places are few, critera are stringent and the process is slow. Most submissions go to the US, which settles around 97% of resettlement submissions from Ethiopia. But resettlement can take years and is dependent on the speed in which receiving countries process applications. ‘Resettlement is a privilege not a right,’ said an aid worker working in Addis Ababa. ‘The quotas are small. The refugees wait for years and years, they are frustrated. So they take risky routes.’

Not everyone shuns the resettlement process. Sham Alem is 17 with a passion for art. He has lived in Adi Harush for five years. His work is displayed in the tidy brick hut he shares with his mother and three younger siblings; pride of place is a careful sketch of an elderly neighbour, the depth of her eyes and intricate patterns of her robes bought to life with a pencil.

Sham likes to paint scenes of the migration journey refugees take to Europe. Desert prisons, bodies stuffed into trucks and torture. Sham says these are based on warnings given to refugees in the camp by UNHCR officials and from ‘genuine stories’ of people he knows. ‘There was a woman with her son. She drowned while crossing the sea,’ he said. ‘In my opinion immigration is not good. The only solutions are, one, wait for the legal resettlement process. Otherwise, remain here and stay. Never undergo secondary movement.’

Sham Alem’s mother Azeb has applied to resettle the family to Canada. She received a confirmation letter three years ago, and has heard nothing since. The family left Eritrea when Azeb’s husband was jailed. ‘I have no idea why. He never abandoned his post, he never deserted the military. A year after he was in prison they stopped giving me ration cards.’

Azeb struggles to share her son’s optimism, partly because of her ill health. The 35-year-old once supplemented the family’s UNHCR rations by selling injera pancakes and beer, but stopped more than a year ago because of severe stomach ache and exhaustion. ‘Sometimes we feel hopeless about the resettlement country. There are rumours around the camp that Canada abandoned resettlement of refugees,’ she says. ‘I am really concerned about my children, not about me, I want them to have opportunities.’

Key recommendation: make resettlement process clear and transparent to help people manage their expectations and allow them to plan their future.