It is morning in Kibera, a neighbourhood about seven miles from the centre of Nairobi. Smartly dressed young children – white socks pulled up to their knees, school jumpers on and bags over their shoulders – will wave to their parents and set off for school. Among them is Purity, who walks for two hours a day along roads without sidewalks, inches from thundering trucks spewing thick diesel fumes.

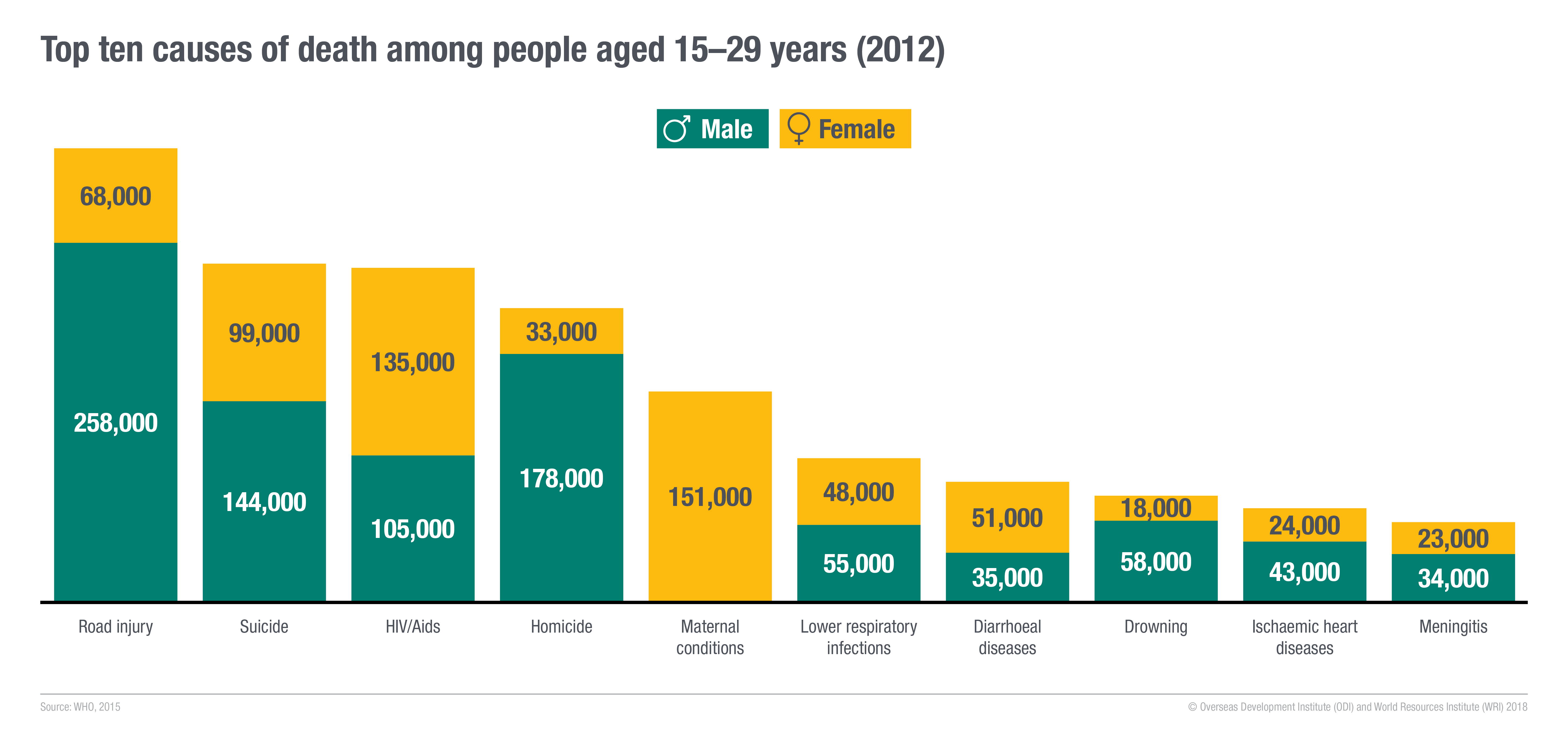

Road safety has been escalated to an issue of international concern but globally, numbers of fatalities are rising and it is now the biggest killer of young people worldwide.

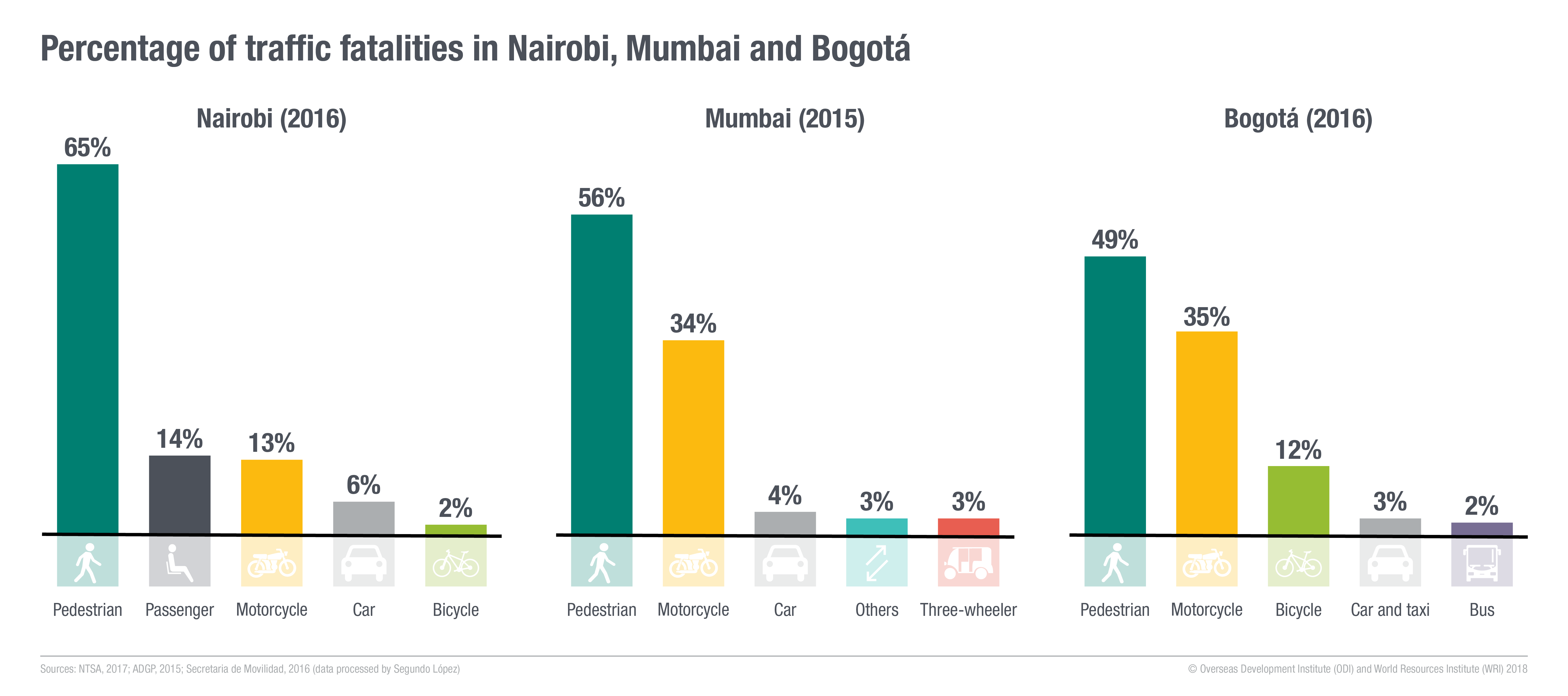

Purity is just one child in a city that is home to three million people. Twice a day, large numbers of school children join the thousands of commuters navigating fast roads, non-existent crossings, inattentive drivers and foul air. It’s little wonder that 65% of all road-related fatalities here are pedestrians.

Like any mother, Purity’s wants her daughter to do well in life – but her hopes for the future are tempered by more immediate concerns about the dangerous journey to school. ‘We fear when they are going out, when they are coming back,’ she says. ‘As my daughter is getting out and returning home I pray, “God, get me back my daughter.”’

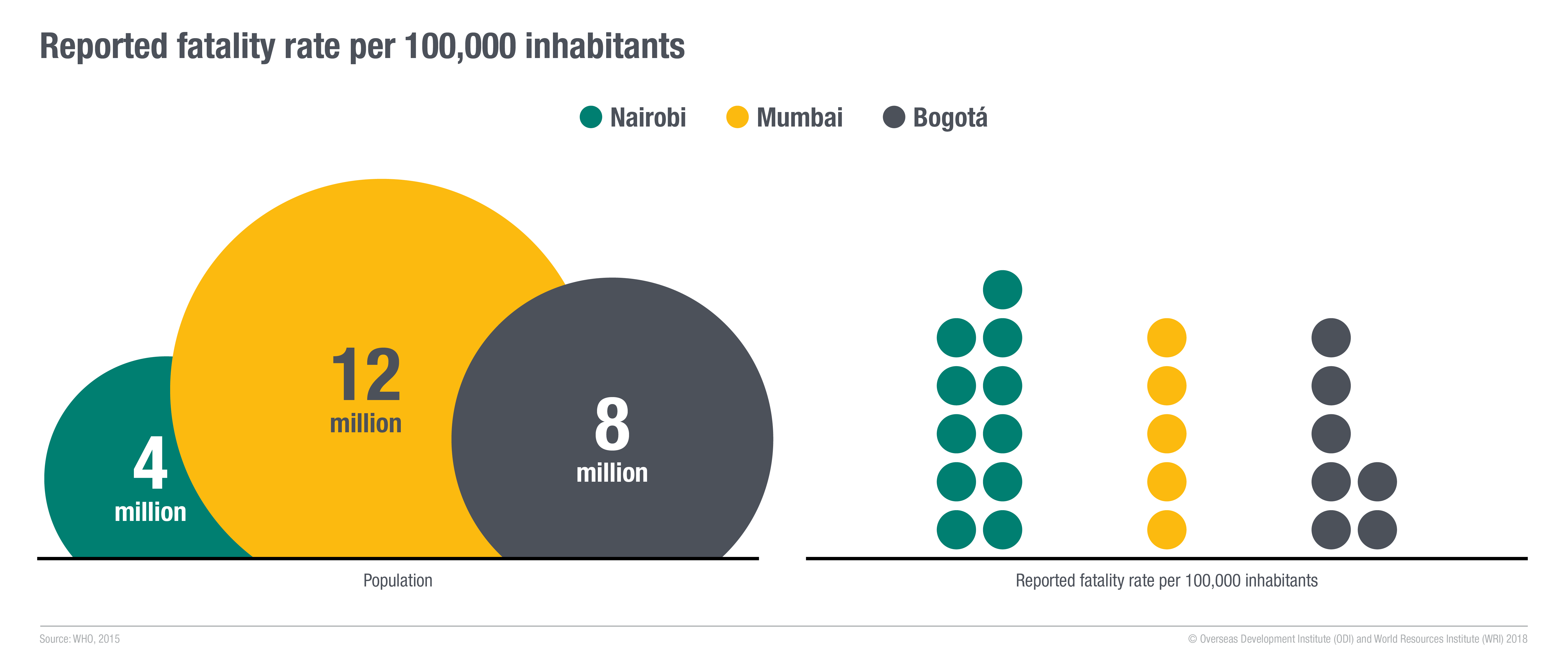

Around the world, each year, traffic collisions kill 1.25 million people and injure up to 50 million more. Road-related fatalities mainly occur among poorer, working-age males who walk or cycle around their city and town. School-age children also face disproportionately higher risks. Worldwide, 90% of fatalities occur in low- and middle-income countries – countries like Kenya, India and Colombia.

The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and the World Resources Institute (WRI) have undertaken a research project to identify the challenges to improving road safety in low- and middle-income countries, learn from stories of progress, and provide a series of strategies that can help decision makers and practitioners working on road safety reform.

Making our roads safe requires infrastructure, services and policy solutions. Public transport, cycle paths, sidewalks and crossings should be planned and built with the whole community in mind, not just drivers. And resources are needed for infrastructure and law enforcement.

But road safety is also political. In many cases decision-makers have the money, the data and the ability to make improvements but there is little demand or motivation.

The 'Safe System' approach

A study of 53 countries found that those that have taken a ‘Safe System’ approach to road safety have been able to reduce traffic fatalities faster and to a greater degree than other countries.The approach is based on a set of principles that experts and policymakers can use as a guide. They represent a shift in perception, away from road safety as a personal responsibility to a public health issue that governments have the responsibility and power to address.

Costs and consequences

For families and communities, the social and financial impacts of both fatalities and injuries are substantial. They are compounded for people living in poverty.

Traffic collisions burden already stretched healthcare systems and, particularly, those households left without a breadwinner. A serious injury might mean months of lost work and impaired mobility – consequences that hit the poor disproportionately hard. Children may suffer trauma and fall behind at school, making it harder for them to achieve their potential.

While the cost of road safety failings weighs most heavily on those directly affected, the financial cost to society is substantial. Road collisions have been quantified by the World Health Organization as costing 3% of global gross domestic product.

The four challenges of road safety

While there is knowledge about what to do and there are successful examples of how to do it, in many places progress is being made too slowly to keep up with the increasing number of pedestrians and cars on urban streets.

Avoiding fatalities is not just about building 'better' roads. Poor street design, limited safe public transport options, dangerously high vehicle speeds and inadequate enforcement of traffic laws are some of the many factors that contribute to an increased risk of collisions in today's fast-growing cities.

Road safety research has largely focused on technical aspects like urban planning and vehicle standards but we wanted to know why reforms are not being embraced. Findings from Nairobi, Mumbai and Bogotá helped us identify four key challenges facing those looking to address road safety:

- Expectation. Instead of blaming collisions on a lack of infrastructure, inadequate regulation, poor planning or unsafe vehicles, politicians and the public blame road users themselves.

- Fragmentation. Government bodies with responsibilities related to improving road safety are not coordinated.

- Prioritisation. Road safety isn’t seen as a politically rewarding topic. As such, it isn’t prioritised.

- Comprehension. There isn’t enough data to understand the nuances of the problem and this is used to excuse inaction.

These challenges help to encapsulate why road safety reforms make less progress in some places than in others: understanding and addressing them is critical to ongoing efforts to improve road safety.

Many low- and middle-income countries are facing similar issues to those faced by our case study cities. Our research makes recommendations to help city governments, local advocacy groups and international organisations more effectively overcome the challenges of road safety reform.

The way forward

Policy-makers tend to view road safety as a purely technical issue that can be easily addressed through improvements in infrastructure. But it is also a political issue. Reformers, whether they are in government, the private sector or civil society, must navigate the political case for reform. Of course, this makes the issue of road safety much more complex, encompassing equality, law and justice, health, economics, education and public attitudes. This may be daunting but it also reveals opportunities.

People will want reform for different reasons. This doesn’t matter. A business owner may want a bigger sidewalk outside their shop to encourage more business. Traffic management might be needed to ease congestion. Stakeholders might not view these issues as being explicitly about road safety, but wrapping road safety into them harnesses the energy surrounding issues that already have traction.

Opportunities exist at all levels. Whether power and money have been devolved to a city or not, whether local actors are able to drive or block reform, no one government system offers the best chance of progress on road safety. It is important to engage stakeholders at all levels of both government and society to build a coherent and holistic approach that spans departments and agencies.

An inclusive approach is essential. Progress has been slow in Nairobi and Mumbai, often due to the fragmentation of responsibilities across government departments. In Bogotá, however, a focus on reducing violent deaths led to a decrease in the number of road-related fatalities, while increased cross-institutional coordination and improved faith in institutions helped build the public case for reform.

But to make progress, don’t you need good data? Improvements in data collection and analysis can help to identify opportunities, coordinate stakeholders and engage the public. But progress shouldn’t be delayed because the data is incomplete. Basic investments in ‘good enough’ data – for example in locating crash hotspots – are enough make simple meaningful gains.

These entry points provide a way for reformers across government, the private sector and civil society to move forward, achieve the Sustainable Development Goals on road safety, and create a safer world for the billions of people who rely on our roads every day.

- Tackle road safety together with other agendas. Find road safety champions and align complementary road safety agendas, for example easing congestion, reducing pollution and increasing affordable efficient mass transit.

- Link road safety with other issues that people care about. Road safety touches on so many other issues: economics, equality, education, social inclusion, law and justice. In Bogotá progress on road safety was made when it was associated with civil society pressure to reduce violent deaths.

- Seek opportunities at all levels of government. Those looking to make progress on road safety must understand and respond to the political and institutional dynamics at play in their cities and countries: find the actors with the power to drive reform, or block it.

- Take advantage of wider institutional and governance reform. Reforms to the police, public transport, city finances and transport department can create opportunities to push road safety issues, mobilise resources and galvanise support.

- Sequence actions. Rather than reaching for one integrated, simultaneously delivered solution that may face resistance, develop a plan to coordinate and prioritise actions over the short, medium and long term; taking into account the degree of impact as well as the political and financial feasibility.

- Don’t wait for perfect data. Basic investments in ‘good enough’ data are enough to identify the most urgent road safety needs and inform the public about them.

Sustainable Development Goal 3 includes a pledge to halve the number of fatalities and injuries from traffic collisions by 2020 and, over the last 10 years, a range of international agencies have prioritised the issue. It looks unlikely that the goal will be met.

We need action now.